31 The Role of the Cardiac Surgeon

The role of the cardiac surgeon in the cath lab can be broadly described in three categories. First, the surgeon has been traditionally viewed as a standby operator backing up the interventional cardiologist in case of any untoward complication or emergency requiring surgical intervention. The need for this role waxes and wanes with the advent and subsequent mastery of each new procedure adopted in the cath lab. Formal surgical standby for routine PCI, where a surgeon is preemptively notified and is waiting in the hospital, no longer exists in most centers, as complications requiring surgical intervention have become quite uncommon in established centers. However, current published guidelines for elective PCI still recommend the availability of an experienced surgical team that can be activated quickly in the event of a cath lab emergency.1 Some evidence exists that primary PCI performed at certain highly experienced centers without an existing aortocoronary bypass program may be reasonable and have some benefit over the alternative use of fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction (MI).2 This concept is currently not promoted by the consensus of the cardiovascular community.

Historical Perspective

Historical Perspective

Throughout history, alongside their colleagues in cardiology, radiology, and other disciplines, surgeons have participated in pioneering the majority of invasive procedures and technical innovations in cardiovascular medicine. The input of the surgeon has always been regarded as the gold standard for advice on the anatomic aspects and physiologic practicality of a proposed invasive procedure. With their surgical feasibility proven, new clinical techniques have been adopted by the medical community and have spawned numerous specialties based on the initial curiosity and investigation of the surgeon and his colleagues. Not unique to cardiovascular medicine, this evolution and translation of skill sets has occurred in several areas such as gastroenterology with endoscopy; pulmonary critical care with intensive care, bronchoscopy, and ventilator management; and most recently with interventional radiologists performing vascular intervention, tumor biopsy, thoracostomy, abscess drainage, and more. The field of interventional cardiology has likewise evolved with surgical advancement. Before the advent of modern angiography, surgeons routinely performed their own angiograms in order to define the vascular anatomy prior to embarking on surgical intervention. The concept of having proper imaging or a “roadmap” before open-heart surgery has been a well-accepted practice in cardiovascular surgery for decades. Looking back, in 1929, Werner Forssmann, a surgical trainee at the time, passed a urinary catheter through the vein in his own arm to his heart and subsequently irradiated himself in spite of the reprimand of his department and his lab assistant’s discouragement. After successfully demonstrating the catheter to be in the right atrium, Forssmann was credited with performing the first cardiac catheterization.3 Forssmann received the Nobel Prize in 1956 along with Andre Coumand and Dickinson Richards, for “the role of heart catheterization and angiocardiography in the advancement of medicine.”4 In 1953, Sven-Ivar Seldinger, who was briefly trained as a surgeon before becoming a radiologist, developed a percutaneous approach for the introduction of vascular catheters for both right and left heart catheterization.5 This technique is now the most common percutaneous approach used for gaining access to the vascular tree. In 1977, Andreas Gruentzig, along with his surgical colleague Richard Myle, inflated the first catheter-guided balloon in a coronary artery intraoperatively during a coronary bypass operation.3,6 Gruentzig’s novel procedure eventually became known as percutaneous transluminal catheter angioplasty (PTCA) and set the stage for modern interventional cardiology and PCI.7 The list of events and milestones that illustrates how surgeons have remained steadfast beside their nonsurgical colleagues as a fundamental part of developing and advancing nearly every invasive discipline in medicine is quite impressive. Today, the cardiac surgeon is likewise a key team member in any successful and innovative interventional program. The magnitude and activity of the surgeon’s role in the day-to-day proceedings of the interventional suite is not always a steady one; rather, it usually depends on the risk of each intervention to the patient and the learning curve associated with the introduction of each new procedure, along with the level of the hands-on interest of the individual surgeon. As new procedures that propose to alter the current standard of care, for example, trans-catheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI), are adopted into practice, it is critical for the surgeon’s role to be increased while a new comfort zone of safety and efficacy is reached by the entire interventional team.

Surgical Standby

Surgical Standby

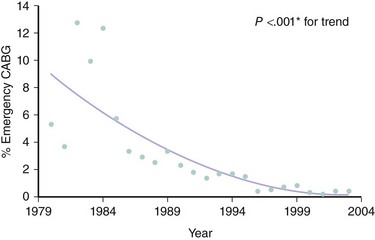

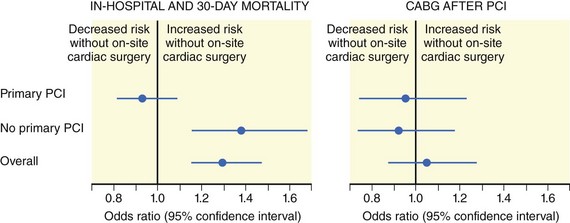

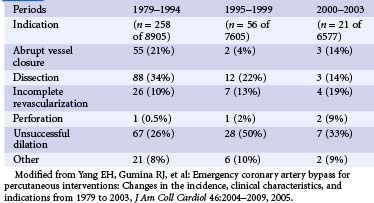

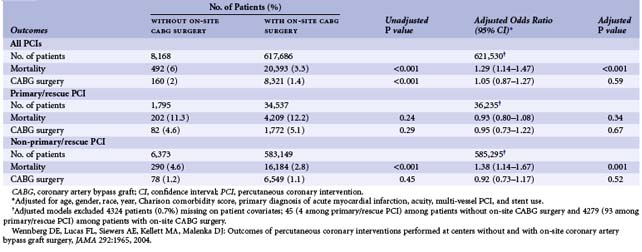

During the early years of PTCA and PCI, surgeons, by necessity, were compelled to remain in house and on “surgical standby” for any urgent consultations and surgical emergencies that resulted from early interventional procedures. Fraught with technical pitfalls and clinical unknowns, more often than not, early complications in the cath lab necessitated an emergent trip to the operating room, often with a patient in extreme cardiogenic shock.8–10As a result, indications for emergency CABG after failed PCI became well established over time. The most common indications include abrupt vessel closure, dissection, incomplete revascularization, perforation, and unsuccessful dilation or PCI in addition to other miscellaneous clinical scenarios (Table 31-1).11 As angiography, PTCA, and surgical techniques improved and medical equipment became more advanced, surgeons were no longer required to remain in such proximity to the cath lab.12,13 This was particularly true with the introduction of the Gianturco–Roubin stent and its rapid adoption as a “bailout catheter” by the interventional cardiology community.14,15 Almost uniformly, and for decades, active PCI centers have enjoyed a steady reduction in the percentage of cases requiring emergency CABG after failed PCI (Fig. 31-1).16 However, it still must be carefully noted that despite universal trends demonstrating decreased morbidity and mortality from PCI, the consequences of complications in the interventional suite remain potentially catastrophic. Thus, it is still common practice today, and also recommended by the ACC/AHA/SCAI Practice Guidelines, that the majority of elective PCI be performed at centers with an active open-heart surgery program, as certain interventional decisions must be discussed with a cardiac surgeon before proceeding with PCI.1 In the event of emergent need for aortocoronary bypass, outcomes have been shown to be better in centers with an open-heart surgery program (Table 31-2; Fig. 31-2).11,16 According to current guidelines, on-site surgical backup should provide emergency hemodynamic support and expeditious revascularization to deal with complications that cannot be addressed in the cath lab (Table 31-3). Often, these complications during PCI are life threatening in terms of hemodynamic stability and are associated with prolonged periods of ischemia. Such emergencies require the availability of a cardiac surgery team experienced in emergency aortocoronary operations. Thus, on-site cardiac surgical backup should provide readily available cardiac surgical support in the event of a hemodynamic or ischemic emergency. On-site cardiac surgical backup is also a surrogate for an institution’s overall capability to provide a highly experienced and promptly available team to respond to a cath lab emergency.1 The issues of cardiac surgical backup and the level of committed resources that are needed are frequently revisited; most centers today use the “first-available operating room” model to remain efficient and to maximize resources. Some centers rely on off-site surgical backup, but this is the exception rather than the rule, and such practice exposes the patient to a finite, but potentially fatal, risk and is deemed unnecessary in most areas of the country. Recommendations for primary PCI for ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) without on-site cardiac surgery are given in Table 31-4.17 The apparent success of centers performing PCI without on-site cardiac surgery programs, among other things such as operator experience and volume, can be attributed to fairly strict patient selection (Table 31-5) and criteria (Table 31-6).18 It should be noted that in low-volume centers (<200 PCIs per year), adverse event estimates lose stability and may therefore be unreliable (Fig. 31-3).1

TABLE 31-1 Indications for Emergency Coronary Bypass Surgery after Failed Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

TABLE 31-2 Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting and Mortality Rates Following Percutaneous Coronary Intervention at Hospitals without and with On-site Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting Surgery

TABLE 31-3 Role of On-site Cardiac Surgical Back-Up for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention

| Class I |

| Elective PCI should be performed by operators with acceptable annual volume (at least 75 procedures per year) at high-volume centers (more than 400 procedures annually) that provide immediately available on-site emergency cardiac surgical services. (Level of Evidence: B) |

| Primary PCI for patients with STEMI should be performed in facilities with on-site cardiac surgery. (Level of Evidence: B) |

| Class III |

| Elective PCI should not be performed at institutions that do not provide on-site cardiac surgery. (Level of Evidence: C)* |

* Several centers have reported satisfactory results on the basis of careful case selection with well-defined arrangements for immediate transfer to a surgical program (333–337; 348–353). Wennberg et al, found higher mortality in the Medicare database for patients undergoing elective PCI in institutions without on-site cardiac surgery (6.0% versus 3.3% respectively. Adjusted P Value <.001). This recommendation may be subject to revision as clinical data and experience increase.

Wennberg DE, Lucas FL, Siewers AE, Kellett MA, Malenka DJ: Outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions performed at centers without and with onsite coronary artery bypass graft surgery, JAMA 292:1965, 2004.

TABLE 31-4 Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention for ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction without On-site Cardiac Surgery

| Class IIb |

| Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) for patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) might be considered in hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery provided that appropriate planning for program development has been accomplished. This should include appropriately experienced physician operators (more than 75 total PCIs and, ideally, at least 11 primary PCIs per year for STEMI); an experienced catheterization team on an all-day, all-week call schedule; and a well-equipped catheterization laboratory with digital imaging equipment, a full array of interventional equipment, and intra-aortic balloon pump capability. A proven plan for rapid transport to a cardiac surgery operating room in a nearby hospital with appropriate hemodynamic support capability for transfer should be in place. The procedure should be limited to patients with STEMI or MI with new or presumably new left bundle branch block on electrocardiogram (ECG) and should be performed in a timely fashion (goal of balloon inflation within 90 minutes of presentation) by persons skilled in the procedure (at least 75 PCIs per year) and at hospitals performing a minimum of 36 primary PCI procedures per year. (Level of Evidence: B) |

| Class III |

| Primary PCI should not be performed in hospitals without on-site cardiac surgery and without a proven plan for rapid transport to a cardiac surgery operating room in a nearby hospital or without appropriate hemodynamic support capability for transfer. (Level of Evidence: C) |

TABLE 31-5 Patient Selection for Primary Percutaneous Coronary Intervention and Emergency Aortocoronary Bypass at Hospitals without On-site Cardiac Surgery

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree