One of the most significant articles in the history of cardiology was published in 1930 under the rather unassuming title, Bundle-branch block with short P-R interval in healthy young people prone to paroxysmal tachycardia . The authors, whose names would be joined to form a well-known eponym, were Louis Wolff of Boston, John Parkinson of London, and Paul Dudley White of Boston. White was very interested in the long-term follow-up of patients that he had seen during his half-century career. In his 1967 book on the long-term follow-up of patients with various types of cardiovascular disease, White reported on 2 of the 11 patients that he and his coauthors had described in their original Wollf-Parkinson-White article. White explained that 1 of those patients was a physician who was in good health 36 years after the report was published.

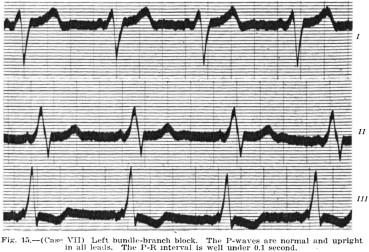

As a result of a chance encounter, I discovered that 1 of Wolff, Parkinson, and White’s original 11 patients was alive and well until he developed heart failure and died at the age of 83, >7 decades after they summarized his case in their classic article. BH was 11 years old when he was seen by Dr. (later Sir) John Parkinson at the London Hospital on April 13, 1929. The boy had a history of exhaustion, occasional pallor, and a varying pulse rate that was often slow. For a year he had had recurrent attacks lasting a few days at a time in which he was pale with a pulse rate of 40 to 65 beats/min. His blood pressure, cardiac examination, and orthodiagram (a special type of chest x-ray) were normal. The boy’s electrocardiogram (ECG) showed a short PR interval of <0.1 second and what the authors described as left bundle branch block ( Figure 1 ).

I learned about the patient’s subsequent history from his son and from a 1953 article that reported 5 patients with pheochromocytoma, 1 of whom was BH. The episodes that Parkinson had described in the 1930 report subsided. But 12 years later, when BH was aged 23 years, he began having “attacks of epigastric discomfort, followed by slow forceful palpitation, and sometimes throbbing headache, nausea, vomiting, and dyspnea.” The authors of the pheochromocytoma report noted that his spells were also accompanied by sweating, shivering, and “slight” bradycardia. His blood pressure rose during them; the highest reading was 254/154 mm Hg. Between the attacks, his blood pressure varied from 120/86 mm Hg to 170/110 mm Hg.

In 1949, when BH was 31 years old, he was diagnosed as having a pheochromocytoma. He was operated on at St Mary’s Hospital in London, and a very large tumor weighing 200 g was removed. Three years after surgery, the man was symptom free and a single blood pressure of 135/80 mm Hg was recorded. The authors did not mention an ECG. His son has told me that his father had had a full working life without paroxysms of tachycardia or other cardiac symptoms.

The question arises as to whether BH’s symptoms when Parkinson saw him at the age of 11 were due to the pheochromocytoma. The authors of the 1953 article from St Mary’s Hospital explained that between 23 and 31 years of age, BH had remissions of his pheochromocytoma symptoms lasting up to several months. However, there was an interval of a decade between his childhood symptoms, which they say had subsided, and the onset of his adult illness. Even so, the symptoms were quite similar. Between 10 and 11 years of age he had had recurrent attacks in which he was pale and had a slow pulse rate. His blood pressure on a single occasion was normal, but it was also sometimes normal in between his adult attacks. There is no way to answer this question, but it could well be that the tumor was present in childhood. When it was removed in 1949, it was the largest in the St Mary’s Hospital series.

One might also ask why this 11-year-old boy had an ECG in the first place, at a time when the examination was by no means routine. The answer lies in the fact that he was seen at the London Hospital where John Parkinson was in charge of the world-class cardiac department that Sir James Mackenzie had founded in 1913. Parkinson, a highly regarded cardiologist, had an electrocardiograph and an orthodiagram done on all of his outpatients. He recognized that the tracing was very unusual and showed it to Paul Dudley White, when the Boston cardiologist visited him in 1929. They had known each other since 1913, when White was doing research in London with electrocardiographic pioneer Thomas Lewis and Parkinson was Mackenzie’s first assistant. The 2 men, who were the same age, became lifelong friends.

Parkinson noted in a 1940 article that the classic electrocardiographic findings of short PR interval and bundle branch block pattern had been found only 3 times among 19,000 ECGs taken in his department. Wolff, Parkinson, and White labeled BH’s ECG as showing left bundle branch block. This diagnosis reflected conclusions that had been based on experiments on dogs that Thomas Lewis had done in 1916 and that Frank Wilson and George Hermann had done in 1920. However, they mixed up right and left bundle branch block. The correct interpretation was worked out from the electrical axis in the human heart in 1920 by George Fahr of Minneapolis, whose contribution has been overlooked. Wolff, Parkinson, and White concluded their 1930 article with a note that explained that they had used “the old nomenclature” and that “according to the new nomenclature, which is probably correct … one should read … ‘right bundle-branch block’ for ‘left’ in this paper.” Their youngest patient, BH, survived into the twenty-first century. Unlike the other 10 patients in their series, there is no evidence that he ever had episodes of paroxysmal tachycardia.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree