Despite advances in evidence-based treatments, the morbidity and mortality of congestive heart failure remain exceedingly high. In addition, the costs associated with recurrent hospitalizations and advanced therapies, such as implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs), left ventricular assist devices, and heart transplantation, place a substantial financial burden on the health care system. The present criteria for risk stratification in patients with heart failure are inadequate and often prevent the allocation of appropriate treatment. Patients who have received ICDs as primary prevention for sudden cardiac death often receive no device therapy in their lifetime, whereas other patients with left ventricular dysfunction die suddenly without meeting criteria for ICD implantation.

During the past decade, nuclear cardiologists have developed a new imaging tool for assessing myocardial sympathetic activity. Altered sympathetic activity is present in HF and can be assessed using radioiodinated metaiodobenzylguanidine (known as I-123 MIBG or MIBG). I-123 MIBG is a guanethidine analog that accumulates in the myocardium. Measurement of late I-123 MIBG uptake, as calculated by the heart to mediastinum activity ratio, can predict the risk of subsequent cardiac death.

I-123 MIBG was approved in 2013 by the US Food and Drug Administration for myocardial imaging, but utilization to date has been limited. Although reasons for this potential underutilization are multifactorial, the lack of close co-operation among imaging specialists and HF clinicians has reduced the potential role of I-123 MIBG imaging in the management of patients with HF.

In July 2014, a group of key opinion leaders in the fields of nuclear cardiology, HF, and electrophysiology met to discuss risk assessment in HF and limitations of the published literature regarding I-123 MIBG and to provide suggestions for additional research. Consensus opinion regarding the present and potential future role for I-MIBG was developed and is the focus of this report.

The Burden of HF

The American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Guidelines describe HF as a “complex clinical syndrome that results from any structural or functional impairment of ventricular filling or ejection of blood.” The diagnosis is supported by history, physical examination findings, laboratory data, and objective diagnostic testing.

Currently, ∼5.8 million Americans have HF, and about 870,000 new HF cases are diagnosed annually. HF is one of the few cardiovascular conditions whose incidence has not decreased in the past 20 years. Given the aging US population, the prevalence of HF is expected to increase 46% from 2012 to 2030. The mortality rates for HF remain at 50% within 5 years of the initial diagnosis. Costs associated with management of HF will undoubtedly increase as well. Patients with HF account for ∼1 million hospital admissions annually, with an additional 2 million patients with HF documented as a secondary diagnosis at the time of admission. Readmission rates for HF remain ∼25%. In 2013, physician office visits for HF cost $1.8 billion and total costs associated with HF exceeded $30 billion. These figures include the cost of health care services, medications, and lost productivity. The average cost of hospitalizations for HF was $23,077. Projections are that by 2030, the total costs associated with HF will increase ∼127%, resulting in a projected annual cost of $69.7 billion; this cost correlates to approximately $244 for every American adult. Therefore, HF continues to be a major health care issue, with an enormous prevalence and huge contributor to health care expenditures.

HF can be divided into HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and HF with preserved ejection fraction. Systolic and diastolic dysfunctions may coexist in many patients. When classifying patients who have HF, left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) measurements are considered a key determinant because of differing patient demographics, co-morbid conditions, prognosis, and response to therapies. Most clinical trials select patients based on LVEF measurement. Systolic HF, or HRrEF, is usually defined as HF manifestations associated with LVEF ≤40%. The severity of HF is categorized both by the New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification and AHA classification. More advanced stages by each classification are associated with worsening prognosis as seen in Table 1 .

| ACCF/AHA Stages of HF | NYHA Functional Classification | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| A | At high risk for HF but without structural heart disease or symptoms of HF | None | |

| B | Structural heart disease but without signs or symptoms of HF | I | No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause symptoms of HF. |

| C | Structural heart disease with prior or current symptoms of HF | I | No limitation of physical activity. Ordinary physical activity does not cause symptoms of HF. |

| II | Slight limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but ordinary physical activity results in symptoms of HF. | ||

| III | Marked limitation of physical activity. Comfortable at rest, but less than ordinary activity causes symptoms of HF. | ||

| IV | Unable to carry on any physical activity without symptoms of HF, or symptoms of HF at rest. | ||

| D | Refractory HF requiring specialized interventions | IV | Unable to carry on any physical activity without symptoms of HF, or symptoms of HF at rest. |

Sympathetic Nervous System in HF

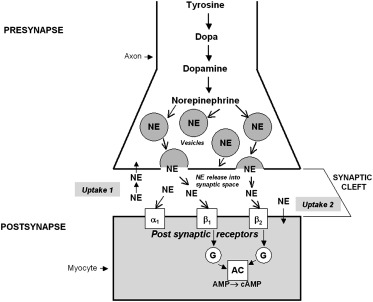

It is known that activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) occurs in systolic HF as shown in Figure 1 . Overactive sympathetic innervation involves increased release of norepinephrine (NE), the main neurotransmitter of the cardiac SNS. In response to sympathetic stimulation, NE is released from vesicles into the neuronal synaptic cleft. The released NE binds to postsynaptic beta-1, beta-2, and alpha-receptors; amplifies adenyl cyclase activity; and produces the desired cardiac stimulatory effects. NE is then reabsorbed into the presynaptic space for storage or catabolic disposal, terminating the synaptic response by the uptake-1 pathway. The increased release of NE usually correlates with decreased NE reuptake, which further increases circulating NE levels. This abnormal activation of the SNS eventually leads to further disease progression.

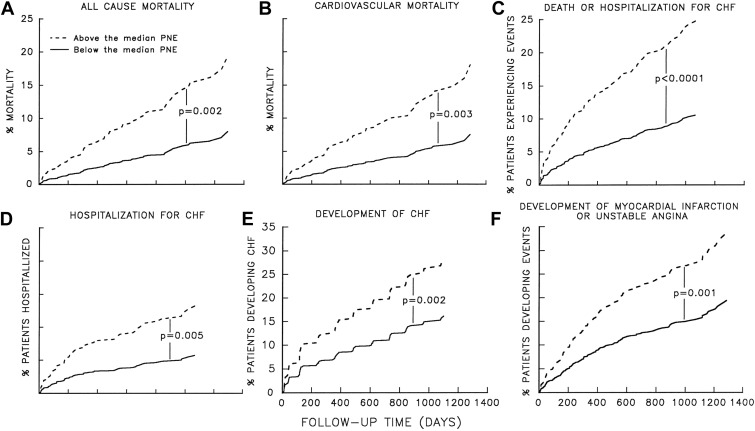

Excess sympathetic stimulation leads to increased myocardial stress, ischemia, and fibrosis. Elevated NE levels and the degree of sympathetic activation correlate with prognosis. Increasing levels of plasma NE activity are associated with worsening prognosis in patients with both asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction and HFrEF. As seen in Figure 2 , all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, development of HF, hospitalization for HF, and development of acute coronary artery syndrome are all more likely in the presence of increasing plasma NE activity.

Sympathetic Nervous System in HF

It is known that activation of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) occurs in systolic HF as shown in Figure 1 . Overactive sympathetic innervation involves increased release of norepinephrine (NE), the main neurotransmitter of the cardiac SNS. In response to sympathetic stimulation, NE is released from vesicles into the neuronal synaptic cleft. The released NE binds to postsynaptic beta-1, beta-2, and alpha-receptors; amplifies adenyl cyclase activity; and produces the desired cardiac stimulatory effects. NE is then reabsorbed into the presynaptic space for storage or catabolic disposal, terminating the synaptic response by the uptake-1 pathway. The increased release of NE usually correlates with decreased NE reuptake, which further increases circulating NE levels. This abnormal activation of the SNS eventually leads to further disease progression.

Excess sympathetic stimulation leads to increased myocardial stress, ischemia, and fibrosis. Elevated NE levels and the degree of sympathetic activation correlate with prognosis. Increasing levels of plasma NE activity are associated with worsening prognosis in patients with both asymptomatic left ventricular dysfunction and HFrEF. As seen in Figure 2 , all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, development of HF, hospitalization for HF, and development of acute coronary artery syndrome are all more likely in the presence of increasing plasma NE activity.

Sudden Cardiac Death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is a leading cause of mortality in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. In the United States, the annual incidence of SCD is estimated to be 180,000 to 450,000 cases per year. SCD accounts for >50% of all coronary heart disease deaths and also accounts for ∼15% to 20% of overall deaths. Extrapolated data from the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study estimate risk-adjusted incidence of SCD was 60 per 100,000 per year, which is estimated to be 212,910 per year in the United States.

The burden of HF and the risk of SCD mandate that better risk prediction tools need to be defined. Despite improvements in therapy, the mortality rate associated with HF remains unacceptably high. Appropriate strategies need to be defined to more effectively implement treatments and to improve patient management. There is a large body of literature describing the risk of SCD associated with HF, particularly HFrEF. There has been much written to define the benefit of prophylactic implantable cardiac defibrillators (ICDs) in reducing SCD in these patients.

The use of prophylactic ICD implantation for primary prevention in patients with HF has grown exponentially since the 1990s, with more than 100,000 implanted in the United States each year. Optimizing patient selection has been an issue associated with ICDs as physicians have questioned the appropriate role of ICD therapy for SCD prophylaxis for more than a decade, calling for better risk stratification to reduce the clinical and economic repercussions of inappropriate use.

The initial effectiveness of ICDs was first demonstrated as secondary prevention therapy in high-risk patients. A meta-analysis of 3 landmark trials, Antiarrhythmic’s Versus Implantable Defibrillators, Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg, and Canadian Implantable Defibrillator Study found a 50% reduced risk for arrhythmic death with the device compared with medical therapy and a 28% reduced risk for overall death. It is, therefore, apparent that ICDs have significantly reduced the risk of SCD. The 2013 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Guidelines for management of HF provide the follow recommendations regarding ICD use:

- •

ICD therapy is recommended for primary prevention of SCD to reduce total mortality in selected patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy or ischemic heart disease at least 40 days after myocardial infarction (MI) with LVEF of ≤35% and NYHA class II or III symptoms on chronic guideline-mediated medical therapy, who have a reasonable expectation of meaningful survival for >1 year.

- •

ICD therapy is recommended for primary prevention of SCD to reduce total mortality in selected patients at least 40 days after MI with LVEF ≤30%. NYHA class I symptoms while receiving guideline-mediated medical therapy, who have reasonable expectation of meaningful survival for >1 year.

A 2010 meta-analysis found that ICDs reduced the risk for arrhythmic mortality by 60% in those patients with LVEF <35% and who were at least 40 days from an MI or at least 3 months from coronary revascularization (95% confidence interval 0.27 to 0.67). These findings formed the basis of the 2013 guidelines for ICD therapy issued from 8 leading cardiovascular organizations, including the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology.

Despite well-established guidelines for primary prevention with ICD implantation, there remain concerns regarding optimal utilization. In Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II and Sudden Cardiac Death in Heart Failure Trial, ∼20% to 25% of patients with ICDs still die of sudden death. The benefit of ICDs is uniform; however, several studies suggest that sudden death reduction can vary greatly, from 25% to 90%. Although the guidelines offer specific ejection cutoffs for implantation of ICD, sudden death risk and benefit vary across the spectrum of LVEF indexes and clinical HF severity.

Adding to the complexity and application of criteria, current guidelines rely solely on LVEF as the risk-stratifying indicator for primary ICD implantation. However, it is well known that LVEF values vary based on the assessment technique used, including echocardiography, radionuclide angiography, gated single-photon emission computed tomography, invasive left ventriculography, and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. There is a significant intraobservation and interobservation variation associated with all these techniques. These variations may lead to unintentional failure to adhere to evidence-based guidelines for ICD implantation. There are data to suggest that LVEF alone may be an inadequate predictor of SCD risk in some populations. For example, the Oregon Sudden Unexpected Death Study demonstrated that 30% of sudden death patients would not have fulfilled criterion for ICD implantation. Therefore, ∼1/3 of patients with SCD would have had prophylactic ICDs and only 1/3 of evaluated cases of SCD would have qualified for prophylactic ICDs based on LVEF criteria. Furthermore, other studies suggest underuse of ICD therapy, particularly in women and minorities.

There are risks associated with ICD implantation. Studies find that up to 1/4 of patients with an ICD experience inappropriate shocks, which may significantly affect quality of life, as well as morbidity and mortality. Other potential complications, which may occur in up to 10% of patients, include pacing issues, triggering of arrhythmias after CRT, device infections, and hardware malfunction leading to device recalls. In addition, most patients will need at least 1 ICD replacement over their lifetime, with 40% requiring 2 replacements. This, in turn, may result in additional complications and costs.

Cost-effectiveness of ICDs

Multiple studies have shown that the cost-effectiveness of ICDs for primary prevention clearly varies across populations studied and duration followed. The short-term cost-effectiveness tends to exceed the >$50,000 incremental cost-effectiveness ratio typically considered acceptable. After several years, however, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio falls to an acceptable range. Risk stratification is key when considering cost-effectiveness. A 2002 report found that ICD therapy in patients with a high risk of SCD but a low risk of non-SCD was cost effective, whereas the benefits and cost-effectiveness were substantially lower in patients with lower ratios of SCD to non-SCDs. Patients who are likely to die sooner of pump failure have less benefit from ICD implantation.

Another analysis used ≤$75,000 per quality-adjusted life-years to evaluate cost-effectiveness in a population with previous MI and no sustained ventricular arrhythmia. The authors found that the cost-effectiveness of ICD therapy over the patient’s lifetime compared with amiodarone was of borderline value for those with LVEF of ≤30% ($71,800 per quality-adjusted life-years).

Thus, there remains a need for improved risk stratification in determining which patients can receive the greatest benefit from prophylactic ICD implantation. These strategies require algorithms that extend beyond LVEF criteria alone. These factors may include patient age (less benefit is seen in those age ≥70 years), prognosis (ICD implantation is not recommended in those with <1-year life expectancy), functional status and baseline quality of life, type of cardiovascular disease, residual ischemic burden, and the presence of medical co-morbidities. Given the high cost of ICDs, and their impact on patient quality of life, clinicians need to consider factors beyond LVEF, including overall clinical status and co-morbidities, HF risk assessment models, and the determination of myocardial sympathetic activity when choosing the most appropriate patients for ICD therapy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree