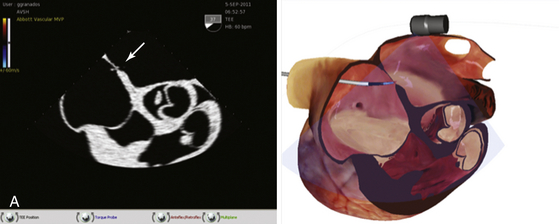

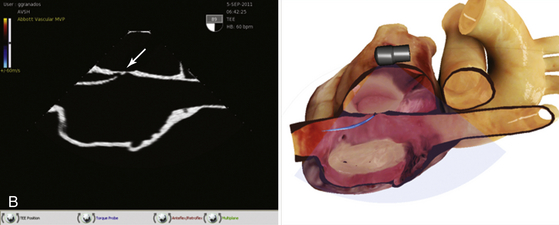

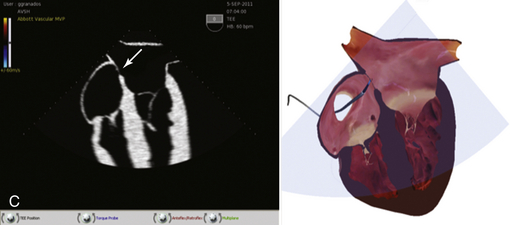

Chapter 1 There are no accreditation standards and no training programs for structural intervention. The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions has published a core curriculum for structural heart interventions.1–4 This will most easily be utilized by training programs, but it is a useful guide for the already-practicing interventional physician interested in this field. Structural procedures have been divided into basic and complex groups (Boxes 1–1 and 1–2). This division is a useful way to define which procedures might be adopted early in an operator’s experience. Imaging modalities have become a critical part of the structural interventional knowledge base. Patient evaluation for valve and structural procedures is easily as important as performance of the procedure itself. The interpretation of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging, as well as cardiac and vascular studies are new for many interventional physicians, and experience with these studies is a key part of developing a structural program. The interpretation and use of transthoracic, transesophageal, and intracardiac echocardiographic studies is integral to this field. Most structural catheterization laboratories now have an additional permanent monitor screen in the procedure room for the display of echo imaging.5 Although many interventional cardiologists have a strong background in imaging, just as many do not. The reliance on echocardiographic guidance for procedures for percutaneous mitral repair and especially for intracardiac shunt closure creates a substantial demand for this imaging skill set. Whereas courses exist for the acquisition of echo skills, the use of the imaging for interventional procedures is unique to the catheterization lab and requires an increasingly specialized background. One of the best pathways for entry into a particular procedure is to become involved in a research trial. The trial process provides training and provides a way into a procedure at a point when the playing field is level and no one has a substantial background in that specific procedure.6 A key part of training for many of the newer device trials has been simulation. Several companies have developed simulator equipment that allows practitioners to practice a new procedure. The haptics, or feel, of the procedure can be taught to some degree. The specifics of device preparation and use are easily incorporated into simulation programs. Decision making regarding the technique of the procedure or the management of a patient throughout the course of the procedure can be incorporated into simulation as well. A relatively new development has been the creation of a purely software-based simulator for training physicians in the use of percutaneous mitral repair. The simulator displays fluoroscopic, echocardiographic, and three-dimensional anatomic renderings that all move in synchrony as various procedure maneuvers are performed (Figure 1–1). Figure 1–1 A, Software-based simulator displays echocardiographic and three-dimensional anatomic renderings that all move in synchrony as various procedure maneuvers are performed. This image shows a short-axis transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) view to guide transseptal puncture for percutaneous mitral repair. The arrow shows the tip of the transseptal needle “tenting” the atrial septum. The short axis identifies the anteroposterior location of the puncture. B, Bicaval TEE view demonstrates the superoinferior location of the puncture. As in A, the right-sided image is a three-dimensional rendering of where the echo plane is obtained. C, Four-chamber TEE view demonstrates the height of the puncture above the plane of the mitral valve.

The Growing Specialty of Adult Structural Heart Disease

1.1 Core-Curriculum for Structural Intervention

1.2 Acquiring Skills for Structural Intervention

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine