The Evaluation of Small Biopsies for Lung Cancer

Andre L. Moreira, M.D.

Background

The majority of patients with lung cancer present with advanced disease stage at diagnosis, and small biopsy including cytology is often the only specimen available for diagnosis. Because therapy for lung cancer is highly influenced by disease stage and tumor characteristics, the importance of small biopsy has grown significantly in patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) due to the shift to personalized therapy.1,2 The discoveries of activating mutations in pulmonary adenocarcinomas, and histology-based recommendation to chemotherapeutic drugs in NSCLC, brought many new challenges to pathologists who are now required to subclassify NSCLC in small biopsy material and triage for molecular tests.3,4,5

In response to this challenge, the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC), the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) joined force to reevaluate the histologic classification of lung cancer.6 The proposed changes by the IASLC/ERS/ATS now constitute the recommendations of the 2015 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of lung carcinomas.7

Tumor Classification in Small Biopsy and Cytology

Traditionally, there have been four major histologic types of lung cancer: small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell carcinoma; the latter three categories were often grouped as non-small cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) in biopsy specimens. Until the last decade or so, there was no need to further subclassify NSCLC, because all these entities were similarly managed clinically.

Squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma are practically the only histologic subtypes of NSCLC that can be diagnosed in small biopsy and cytologic specimens. The diagnosis of large cell carcinoma cannot be established with certainty in small biopsy material, because the entity is defined as a poorly differentiated carcinoma without histologic evidence of adenocarcinoma (gland formation) or squamous cell carcinoma (keratinization). Therefore, the diagnosis of large cell carcinoma still requires the examination of a resected tumor to exclude differentiation features.8 Small cell carcinoma and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma are often diagnosed in small biopsy.9,10,11

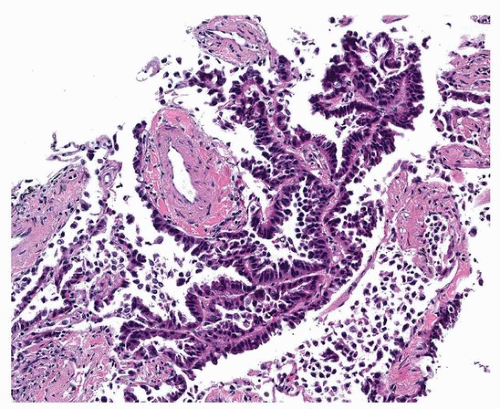

The criteria for the diagnosis of adenocarcinoma in a small biopsy are determined by the identification of specific histologic patterns such as lepidic, acinar, papillary, and micropapillary (Fig. 86.1). In biopsies where the only pattern present is lepidic, it is recommended that the nomenclature of “adenocarcinoma with lepidic pattern” be used. The reason for this recommendation is that a biopsy with only lepidic pattern may correspond in a subsequent excision to an adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (MIA), and a lepidic component of an invasive adenocarcinoma. AIS and MIA should not be diagnosed in a biopsy specimen. These two entities require examination of the entire tumor to exclude an invasive pattern, as well as lymphatic and pleural invasion. The presence of adenocarcinoma patterns in a small biopsy should be sufficient for the diagnosis without the need for further ancillary studies, unless metastatic disease is suspected.8,12

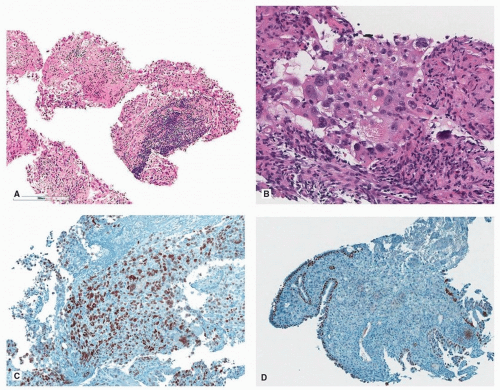

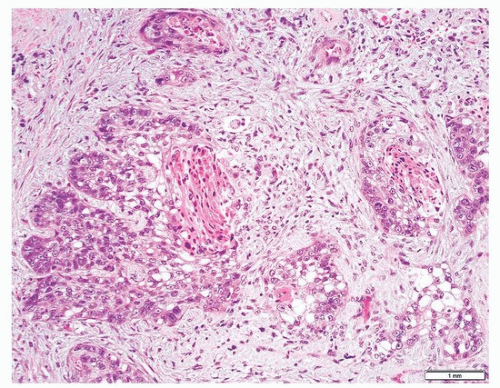

The two hallmarks for the diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma are keratinization and intercellular bridge (Fig. 86.2). Due to the number of advances in therapy for adenocarcinoma, a diagnosis of squamous cell carcinoma in a poorly differentiated NSCLC without proper documentation of squamous cell differentiation can potentially deprive a patient of appropriate and efficient therapy.

A tumor composed of solid pattern without any other histologic differentiating pattern should have evidence of differentiation confirmed by immunohistochemical stains (IHC). In cases of poorly differentiated NSCLC (nonkeratinizing squamous cell carcinoma or adenocarcinoma

with solid pattern), when IHC must be used for tumor classification, the current WHO classification recommends the use of the term NSCLC, followed by “favor adenocarcinoma,” when IHC favor glandular differentiation; NSCLC, favor squamous cell carcinoma, when the immunoprofile favors a squamous cell carcinoma; and NSCLC-not otherwise specified (NOS), when there is not enough material for IHC or the immunoprofile is equivocal (Fig. 86.3; Table 86.1).8

with solid pattern), when IHC must be used for tumor classification, the current WHO classification recommends the use of the term NSCLC, followed by “favor adenocarcinoma,” when IHC favor glandular differentiation; NSCLC, favor squamous cell carcinoma, when the immunoprofile favors a squamous cell carcinoma; and NSCLC-not otherwise specified (NOS), when there is not enough material for IHC or the immunoprofile is equivocal (Fig. 86.3; Table 86.1).8

FIGURE 86.2 ▲ Squamous cell carcinoma in an endobronchial biopsy. The presence of keratinization and intracellular bridges (not seen at this magnification) is diagnostic of this entity. |

One important pitfall of solid pattern in small biopsy is that a solidtype adenocarcinoma can show squamoid features such as nested appearance and glassy eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 86.3), although there is no clear keratinization or presence of intracellular bridges. This can be seen either on cytology or on small biopsy material and can be confused with squamous cell carcinoma. Knowledge of this pitfall can greatly reduce misclassification of NSCLC.

As demonstrated by Rekhtman et al.,13 a subclassification of NSCLC into adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma in cytology specimens can be achieved in ˜93% of the cases using cytomorphologic criteria only.13,14,15 However, the subclassification of NSCLC can be a problem in paucicellular specimens and in poorly differentiated carcinomas where no clear histologic differentiation is present. In these situations, morphologic features cannot make the distinction between adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma alone.

The histologic patterns of acinar, papillary, micropapillary, solid, and lepidic can be seen in small biopsy specimens but may be difficult to recognize in cytologic material.16,17,18 In the latter, a cell block preparation may be very helpful in identifying histologic patterns of adenocarcinoma that cannot be recognized on smears.16 In cytology, the determination of predominant type or subtyping of adenocarcinoma is not feasible.16,17,18,19 Rudomina et al. showed that the presence of acini structures in cytology preparations had a predictive value of 94% when correlated with the presence of acinar pattern in resection specimens.18 Acinar is the most common pattern in adenocarcinomas seen in resected specimens.20,21 However, the presence of papillary clusters with fibrovascular cores had a predictive value of 75%, and the presence of micropapillary tufts had a predictive value of 64% for micropapillary pattern on excised specimens. The authors found no cytologic features that correlated with solid pattern. Rodriguez et al. demonstrated that in ˜40% of cases, an acinar or papillary type can be attributed in cytology material, but there are no reliable cytomorphologic features that correlate with a solid or micropapillary type adenocarcinoma.17 The latter are important histologic patterns that are associated with poor prognosis. Therefore, as of the writing of this chapter, subtyping of adenocarcinomas in cytology materials is not recommended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree