This year marks the bicentennial of the invention of the stethoscope by René Théophile Hyacinthe Laennec in 1816, working at the Necker Hospital in Paris. Mediate auscultation was a logical evolution within French clinical empiricism that combined elucidated physical signs with autopsy correlation to provide diagnostic insight into diseases of the lungs and heart. Over the past 2 centuries, the stethoscope has brought the doctor and patient closer together, and it has become a fundamental tool in medical practice and the symbol of the clinician.

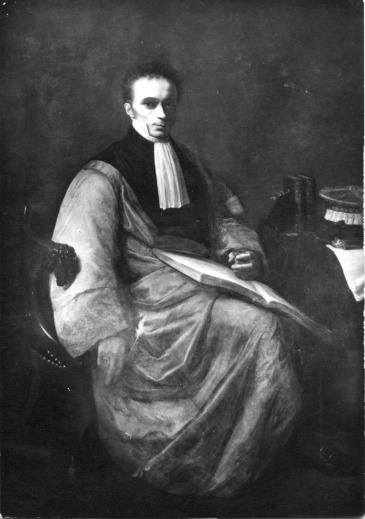

This year we celebrate the bicentennial of the invention of the stethoscope by René Théophile Hyacinthe Laennec ( Figure 1 ) and the introduction of mediate auscultation into clinical practice. “In 1816,” Laennec writes in the introduction to his classic text, here taken from the first English translation by John Forbes, “I was consulted by a young woman laboring under general symptoms of diseased heart and in whose case percussion and the application of the hand were of little avail on account of the great degree of fatness.” Recalling the “augmented impression of sound when conveyed through certain solid bodies—as when we hear the scratch of a pin at one end of a piece of wood, on applying our ear to the other,” Laennec rolled a quire of paper into a cylinder and placed it over the heart. With his ear to the other end, he found that he “could thereby perceive the action of the heart in a manner much more clear and distinct than I had ever been able to do by the immediate application of the ear,” and predicted that this method “might furnish means for enabling us to ascertain the character, not only of the action of the heart, but of every species of sound produced by the motion of all the thoracic viscera.” The paper roll was superseded by a solid wood cylinder that was about 1 foot in length and 2 inches in diameter, with a central bore that improved detection of the breath sounds. Laennec named the instrument the cylinder, or, the stethoscope.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree