Fig. 15.1

Anatomical illustration of the origin, course, and termination of the thoracic duct (Reproduced with permission from Stranding et al. [20])

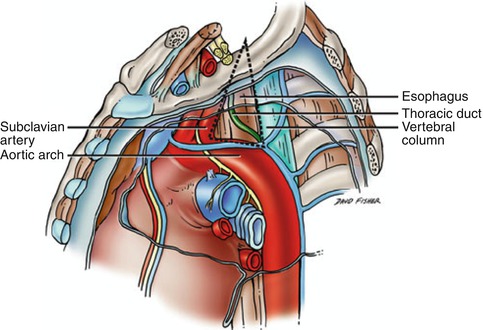

Fig. 15.2

Poirier’s triangle (dotted line) bounded by the left subclavian artery, vertebral column, and arch of the aorta (Reproduced with permission from Tubbs et al. [21])

15.2 Background/Incidence/Epidemiology

Lymphatic vessels are thin and easily damaged; however, clinical manifestations are generally only seen when disruption of the major ducts occurs resulting in chylous pseudocysts, fistulae, or chylous effusions of the thoracic cavity (chylothorax), pericardium, or peritoneum (chylous ascites). Loss of the protein and immune cell rich fluid caused by large volume of chyle leaks can result in malnutrition and immunosuppression. Without proper management, this loss of chyle can also cause dehydration, severe electrolyte abnormalities, and pulmonary insufficiency. Prior to the development of total parenteral nutrition (TPN) and surgical treatment of thoracic duct injuries mortality rates for thoracic duct leaks could approach 50 % [2, 5, 6].

Because of its location, protected by the spine, aorta, and mediastinum, injury to the thoracic duct is rare. When it does occur the most common causes of injury are iatrogenic during surgical procedures or, less commonly, due to traumatic injury [1, 7]. Iatrogenic injury to the thoracic duct occurs most commonly with neck or thoracic procedures, including central venous line placement, complicating between 0.37 and 2 % of thoracic procedures and up to 1–5 % of esophagectomies [2, 7–9]. Traumatic thoracic duct injury is rare, accounting for only 3 % of chylothoraces, and occurring in only 0.9 % of cases following penetrating neck trauma [9–11]. When due to penetrating trauma, it is often found in conjunction with visceral or vascular injuries. Isolated thoracic duct injuries occur in only 0.06 % of all penetrating neck and chest trauma [6]. Injury to the thoracic duct following blunt trauma is also very rare and is thought to be due most commonly to overstretching and rupture of the duct across the thoracic spine during hyperextension or by direct laceration by broken bones or osteophytes [2, 7, 12–14].

15.3 Clinical Assessment

As with all traumas, patients suspected of having a thoracic duct injury following blunt or penetrating trauma should be evaluated in a systematic fashion. Problems of airway, breathing, and circulation, as well as neurological deficits, should be identified and treated according to Advanced Trauma Life Support Protocols. Those with hard signs of vascular or aerodigestive injury such as pulsatile hemorrhage, lack of distal pulses, expanding hematoma, or air or saliva bubbling through open wounds should be taken to the operating room immediately for appropriate surgical exploration. Patients with effusions, pneumothoraces, or tension physiology should have tube thoracostomies placed. Once associated life-threatening injuries have been identified and addressed, thoracic duct injuries primarily present in one of two ways, either through manifestation of a chylothorax or during operative exploration. Less commonly, chyle fistula via the wound tract or chyle pseudocyst formation can be seen following penetrating trauma to the neck or chest.

The location of the thoracic duct injury will have a great deal of influence on how the injury manifests (Fig. 15.2). Injuries located high in the neck are often found with associated injuries and are commonly diagnosed when chyle is seen in the surgical field during neck exploration. When injured in the chest, thoracic duct injuries primarily manifest with chylothorax formation. Chylothorax presents most commonly with asymptomatic opacity found on chest x-ray, when symptoms are present they can include shortness of breath, chest pain, or cough. When injured high in the chest, most commonly within Poirier’s triangle, the space bounded by the left subclavian artery, vertebral column, and arch of the aorta, the injury presents with a left sided chylothorax [6]. Whereas injuries lower in the duct, below the cross over at the fifth thoracic vertebra, will result in right sided chylous effusions. Initial chest tube drainage may demonstrate the classical milky white drainage; however, fluid may initially be serous, serosanguinous, or bloody. There are several reasons for delay in obvious chylothorax: blood from associated injuries may mask the chyle leak, the duct injury may be small and chyle leakage may be slow requiring time to manifest clinically, and patients may be in a fasting state causing the chyle to be more serous in appearance. Typically chylothorax will manifest within 1–7 days of the initial injury [2, 6].

15.4 Diagnostic Testing

If there is concern for thoracic duct injury due to milky drainage from a thoracostomy tube, there are several options to confirm the presence of chyle. First, the fluid can be sent for triglyceride levels, if levels are greater than 110 mg/dL this is diagnostic for chyle leak, if less than 50 mg/dL the chances of chyle leak are less than 5 % and thoracic duct injury can effectively be ruled out [3]. For patients with triglyceride levels between 50 and 110 mg/dL, lipoprotein analysis or light microscopy can be used to detect chylomicrons confirming the presence of chyle, alternatively Sudan III stain can be used to confirm the presence of fat globules [2]. Additionally, the clinician can perform a cell count, chyle will demonstrate a predominance of lymphocytes (>90 %) or if the patient is on a diet cream can be administered and the drainage observed for change in character. Administration of milk or cream is also useful preoperatively for identification of the injury and localization for duct ligation.

More invasive methods of identifying and, more importantly, localizing thoracic duct injury include lymphangiography where diffusible blue dye is injected into the interdigital web spaces and lymphoscintigraphy with similar injection of a radiotracer and serial scanning (Fig. 15.3) [1, 2]. However, both of these methods are invasive and can be painful and poorly tolerated by patients and either technique may not be available in all hospitals.

Fig. 15.3

Radiographic image showing extravasation of the contrast in the upper part of the thoracic duct (arrow), following injection of the duct with iodinated contrast through the microcatheter (Reproduced with permission from Itkin et al. [8])

15.5 Initial Management and Outcomes

Initial management of thoracic duct injury depends upon presentation and volume of the leak. In patients in whom the injury has been identified intraoperatively, maneuvers should be taken to localize the injury, such as the administration of cream or absorbable dye. Once the injury is localized, the duct should be ligated proximal and distal to the injury. Attempts at surgical repair are unlikely to be successful and are impractical to perform due to the delicate nature of the lymphatic vessels [6, 11]. In those patients presenting with chylothorax, initial management consists of adequate pleural drainage with placement of tube thoracostomies, with or without image guidance. Drainage must be adequate to evacuate all fluid and allow the collapsed lung to fully re-expand. Maneuvers to reduce the volume of chyle should then be undertaken. The patient may be made nothing per os (NPO) and placed on TPN.

Alternatively, the patient may be allowed a fat free diet enriched in medium-chain triglycerides. Use of octreotide or somatostatin, which reduces gastrointestinal secretion and absorption and subsequently may reduce chyle production, has also been reported [2–4, 13, 15]. Electrolytes, fluids, and fat-soluble vitamins should be monitored closely and aggressively replaced intravenously. Low and moderately low output chylothoraces, those with <500 and <1,000 mL/day, respectively, generally respond well to dietary manipulation and drainage without requiring invasive interventions. The overall success rate of conservative management has been reported to be as high as 88 % [2, 9, 10]. Once the fluid draining has cleared from milky to serous, and the output has decreased to less than 250 mL/day, a high-fat meal challenge should be given, if no increase in output or change in character of the drainage is noted, the chest tubes can be removed [15].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree