The term “coarctation” necessarily calls attention to a specific morphologic abnormality of the aortic isthmus. However, in this report, the author seeks to dispel the simplistic notion that coarctation is best characterized by isthmic obstruction, which is only 1 of an assemblage of abnormalities that include the proximal paracoarctation aorta, the distal paracoarctation aorta, the ascending aorta, the transverse aorta, the coronary arteries, the conduit arteries (radial, brachial, and carotid), the retinal vascular bed, dissecting aneurysms, cerebral aneurysms, vascular rings, systemic hypertension, and a decrease in left ventricular interpapillary muscle distance. Some of these abnormalities are secondary to the coarctation, such as collateral arteries and dissecting aneurysms. Others frequently or invariably coexist but are not secondary, such as bicuspid aortic valve and aneurysm of the circle of Willis. Still other abnormalities are seemingly contradictory, such as aneurysmal dilatation of the low-pressure distal paracoarctation aorta, while the high-pressure proximal segment does not dilate significantly. In conclusion, coarctation should be regarded as an assemblage of cardiovascular abnormalities rather than as isolated obstruction of the aortic isthmus.

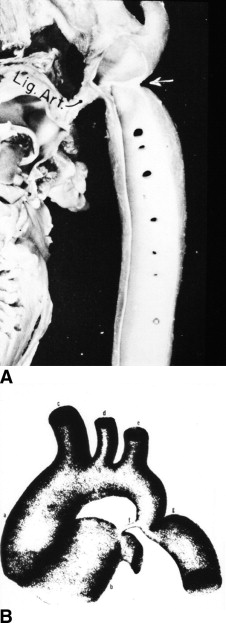

Coarctation of the aorta is usually and simplistically regarded as isolated obstruction of the aortic isthmus ( Figure 1 ) but in fact is a widespread disorder in which isthmic obstruction is only 1 of many abnormalities that include the proximal and distal paracoarctation aorta, the ascending and transverse aorta, the coronary arteries, conduit arteries (radial, brachial, and carotid), the retinal vascular bed, dissecting aneurysms, cerebral aneurysms, vascular rings, and systemic hypertension. Mild coarctation does not necessarily have a benign long-term course, underscoring that coarctation is more than a mechanical disorder.

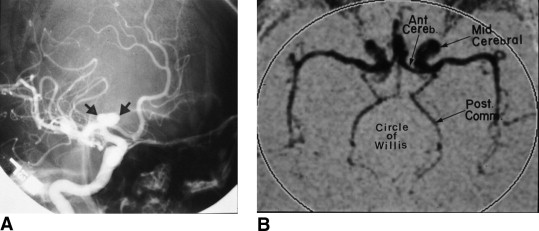

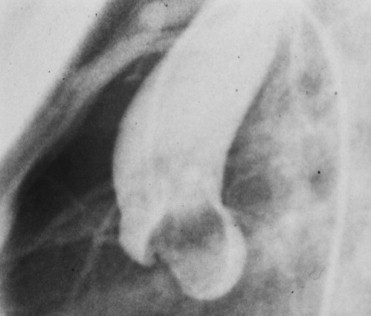

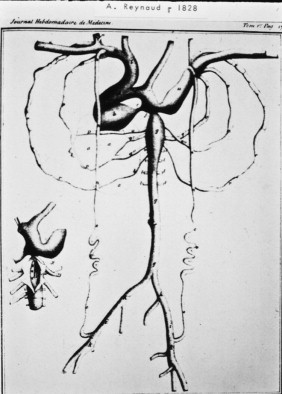

Why is this assemblage of abnormalities associated with aortic coarctation? Some of the abnormalities can be considered secondary to isthmic obstruction, such as collateral arteries, dissecting aneurysms, effects on the coronary arteries and on conduit arteries, and coarctation as a component of a vascular ring. Still other abnormalities frequently or invariably coexist but are not secondary, such an aneurysm of the circle of Willis ( Figure 2 ) and the distinctive corkscrew retinal arterioles that persist even after ideal resection ( Figure 3 ), while hypertensive retinopathy is conspicuous by its absence. The bicuspid aortic valve that often but not invariably coexists ( Figure 4 ) is almost always equally bicuspid. Other abnormalities are seemingly contradictory. The proximal paracoarctation aorta is a high-pressure, low-velocity segment, while the distal paracoarctation aorta is a low-pressure, high-velocity segment. Identical medial abnormalities are present in the 2 segments, but the distal low-pressure segment becomes aneurysmal, while the proximal high-pressure segment does not significantly dilate.

In 1760, the Prussian anatomist Johann Friedrich Meckel characterized coarctation of the aorta in terms of effect and cause as an “extraordinary dilatation of the heart which came from the fact that the aortic conduit was too narrow.” Jarcho’s illustrations, published between 1961 and 1963, are models of clarity and anatomic accuracy ( Figure 1 ).

Coarctation is typically located near the aortic attachment of the ligamentum arteriosum ( Figure 1 ). An obtuse indentation of the posterolateral wall of the aorta corresponds to an internal ridge or shelf that eccentrically narrows the aortic lumen, hence the Latin term “coarctatus,” which means contracted, tightened, or pressed together. The internal ridge that forms the coarctation consists of smooth muscle, fibrous tissue, and elastic tissue similar in composition to a muscular arterial ductus. Intimal proliferation distal to the ridge culminates in luminal narrowing. Extension of ductal tissue into the aortic wall normally does not exceed 30% of the aortic circumference, but in preductal coarctation, ductal tissue forms a circumferential sling that extends around the aorta. Aortic coarctation is represented by a localized constriction containing the ridge or shelf as just described. “Tubular hypoplasia” refers to uniform narrowing within the aortic arch. Tubular hypoplasia and localized coarctation and can coexist or occur independently. Less commonly, a relatively long segment of constriction extends beyond the left subclavian artery. When coarctation is located immediately distal to the origin of the left subclavian artery, which is usually the case, the left subclavian artery is dilated. A decrease in left ventricular interpapillary muscle distance often coexists and, in its extreme form, culminates in the single papillary muscle of a parachute mitral valve.

Abnormalities Secondary to the Coarctation

Thoracic and spinal canal collateral arteries are vascular sequelae that are secondary to the coarctation ( Figure 5 ). Patency of the ipsilateral subclavian artery is a precondition for the development of thoracic collateral arteries. When the orifice of the left subclavian artery is obstructed by the coarctation, left-sided arterial collaterals fail to develop. A subclavian steal can arise from retrograde flow down the ipsilateral vertebral artery.

Notching of the ribs is a classic radiologic sign of coarctation of the aorta caused by collateral flow through dilated, pulsatile posterior intercostal arteries ( Figure 6 ). Notches vary from rib to rib and from patient to patient and may be single, multiple, shallow, deep, broad, or narrow. Because notching originates in posterior intercostal arteries that run in intercostal grooves, the anterior ribs are spared because anterior intercostal arteries do not run in intercostal grooves. Benign aneurysms occasionally develop in intercostal arteries.