Chapter 126

Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

Neurogenic

Jason T. Lee

Based on a chapter in the seventh edition by Robert W. Thompson and Matt Driskill

An increasing body of experience demonstrates that excellent outcomes can be achieved by a comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach to neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (nTOS), including a prominent role for surgical treatment in well-selected patients, particularly when well-defined algorithms are employed.1–4 Nonetheless, uncertainties in diagnosis and disappointing results of treatment have led some authorities to question the need for surgical management of nTOS and even to challenge whether the condition actually exists.5–8 The purpose of this chapter is to review current understanding of the evaluation and diagnosis, optimal management and adjunctive techniques, and surgical techniques for nTOS. The anatomy of the thoracic outlet region for the vascular (arterial and venous) or neurogenic forms of TOS is similar (see Chapter 125). For evaluation and diagnosis in patients with nTOS, this chapter will discuss physical therapy, scalene injections, and surgical predictors of success and will focus on quality-of-life (QOL) outcomes as an important reporting standard. In terms of surgical technique, this chapter will focus on the transaxillary approach, discuss pectoralis minor syndrome, and address postoperative complications or lack of success after surgery for nTOS. Note that the supraclavicular approach to surgery is described in Chapter 127.

Etiology

Current wisdom asserts that nTOS is caused by a combination of predisposing anatomic factors and previous neck trauma that bring attention to the region of discomfort. Indeed, the normal anatomy of the thoracic outlet serves as a predisposing factor for the development of nTOS because the neurovascular structures that traverse this region are prone to compression even during the course of regular daily activity. Activities involving sustained or repeated elevation of the arm or vigorous turning of the neck may place additional tension on the scalene muscles, thereby potentiating any positional compression of the underlying nerve roots. Such activities are often seen in athletes, laborers, office workers who remain in certain positions for extended periods of time, and individuals who have had a recent whiplash-type car accident. This anatomic predisposition may be further increased by congenital structural variants such as scalene muscle variations, abnormal tendinous bands, or cervical rib anomalies. However, because many individuals harbor such variations in the absence of neurogenic symptoms, anatomic factors are considered a predisposing factor for nTOS rather than a distinct and separate cause, and they appear only to lower the threshold for the development of symptoms after injury or repetitive motions.

Neck Trauma

Most patients with nTOS will recall some form of previous trauma to the head, neck, or upper extremity, followed by a variable interval before the onset of progressive upper extremity symptoms.1,8 The interval between injury and the onset of symptoms may range from days and weeks to several years. This frequent delay in symptoms is thought to reflect the variable time frame for scalene muscle injury to result in sustained compression and irritation of the brachial plexus nerve roots and may therefore obscure the relationship between a specific injury and the development of nTOS. Unfortunately, this vague delay also often introduces some question in the referring physician’s minds regarding the legitimacy of the patients’ complaints, further delaying referral to the nTOS expert. In some patients the inciting injury has been long forgotten, and a history of trauma may be overlooked if not specifically sought by the examining physician. Persistent use of the upper extremity in activities that promote brachial plexus compression may further exacerbate progression of symptoms over time and result in progressive disability, and many patients do not seek medical attention until the symptoms are well advanced. Thus it is important to recognize that low-grade repetitive trauma can also contribute to this disorder.

Repetitive Strain Injury

Over the past several decades, it has become increasingly evident that not all patients with nTOS have their condition brought on by a specific traumatic event. In many cases, the injury may be the result of repetitive activities that inadvertently place strain on the scalene muscles over long periods, such as prolonged work at computer keyboards or sports involving the upper extremities (baseball, football, swimming, rowing). TOS occurring in these circumstances is considered to be a form of repetitive strain injury. Another contributor in athletes may be particularly bulky scalene muscles that are out of proportion to the upper torso frame. Athletes that undergo operation for ntOS seem to have a particularly high success rate after operation.4 In these repetitive strain injuries, it is also possible that age-related changes in posture (e.g., slumping of the shoulders, stooping of the neck) superimposed on congenital or work-acquired variations of the scalene musculature may be significant factors leading to the development of extrinsic neural compression.

Pathophysiology

nTOS is thought to develop as a result of scalene muscle repetitive trauma, the pathophysiologic response to muscle injury, and anatomic factors predisposing to compression of the brachial plexus nerve roots as they pass through the scalene triangle. Hyperextension injury of the anterior scalene muscle probably leads to acute and chronic inflammation and a reparative process that includes fibrosis and persistent muscle spasm. Chronic changes in the scalene musculature also include fibrotic contracture and stiffening, as well as histopathologic alterations reflecting persistent muscle injury. The resulting changes in the scalene muscles probably potentiate nerve root compression and irritation, which may be exacerbated by positional effects and lead to progression of symptoms over time. Intermittent exacerbation of neurogenic symptoms may occur as a result of additional scalene muscle injury that produces local inflammation and spasm, interspersed with periods in which symptoms are quiescent. Unfortunately, knowledge of the specific pathophysiologic mechanisms leading to nTOS is limited, and there remain many scientific gaps in our understanding of this complicated disorder.

Histopathology

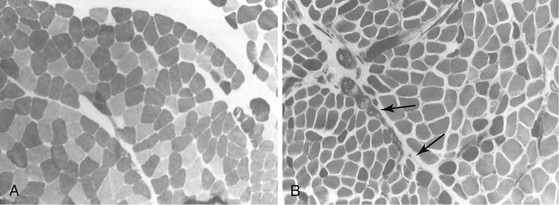

Microscopic studies of scalene muscles from patients with nTOS have consistently revealed two major abnormalities: (1) predominance of type I muscle fibers and (2) endomysial fibrosis (Fig. 126-1).9,10 Although the anterior scalene muscle normally has an equal distribution of type I (“slow-twitch”) and type II (“fast-twitch”) muscle fibers, in patients with nTOS, up to 78% of the scalene muscle fibers are type I, with type II fibers exhibiting atrophy and pleomorphism. Along with these changes is marked thickening of the connective tissue matrix that surrounds individual muscle fibers and a twofold increase in connective tissue content in comparison with normal scalene muscles; in some cases, mitochondrial abnormalities resembling those seen in muscular dystrophy are also present. Because biopsy of unaffected muscles in patients with nTOS fails to reveal similar abnormalities, these changes do not represent a general myopathy but only a local abnormality. These findings are therefore thought to reflect the histopathologic changes occurring after long-standing muscle injury, sustained muscle spasm, and abnormal tissue remodeling, most likely resulting from previous trauma to the scalene muscles. These observations are therefore consistent with the frequent history of neck trauma and repetitive injury in patients with nTOS.

Figure 126-1 Scalene muscle histopathology showing changes consistently observed in neurogenic thoracic outlet syndrome (nTOS). Sections of the anterior scalene muscle were stained with myosin ATPase (pH 9.4) to visualize the fiber types, with type I fibers staining lightly and type II fibers staining dark (original magnification ×100). A, Normal muscle has an equal distribution of type I and type II fibers. B, Muscle from a patient with nTOS exhibits predominance of type I fibers, atrophy of type II fibers, and a significant increase in the connective tissue matrix between fibers (arrows). (Redrawn from Sanders RJ: Thoracic outlet syndrome: a common sequela of neck injuries, Philadelphia, Pa, 1991, JB Lippincott.)

Clinical Findings

The diagnosis of nTOS rests largely on recognition of clinical patterns and presentations, with diagnostic suspicion raised by a stereotypical history and a description of symptoms characteristic of the disorder. Patients covered by workers’ compensation are often diagnosed with so-called cervicobrachial syndrome, a nondescript moniker used by evaluators when the diagnosis is uncertain. The provisional diagnosis of nTOS is supplemented by certain physical examination and may be supported by a limited number of diagnostic studies. In most cases such studies are of value primarily in the exclusion of other (more common) orthopedic conditions within the differential diagnosis because no single diagnostic test has a sufficiently high degree of specificity to completely prove or exclude the diagnosis of nTOS.8,11

Symptoms

Demographics

nTOS most frequently occurs in individuals between 20 and 40 years of age, and approximately 70% of affected patients are women. nTOS may arise in individuals engaged in a variety of occupational or recreational activities, most often those involving repeated use of the arm or arms in elevated positions or after a spectrum of injuries to the head, neck, or upper extremity. nTOS may also develop in patients with no apparent predisposition (i.e., no anatomic variations or history of trauma). There are no medical conditions or known inherited patterns predisposing to nTOS. High-performance athletes engaged in baseball, football, volleyball, swimming, and rowing represent a growing number of patients who will present most demonstratively with venous TOS but who can have mixed signs of nTOS.12,13

Pain and Paresthesia

The primary symptoms of nTOS include extremity pain, dysesthesia, numbness, neck symptoms, weakness, and swelling.4 These symptoms usually occur throughout the affected hand or arm without any localization to a specific peripheral nerve distribution, and they often involve different areas of the entire upper extremity. Extension of symptoms from the hand to the shoulder, neck, jawline, and upper part of the back is not infrequent, and in many patients the symptoms in the neck or upper part of the back may be perceived as the most functionally disabling and most constant. Although most patients with nTOS have symptoms affecting just one upper extremity, bilateral symptoms are not uncommon; in such cases, the dominant extremity is often more symptomatic at initial evaluation, but the opposite extremity may become involved over time, perhaps as a result of compensatory overuse. The lack of distribution of symptoms into patterns referable to a single peripheral nerve and the frequent extension of symptoms to the shoulder, neck, and back allow distinction of nTOS from more reliably treatable nerve compression disorders affecting the ulnar nerve at the elbow (cubital compression syndrome), the median nerve at the wrist (carpal tunnel syndrome), or other related conditions. Different symptomatic manifestations of nTOS may be observed, depending on the brachial plexus nerve roots that are principally involved: upper plexus disorders (nerve roots C5, C6, C7) are dominated by symptoms in the distribution of the radial and musculocutaneous nerves, whereas lower plexus disorders (nerve roots C7, C8, T1) most commonly involve the median and ulnar nerves, and often these patients will point to their inner upper arm as to where the pain seems to radiate downward. In many cases, however, it is not possible to draw these distinctions because of a wider distribution of symptoms.

Positional Effects

Almost all patients affected by nTOS describe reproducible exacerbation of symptoms by activities that require elevation or sustained use of the arms or hands. These activities may include simply reaching for objects overhead, lifting, prolonged typing or work at computer consoles, driving a motor vehicle, speaking on the telephone, shaving, and combing or brushing the hair. Positional effects may also be brought on by lying supine, especially when the arms are positioned overhead, and can result in pain and difficulty sleeping at night. Documentation at baseline of activities of daily living and the inability to perform certain routine household chores, work activities, or recreational efforts is one of the more recent advances in the literature related to nTOS.4,14 This clear documentation by QOL outcomes surveys allows surgeons to more accurately document postoperative improvement, or lack thereof, and is particularly helpful when reviewing a surgeon’s outcomes.

Weakness and Muscle Atrophy

Prolonged, severe extrinsic compression of peripheral nerves can result in muscle weakness and atrophy, but such findings occur much less than the pain and paresthesias that most patients will describe. This lack of atrophy is probably because of the intermittent nature of nerve compression in nTOS, which produces pain and other neural symptoms but prevents permanent motor nerve dysfunction. Most commonly, hand or arm pain with use of the affected extremity may lead to the perception of weakness and cause the patient to avoid use of the arm or positions that exacerbate symptoms; this distinction should be sought during evaluation to help identify other conditions that may be responsible for the symptoms of muscle weakness. Many times the athletes that present for possible nTOS have noted a dropoff in performance and report the inability to push the arm to extreme limits in endurance activities. The presence of authentic muscle weakness may therefore indicate particularly severe and long-standing compression of the brachial plexus nerve roots as a result of nTOS or another condition. Obvious atrophy is also seen when a cervical rib is present and the brachial plexus roots have been severely distorted in the scalene triangle.

Disability

The majority of individuals with positional complaints related to nTOS are affected to only a mild and tolerable degree. These symptoms are usually due to transient irritation of the brachial plexus with certain positions of the arm or during certain activities, and to some extent, such symptoms are frequent in the normal population. Little risk of progressive injury exists in these situations, and no specific intervention is warranted. Patients inquiring whether their arm discomfort or disability will lead to permanent damage can usually be reassured that with positional exercises, avoidance of certain activities, and good physical therapy, it is unlikely they will progress to severe permanent disability.

However, a smaller number of patients with clinically significant nTOS will exhibit progressively disabling symptoms that effectively prevent them from working, playing, or carrying out simple daily activities. These patients often describe progressive disability and a long history of consultations with different physicians and partial or ineffective treatments. By the time nTOS is considered, many patients have seen physical therapists, orthopedists, physiatrists, chiropractors, and spine surgeons. Such patients may have been prevented from working for a long time before consultation or may have attempted to persist in work-related activities despite ongoing neurogenic symptoms. Part of the initial assessment of a patient with nTOS is therefore concerned with assessing the extent of the patient’s disability and expectations for the potential to continue or return to work. It is particularly helpful in this regard to obtain a detailed description from the patient of activities that exacerbate the symptoms associated with nTOS, as well as activities normally required in the workplace. Documentation of this assessment is often important if restrictions from work are necessary in the management of these patients and in guiding decisions about the role of surgical treatment. One such instrument described and validated in the literature is the QuickDASH (QD) questionnaire (DASH = disability of the arm, shoulder and hand).4,14–16 This survey for disorders of the upper extremities has been extensively validated in orthopedic and hand surgery literature; recently, it has been increasingly used in nTOS outcomes reports. The QD instrument uses 11 items to objectively measure physical function and symptoms in people with any single or multiple musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Scores range from 0 points (asymptomatic) to 100 (totally incapacitated). More information is available online (http://www.dash.iwh.on.ca/).

Arterial Symptoms and Complex Regional Pain Syndrome

Vascular symptoms, especially those ischemic in nature, should be specifically sought in the history of patients with suspected nTOS, particularly discoloration or coldness in the hands and fingers. It is important to note that ischemia is actually very unusual in such patients, whereas symptoms of vasomotor disturbance are not uncommon in those with long-standing or severe nTOS. Indeed, in some patients, the symptoms of TOS may have progressed to resemble those of complex regional pain syndrome type I (CRPS-I; formerly known as reflex sympathetic dystrophy [RSD]), characterized by persistent vasospasm, disuse edema, and extreme hypersensitivity. The acuity of these symptoms often leads to avoidance and withdrawal from even light touch of the affected extremity. The diagnosis of CRPS-I can be supported by vascular laboratory studies revealing abnormal vasoconstrictive responses (cold pressor tests) or imaging studies of the hand microcirculation, but in most cases the diagnosis is made on clinical grounds. Identification of this condition in patients with nTOS is important because it may lead to an earlier recommendation for operative treatment and consideration of concomitant cervical sympathectomy.

When a history suggesting arterial insufficiency or thromboembolism exists, vascular laboratory studies and cross-sectional imaging with contrast or extremity arteriography may be necessary to exclude the presence of subclavian artery aneurysm or occlusive disease. Remember that solely relying on contrast arteriography will illustrate only the arterial lumen and could miss a subtle subclavian aneurysm or poststenotic dilatation that contains thrombus. Conversely, a history of arm swelling, cyanotic discoloration, and distended subcutaneous collaterals may indicate venous TOS secondary to obstruction of the subclavian vein, which may require venography for full evaluation. Identification of these conditions in patients with nTOS is vital because the coexistence of neurogenic and vascular forms of TOS will have an impact on the decisions and plans for surgical treatment.

Physical Examination

Physical examination is initially directed toward eliciting the degree of neurogenic disability and identifying particular factors that exacerbate painful hand and arm complaints. The range of motion of the upper extremity and lateral motion of the neck are assessed under both passive and active conditions. Pain and tenderness over the shoulder joint are evaluated as potentially being related to rotator cuff pathology, and tenderness over the trapezius muscle may indicate fibromyalgia. A thorough peripheral nerve examination is performed to exclude ulnar nerve entrapment or carpal tunnel syndrome, two conditions that may mimic the symptoms of nTOS. The base of the neck is examined to identify the extent of any local muscle spasm over the scalene triangle itself, as well as over the trapezius, pectoralis, and parascapular muscles, and to localize specific areas that reproduce the individual patient’s symptom pattern on focal digital compression. The presence of “trigger points” is sought to identify specific sites where palpation recreates the patient’s typical symptoms of upper extremity pain and paresthesia. Localization of such trigger points over the scalene triangle serves to strongly reenforce the diagnosis of nTOS.

Perhaps the most useful component of physical examination is the 3-minute elevated arm stress test (EAST), in which the patient is positioned with the arms elevated in a “surrender” position and asked to open and close the fists repetitively. Most patients with nTOS report a rapid onset of their typical upper extremity symptoms with EAST and are often unable to complete the exercise beyond 30 to 60 seconds. When there is no difficulty performing the 3-minute EAST, the diagnosis of nTOS is in doubt and an alternative explanation for the symptoms should be sought more vigorously.

In some patients, compression of the neurovascular bundle as it passes underneath the pectoralis minor muscle tendon is a substantial factor contributing to nTOS. This situation is sometimes described as the “hyperabduction syndrome” or the “pectoralis minor syndrome” and is identified by localized tenderness and reproduction of the upper extremity neurologic symptoms on palpation over the pectoralis minor muscle. Given that pectoralis minor tenotomy may be an effective primary or adjunctive treatment in such individuals, it is important during the initial physical examination to identify this increasingly recognized component of nTOS.

Vascular Examination

The Adson maneuver is commonly used to identify positional compression of the subclavian artery by detecting ablation of the radial pulse when the patient inspires deeply and turns the neck away from the affected extremity, with or without elevation of the arm (see Chapters 125 and 127) Although this maneuver does not specifically reveal nerve root compression, positive findings may be associated with nTOS.4 It is important to recognize that a positive Adson sign is also common in the asymptomatic general population. This maneuver may therefore serve to support but not prove the diagnosis of nTOS. It is equally important to recognize that negative findings of arterial compression do not exclude a diagnosis of nTOS. Most physicians experienced with TOS therefore find the Adson test to be of little specific value; however, documentation of this test and its findings can aid in the explanation to the patient of abnormal findings with odd symptoms.

Patients with symptoms of nTOS may on occasion have vascular findings related to either arterial or venous TOS. It is important that these conditions be identified early in the evaluation because their presence may lead to specific tests and modified treatment recommendations. During physical examination, the surgeon should seek evidence of arterial compromise to the upper extremity, such as sympathetic overactivity with vasospasm, digital or hand ischemia, cutaneous ulceration or emboli, forearm claudication, or the pulsatile supraclavicular mass or bruit characteristic of a subclavian artery aneurysm. Comparison of blood pressure in each arm is also valuable to identify any evidence of arterial occlusion. Venous TOS, in contrast, may be associated with hand and arm edema, cyanosis, enlarged subcutaneous collateral veins, and early forearm fatigue in the absence of arterial compromise.

Diagnostic Tests

A wide variety of diagnostic tests and imaging studies are used for the evaluation of patients with nTOS, and most patients have had a number of such studies before consultation with the vascular surgeon. The results of specific diagnostic tests are negative or equivocal in most cases of nTOS, and no specific diagnostic test or imaging study can replace the clinical diagnosis of this condition. Thus the principal value of the studies described in the following sections is to exclude other conditions, thereby helping strengthen the diagnosis of nTOS.

Radiography

Plain radiographs of the neck are helpful in determining whether an osseous cervical rib or an abnormally wide transverse process of the cervical vertebrae is present. Although each of these findings may solidify the diagnostic impression of TOS, neither of them is essential. Still, finding patients with cervical ribs who present with signs and symptoms consistent with nTOS is important, because that patient cohort often benefits significantly from operative intervention.17

Cross-Sectional Imaging

The results of computed tomography, MRI, and other imaging examinations are usually negative in nTOS because the anatomic factors leading to intermittent or positional nerve compression are generally beyond the resolution of these studies. Even in situations in which an apparent imaging abnormality exists in the region of the scalene triangle, it is usually impossible to prove the functional importance of such abnormalities with respect to the patient’s upper extremity complaints. Imaging studies are nonetheless important to exclude other conditions that could be responsible for the upper extremity symptoms, such as degenerative cervical disk or spine disease, shoulder joint pathology, or various forms of intracranial pathology.

In recent years, advances in MRI and data processing have led to higher resolution scans with three-dimensional reconstruction, along with the ability to detect localized abnormalities in nerve function (MR “neurography”).18,19 As this technique becomes used more frequently in patients with and without nTOS, it may provide an improved diagnostic tool to supplement clinical evaluation with an accurate “objective” test for this challenging problem. There remains a need, however, for better studies to document the predictive factors of these MRIs for nTOS and whether they make a difference in the operative approach or selection of these patients. A more challenging scenario occurs when a patient presents with expectations of surgery based on high-resolution MRI results that say “positive” for compression of the brachial plexus. As will be described later, having an algorithmic approach to patient selection will help with standardizing one’s practice and likely improve patient expectations and outcomes.

Neurophysiologic Testing

Electromyography (EMG) and nerve conduction studies (NCS) are often used early in the evaluation of patients suspected of having nTOS, particularly when the symptoms are suggestive of a specific radiculopathy, a peripheral nerve syndrome, or a general myopathy. Positive results of neurophysiologic testing are therefore useful in that they point to specific conditions that must be evaluated further. Unfortunately, the results of conventional EMG/NCS are usually negative in nTOS because the nerve root compression occurs in a proximal location, is intermittent, and is not typically associated with permanent changes in motor nerve function.20 Negative results from these studies are nonetheless valuable in the diagnostic evaluation of some patients by excluding other conditions from further consideration. Positive EMG/NCS findings in patients with suspected nTOS are a poor prognostic sign in the absence of an alternative explanation because they indicate an advanced stage of neural damage that may be unlikely to resolve despite adequate decompression. Recent evidence suggests that electrophysiologic testing of sensory nerve abnormalities may be more useful in the diagnosis of nTOS than conventional EMG/NCS. For example, Machanic et al compared the response with medial antebrachial cutaneous nerve and C8 nerve root stimulation in 41 patients with a clinical diagnosis of nTOS and in 19 asymptomatic controls; they reported that electrophysiologic testing had a high degree of sensitivity and specificity.21

Scalene Muscle Blocks

Injection of local anesthetic into the anterior scalene muscle has been popularized by the UCLA group as an adjunct to the clinical diagnosis of nTOS, particularly in predicting the potential response to surgical decompression.22 A successful scalene muscle block is indicated by relief of symptoms in the hand or arm, along with a reduction in local tenderness over the anterior scalene muscle. Injection of anesthetic to the level of the brachial plexus precludes accurate interpretation of this test because the temporary numbness and weakness in the arm will make assessment of pain relief unreliable. Although scalene muscle block is not necessary in patients with clear-cut symptoms in whom the diagnosis is not questioned, it is most useful in patients with an equivocal diagnosis of nTOS. In the most recent report from the Hopkins group, Lum and colleagues23 found success rates in the 67% to 90% range in patients operated on for nTOS who responded to lidocaine blocks, and particular improvement when using this as a distinguishing factor in patients over 40 years old. A variation of scalene muscle block as a treatment of nTOS that showed promising early results but has not been consistently reported in the literature is the use of locally injected botulinum toxin.24,25 However, side effects of botulinum toxin may occur early after treatment (e.g., dysphagia), the duration of beneficial effects with botulinum toxin is often limited to 3 to 6 months, and the effects of repeated treatment are diminished by the systemic immune response to the injected protein. Thus in the absence of further studies, this approach cannot yet be generally recommended.

Angiography and Vascular Laboratory Studies

Vascular laboratory studies and angiography are not usually necessary in making the diagnosis of nTOS. However, patients with clinical features that suggest an arterial component of their disorder should undergo positional noninvasive vascular laboratory studies consisting of measurement of segmental arterial pressure, waveform analysis, and duplex imaging; furthermore, contrast-enhanced arteriography may be necessary to completely exclude or prove the existence of a fixed arterial lesion. Similarly, patients in whom venous TOS is suspected should be studied by duplex ultrasound, and in those who have a negative duplex study but in whom the clinical findings remain suspicious for venous TOS, contrast-enhanced venography should be performed if not done previously in the context of an “effort thrombosis” event. In each case, it is important to specifically seek out positional maneuvers during the performance of these diagnostic tests and to consider bilateral studies if any suggestion of contralateral symptoms exists.

Making the Diagnosis

Most patients suspected of having nTOS who consult a vascular surgeon have been referred to help resolve a diagnostic dilemma or to “rule out TOS,” especially when previous tests and consultations have resulted in uncertainty and a long list of conditions have already been considered in the diagnostic evaluation (Table 126-1). Although some of these entities can be distinguished by specific findings or tests, one is often left with a diagnosis of exclusion. An experienced surgeon evaluating nTOS should not be dissuaded by the impression that these problems are frequently associated with psychiatric overtones, dependency on pain medications, and ongoing litigation. Many patients with nTOS who can benefit greatly from proper intervention have suffered a progressively disabling condition at a relatively young age, without the satisfaction of diagnostic certainty or a reliable sense of prognosis. Careful evaluation can usually detect patients with strong clinical evidence of nTOS, as well as identify those most likely to respond to treatment.4 The evaluating surgeon must therefore be willing to expend considerable time and energy and paperwork to provide these patients with a thorough evaluation, detailed information, lengthy discussion, and ongoing support. Contact with prior patients who successfully underwent treatment is often a good way to provide some of the emotional support that is necessary when treating patients for pain syndromes. The suspected nature of the condition is explained, the diagnostic and therapeutic uncertainties that surround nTOS are discussed, and an honest but reassuring outline of treatment expectations is presented. Surgeons making this effort are typically rewarded by grateful patients with renewed hope for long-awaited improvement.

Table 126-1

Differential Diagnosis of Neurogenic Thoracic Outlet Syndrome

| Condition | Differentiating Features |

| Carpal tunnel syndrome | Hand pain and paresthesias in the median nerve distribution, positive findings on nerve conduction studies |

| Ulnar nerve compression | Hand pain and paresthesias in the ulnar nerve distribution, positive findings on nerve conduction studies |

| Rotator cuff tendinitis | Localized pain and tenderness over the biceps tendon and shoulder pain on abduction; positive findings on MRI; relief from NSAIDs, local steroid injections, or arthroscopic surgery |

| Cervical spine strain/sprain | Posttraumatic neck pain and stiffness localized posteriorly along the cervical spine, paraspinal tenderness, relief with conservative measures over a period of weeks to months |

| Fibromyositis | Posttraumatic inflammation of the trapezius and parascapular muscles; tenderness, spasm, and palpable nodules over affected muscles; may coexist with TOS and persist after surgery |

| Cervical disk disease | Neck pain and stiffness, arm weakness, and paresthesias involving the thumb and index finger (C5-C6 disk); improvement in symptoms with arm elevation; positive findings on CT or MRI |

| Cervical arthritis | Neck pain and stiffness, arm or hand paresthesias infrequent, degenerative rather than posttraumatic, positive findings on spine radiographs |

| Brachial plexus injury | Caused by direct injury or stretch; arm pain and weakness, hand paresthesias; symptoms constant, not intermittent or positional; positive findings on neurophysiologic studies |

CT, Computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; TOS, thoracic outlet syndrome.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree