This article provides narration of the events during the development of ergonovine maleate infusions for detecting coronary artery spasm at the Cleveland Clinic in 1973. This was the first safe, reproduceable and reliable test for angiographic visualization of the pathophysiology associated with the Prinzmetal Syndrome termed “angina inversa”.

In 1973, I evaluated a 44-year-old nurse who complained of severe attacks of chest pain, not necessarily related to activity. She had normal results on physical examination, electrocardiography, echocardiography, a maximal-effort stress test, and coronary arteriography. Dr. Earl Shirey was kind enough to overread an angiographic read performed by my colleague, Dr. Fred Heupler. They agreed that my patient had no evidence of coronary artery obstruction. I had an intuition that the patient had some abnormality of her coronary arteries. I admitted her to the coronary care unit for constant monitoring.

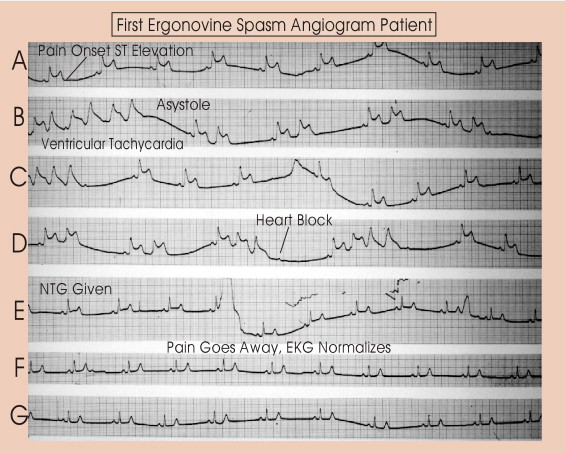

While in the unit, the patient suddenly developed a terrified look in her eyes. She said, “I’m starting to have an attack.” I then recorded the electrocardiogram shown in Figure 1 . I had reviewed her angiogram with Drs. Shirey and Heupler. She was starting to have what looked like an acute myocardial infarction, with normal coronary arteries! Within moments, her electrocardiogram showed complete heart block, and she was nearing a complete cardiac standstill. I placed nitroglycerin under her tongue, and within minutes, all signs and symptoms had resolved. Had I not recorded the electrocardiogram, the episode would not have been believed.

The patient proceeded to have several such attacks in the next 24 hours. Dr. Bill Proudfit (chief of clinical cardiology) and I then had in-depth discussions of this problem. We discussed the careful delineation of the syndrome caused by coronary artery spasm with the symptom termed “angina inversa” by Prinzmetal et al. We knew that earlier research had described this disorder, including the angiographic demonstration of coronary artery spasm. A reliable, reproducible, and safe provocative test for the Prinzmetal syndrome was needed.

It happened that Drs. Proudfit and Roy Lewis had provoked coronary artery spasm and narrowing in the 1960’s in the search for a good bedside stress test for coronary disease. Unfortunately, the drug they used, ergonovine, was alleged to cause acute myocardial infarction; the tests had been abandoned for that reason. There was no known antidote for this spasm-provoking drug.

I suggested the use of nitroprusside, a drug that Dr. Harriet Dustan was using in the Cleveland Clinic Research Division at that time to treat severe hypertension. Dr. Proudfit agreed with this idea, and we proceeded to administer a small dose of ergonovine to the patient, provoking an attack of chest pain with ST-segment elevation. The nitroprusside antidote reversed the signs and symptoms of coronary spasm within seconds. The patient then agreed to undergo repeat catheterization with an ergonovine test during coronary angiography. To our knowledge, this had not been done previously.

During repeat coronary angiography, ergonovine was infused. Within moments, the electrocardiogram showed marked ST elevation, and the patient began to have angina pectoris. Dr. Heupler started injecting contrast material and recording the event. He performed left and right coronary arteriography and left ventriculography in <5 minutes. He administered the antidote of nitroprusside, which turned her arteries from tightly spastic, with total right coronary artery occlusion, to large, baggy, veinlike structures. We watched in amazement, Dr. Proudfit and I together, as the patient’s right coronary artery went from normal to total obstruction in only a few moments and dilated beautifully with the nitroprusside infusion.

Dr. Mason Sones (chief of the cardiac catheterization laboratory) heard about this procedure. He and his colleagues Drs. Heupler and Shirey studied my patient’s angiograms carefully. Finally, Dr. Shirey said that he thought there was a slight irregularity of the right coronary artery, where the spasm had occurred. I was delighted with the success of our experiment and felt that we were again breaking new ground in the understanding of coronary artery disease.

Within 6 months, Dr. Heupler and I gathered data on patients with coronary artery spasm and nearly normal or normal coronary arteriographic results. We read our paper to the American Heart Association and published our abstract in Circulation . Pathologic studies revealed serious discrepancies between angiographic and anatomic evaluations.

In short order, Fred Heupler and associates at the Cleveland Clinic, as well as many other investigators, published numerous articles on this subject. Ergonovine and other substances were used to produce spasm, with various drugs (usually nitroglycerin) used to reverse the effect.

Such were the time and events surrounding the development of provocative testing for angiographic proof of the syndrome of coronary artery spasm and “angina inversa” described by Prinzmetal et al in 1959.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree