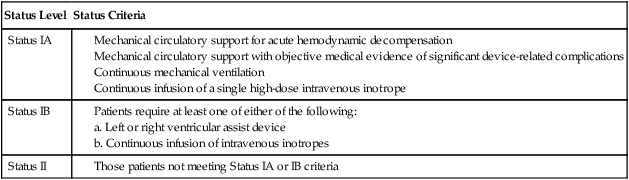

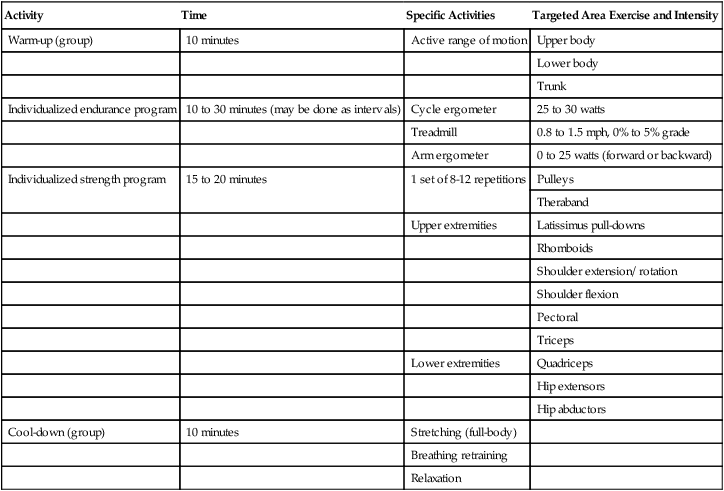

Transplantation of tissues and organs has been of interest to physicians and surgeons since the 18th century. Advances in our understanding of the immune system, development of immunosuppressive medications, and techniques such as cardiopulmonary bypass have provided the opportunity for successful organ transplants. In 1954, the first kidney was successfully transplanted. Other successful organ transplants include the first heart transplant in 1968, combined heart-lung transplant in 1981, and single-lung transplant in 1983.1 Organ transplantation has become a viable alternative to medical treatment of many conditions. Because of the success rates, many types of transplants are no longer considered experimental but are considered appropriate treatment for organ failure. As a result of improved survival, long-term outcomes are as important as short-term outcomes as a measure of successful transplantation. The number of Medicare-approved medical centers that perform lung and heart-lung transplants has grown to 50 in the United States, and there are 110 certified heart transplant centers.2 Over 2000 heart transplants and 1000 lung transplants have been performed annually since 2000. The 5-year survival rates for heart transplants of all status levels are reported as 70.9%; for lung transplants, 43.1%. Other national data on median waiting time and survival rates are presented in Table 40-1. Table 40-1 Heart/Lung Transplantation National Data Data from: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/latestData/step2.asp? The major cause of limitation in the number of organ transplants is the lack of organ supply with an increasing demand for organ transplantation. The number of patients who could benefit from transplant significantly exceeds the number of organs available. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) is an organization whose primary goal is to increase the availability of donated organs available and improve organ sharing. OPTN was established by the National Organ Transplant Act of the United States Congress in 1984 and is administered by the private, nonprofit organization United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), under contract with the U.S Department of Health and Human Services. An organ procurement organization (OPO) coordinates the management of the organ donor and family, the transplant center, and the recipient.3 The number of organs available for transplant remains well below the need for donor organs. Currently, there are over 110,000 individuals on the national waiting list for all organs, with over 3200 candidates waiting for heart transplant and approximately 1800 candidates waiting for lung transplant. A general list of criteria for patient selection for transplant is presented in Box 40-1. Names of patients on the waiting list are filed in the UNOS Organ Center, a centralized database that links transplant centers with OPOs. Once an organ donor has been identified, a computer-generated list of potential recipients is ranked, according to the criteria established for each organ. Criteria may include blood or tissue type, size of organ, medical status of the patient, and amount of time a patient has been on the waiting list. The organ procurement coordinator confers with the transplant surgeons until a potential recipient is identified. Surgical teams then travel to the donor hospital while the recipient is concurrently prepared for surgery. Heart, lung, and liver transplantation success is optimized when transplant occurs within 6 hours after removing the donated organ. Surgical methods that allow for longer travel times or changes in management of the donor organ have increased the number of available organs; however, the number of available organs still remains significantly below the need. Policies were updated by the UNOS in 2006 to decrease the number of patients dying while waiting for transplant. These changes increased the number of transplants for the most severely ill patients awaiting heart transplant.4 There are many ethical, psychological, and social concerns surrounding organ transplantation. Ethical issues relate to increasing potential donor sources and distributing available organs. Psychological issues include stress due to an unknown waiting time, the potential of moving from one’s home to a location near a transplant center, and possible employment disruption. The transplant process affects not only the individual patient, but the patient’s social support systems as well. This is highly significant because adequate social support is a factor in long-term transplant success and quality of life.5 Other bioethical considerations include how to allocate the available organs to individuals waiting for transplant. All patients are screened for medical and psychological conditions that would adversely affect the outcome of transplantation. The specific acceptance criteria are different for each organ; lung transplant criteria differ from heart transplantation criteria. OPTN policies specify that each transplant center will create its own specific policies.6 In general, waiting list time remains the primary factor that determines who is next in line to receive an available organ; however, other matching factors are considered for each available organ. Patients who are current smokers are not candidates for lung transplantation, although most centers allow former smokers to qualify for a lung transplant. Patients with documented alcohol abuse are not candidates for transplantation. Criteria are used so that individual preferences of team members are not given priority. In addition, ethnicity, gender, religion, and financial status are not part of the transplant criteria. There are many psychological issues associated with organ transplantation, such as feelings of uncertainty, upheaval associated with moving, and issues of psychological adjustment. The time spent waiting for a transplant can vary considerably. During the waiting period, patients struggle with the need to carry on their lives, knowing that at any moment they may be called to the hospital for transplant. In addition, the patient is torn between wanting to remain hopeful that a transplant will provide new life and the reality of knowing they have a terminal condition. Anxiety and depression have been identified as prevalent psychological issues related to transplant.7 The number of transplant centers in the United States is limited. Because donor organs are viable for only hours after removal from the donor, patients waiting for transplant are frequently required to live within a several-hour radius of the transplant center. Patients need information and logistics assistance for relocation to a transplant center. They may also require emotional and financial support for this transition.8 The demands of waiting and relocation to the transplant city put considerable stress on the patient and their significant others. Those patients who relocate to transplant centers may have the most difficult time psychologically, especially when they leave family and significant others behind. The psychological stresses are somewhat different for spouses. Spouses speak of the struggle to remain hopeful, yet plan for a future that may not include their loved one. If the patient and spouse move together to a new city to wait for transplant, they may find themselves with more time together than previously. In this “forced retirement” situation, new stresses are added to relationships. Transplant teams usually include a psychologist or social worker to whom patients may be referred for individual or family counseling if needed. Other concerns include psychological adjustment and the effect of social supports on mediating coping skills. Feelings of being useless are common because patients waiting in a new city are outside of their own environment and must find some meaningful activities. Coping strategies appear to strengthen psychological outcomes. After transplant, patients are often emotionally overwhelmed with a feeling of gratefulness that they are alive and feelings of guilt that someone else’s grief has given them a chance to rejoice. A strong support system is considered an essential component of a successful transplant and improves psychosocial outcomes after transplantation.9 Therapists can assist patients by listening to feelings, being supportive, and encouraging participation in support groups. Support groups that include patients waiting for transplants as well as posttransplant patients can offer significant psychosocial support. Spouses and significant others also benefit from group support. Patients are referred for heart transplantation for end-stage cardiac conditions. The primary diagnoses for adults requiring a heart transplant are severe coronary artery disease (38%) and end-stage cardiomyopathy/heart failure (53%). In children under 1 year, the primary diagnosis requiring transplant is congenital cardiac abnormalities; for ages 1-10, cardiomyopathy.10 Patients with heart failure generally meet the heart transplant selection criteria if they have New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III or IV heart failure that is unresponsive to medical management. Specific criteria for recipient status vary somewhat from center to center, although International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) criteria for listing are generally followed.11 Exercise testing criteria can be used to guide transplantation. Patients who complete a maximum test may be eligible for a heart transplant if peak Recipients waiting for heart transplantation are classified based on severity of disease. Patients in the worst medical condition (Status IA) are placed higher on the transplant recipient list. Table 40-2 outlines the criteria for each level of heart transplant recipient status. Table 40-2 Heart Transplant Recipient Status Source: http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/PoliciesandBylaws2/policies/pdfs/Policy_9.pdf The main rehabilitation goal in the preoperative period is to prevent losses of physical function. Maintenance of range of motion, soft tissue extensibility, and muscle strength are suggested goals. Although patients with severe disease may be unable to participate in therapy, cardiac rehabilitation is an effective treatment for improving functional status of patients with significant heart failure and those with LVADs, whether or not transplantation is anticipated.12,13 Recent literature demonstrates that medically supervised exercise training is both safe and effective at improving aerobic capacity and physical function in patients with LVAD devices awaiting heart transplantation. Patients are referred for lung transplantation for end-stage pulmonary conditions. The primary diagnoses for adults requiring a lung transplant are severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (44%), idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) (17%), and cystic fibrosis (CF) (15%). Other conditions include pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH). The guidelines for selection of patients for the lung transplant waiting list were updated by the ISHLT in 2006 and include specific criteria for the most common pulmonary conditions.14,15 Within the disease-specific listing criteria for COPD, the guidelines include a BODE (body mass index, airflow obstruction, dyspnea, and exercise capacity) score of 7-10. The BODE is more useful than measures of airflow obstruction in predicting mortality from COPD; higher scores are associated with increased mortality.16 Before 2005, patients who had accrued the most time on the waiting list were given priority for lung transplants. The change to a lung allocation score now gives priority for transplants to those patients who have a greater medical urgency for transplant. The lung allocation score is based on “(i) waitlist urgency measure (expected number of days lived without a transplant during an additional year on the waitlist), (ii) posttransplant survival measure (expected number of days lived during the first year posttransplant), and (iii) transplant benefit measure (posttransplant survival measure minus waitlist urgency measure).”17 The urgency and survival measures are based on factors that predict risk for death in patients with lung transplant and include functional status as well as physiological measures. This change has increased the number of transplants for patients with IPF and slowed the number of transplants for COPD.14 Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is characterized by scarring of lung parenchyma leading to decreased lung volumes and decreased diffusing capacity. Risk factors for mortality include the lung pathology, pulmonary function results, physical function from the 6-minute walk test, and respiratory failure.14 Criteria for listing of patients with IPF include a decrease in FVC of 10% or more during 6 months and pulse oximetry less than 88% during a 6-minute walk test.15 Patients with IPF waiting for lung transplant who walked less than 679 feet had higher mortality than those who walked longer distances.18 Recent advances in vasodilator therapy for patients with pulmonary artery hypertension and poor survival of patients with PAH after transplant have reduced the number of patients with PAH who receive lung transplants. The criteria for listing patients with PAH include an NYHA class III or IV status on the maximal vasodilator therapy and 6-minute walk test of less than 350 meters.15 In patients with cystic fibrosis, the predictors of mortality include declining FEV1 and chronic infection. The current criteria for transplant include FEV1 less than 30% of predicted, as well as other markers of declining pulmonary function.19 The causes of exercise limitation in people with chronic lung conditions are both ventilatory and musculoskeletal. Muscle changes in pulmonary conditions include decreased muscle oxidative capacity and muscle weakness.20 Reasonable goals for pretransplant rehabilitation include improvement in muscle strength in lower extremity musculature, functional upper extremity muscle strength and endurance, functional shoulder and chest wall range of motion, demonstration of coordinated diaphragmatic breathing with exercise and activities, and improved cardiovascular endurance. Because of the significant effect of immunosuppressive medications on muscle strength, a greater emphasis is placed on resistance training in a patient awaiting lung transplantation than in most typical pulmonary rehabilitation programs. An example of a preoperative pulmonary rehabilitation program is outlined in Table 40-3. Table 40-3 Preoperative Pulmonary Rehabilitation

The Transplant Patient

Background

Heart

Lung

Number of transplants, 2005-2010

12,660

8744

Median waiting time (in days), 2003-2004

Status 1A, 50

Cystic fibrosis, 587

Status 1B, 78

COPD, 1349

Status 2, 309

Pulmonary fibrosis, 1115

1-year survival (all status)

87.3%

83.1%

5-year survival

70.9%

46.3%

Organ Donation

Issues Associated with Transplantation

Ethical Considerations

Psychological and Social Considerations

Rehabilitation of the Transplant Patient

Pretransplant Rehabilitation

Heart Transplant and End-Stage Cardiac Disease

is ≤14 mL/kg/min, or ≤12 mL/kg/min if on a beta blocker.11

is ≤14 mL/kg/min, or ≤12 mL/kg/min if on a beta blocker.11

Status Level

Status Criteria

Status IA

Status IB

Status II

Lung Transplant and End-Stage Pulmonary Disease

Activity

Time

Specific Activities

Targeted Area Exercise and Intensity

Warm-up (group)

10 minutes

Active range of motion

Upper body

Lower body

Trunk

Individualized endurance program

10 to 30 minutes (may be done as intervals)

Cycle ergometer

25 to 30 watts

Treadmill

0.8 to 1.5 mph, 0% to 5% grade

Arm ergometer

0 to 25 watts (forward or backward)

Individualized strength program

15 to 20 minutes

1 set of 8-12 repetitions

Pulleys

Theraband

Upper extremities

Latissimus pull-downs

Rhomboids

Shoulder extension/ rotation

Shoulder flexion

Pectoral

Triceps

Lower extremities

Quadriceps

Hip extensors

Hip abductors

Cool-down (group)

10 minutes

Stretching (full-body)

Breathing retraining

Relaxation

The Transplant Patient