Atrial fibrillation (AF) frequently coexists in the setting of myocardial infarction (MI), being associated with increased mortality. Nonetheless, temporal trends in the occurrence of AF complicating MI and in the prognosis of these patients are not well described. We examined temporal trends in prevalence of AF in the setting of MI and the effect of AF on prognosis in the community. We studied a population-based sample of 20,049 validated first-incident nonfatal hospitalized MIs among 35- to 74-year old residents of 4 communities in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study from 1987 through 2009. Prevalence of AF in the setting of MI increased from 11% to 15% during the 23-year study period. The multivariable adjusted odds ratio for prevalent AF, per 5-year increment, was 1.11 (95% confidence interval 1.04 to 1.19). Overall, in patients with MI, AF was associated with increased 1-year case fatality (odds ratio 1.47, 95% confidence interval 1.07 to 2.01) compared with those without AF. However, there was no evidence that the impact of AF on MI survival changed over time or differed over time by sex, race, or MI classification (all p values >0.10). In conclusion, co-occurrence of AF in MI slightly increased between 1987 and 2009. The adverse impact of AF on survival in the setting of MI was consistent throughout. In the setting of MI, co-occurrence of AF should be viewed as a critical clinical event, and treatment needs unique to this population should be explored further.

Despite the significant decline in the incidence rate of myocardial infarction (MI) since the end of the twentieth century, the estimated annual incidence of MI in the United States remains high at 525,000 cases. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis reported that approximately 1 in 10 MI patients had concomitant atrial fibrillation (AF), which was associated with a significantly increased risk of death. However, little is known about the temporal trends related to the association of AF with prognosis of MI patients. Two studies reported a significantly higher mortality rate among MI patients who developed AF compared with those who did not, with no evidence of a clinically meaningful improvement in survival during the study period among those with coexisting AF and MI. Both studies were relatively small and lacked precision in trend analyses. Furthermore, the previous studies on prognosis of patients with co-occurring AF and MI have been conducted in predominately white communities, which is a limitation because the decline in incidence and mortality rates for MI have been slower among blacks compared with whites, especially among men, and blacks have a lower risk of AF compared with whites. Our aims were to estimate the prevalence of AF in the setting of MI over time and by sex, race, and MI classification, to describe the impact of AF on mortality, and to assess the temporal trends in mortality among MI patients with and without concomitant AF overall and among subgroups using a large community-based biracial study.

Methods

The community surveillance component of the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study, described previously, was designed to provide knowledge about the burden of and trends in coronary heart disease (CHD) morbidity and mortality in 4 US communities (details included in the Supplementary Material ).

Presence of AF during the MI hospitalization was defined by the presence of AF International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM ), hospital discharge diagnosis codes of 427.3x in any position. Validity of ICD codes for the identification of AF has been described elsewhere. We did not distinguish between AF that started before versus during the MI hospitalization.

All-cause mortality, at 28 days and 1 year, was determined by medical record review, state death records linkage, and linkage with the National Death Index. Deaths were classified based on the duration from date of hospital admission until date of death.

Patient characteristics, including age, sex, and race, were abstracted from medical records by trained and certified study staff as were data on cardiovascular-related co-morbidities, including a history of hypertension, stroke, and diabetes. Prescription medications at admission, during hospitalization, or at discharge and procedures were classified as yes or no. New therapies have been introduced during the study period, and the impact of these therapies was estimated beginning in the year for which complete treatment information was available: ACE or angiotensin II inhibitors, 1992; antiplatelet agents other than aspirin, 1997; and lipid-lowering agents, 1999.

Adjustment for disease severity and clinical co-morbidities was performed with a modified Predicting Risk of Death in Cardiac Disease Tool (PREDICT) score. The PREDICT score, developed in a community-based study, uses information routinely collected during a hospitalization with MI, including cardiogenic shock, clinical history (cardiac events and procedures), age, severity of electrocardiographic changes, congestive HF, kidney function, and the Charlson Comorbidity Index, to determine mortality risk. Data on renal function have not always been collected in ARIC community surveillance, so a validated modification of the PREDICT score, ranging from 0 to 21, was used.

Hospitalized nonfatal first-incident definite and probable MIs were eligible for inclusion. Patients whose race was not white or black and nonwhites from the Minneapolis and Washington County field centers were excluded (n = 442) because of insufficient sample size. Patients with unknown mortality status at 28 days or 1 year (n = 342) or with incomplete covariate data (n = 91) were also excluded.

The temporal trend in prevalence of coexisting AF among MI patients was assessed with a logistic regression model using year (continuous) as the main independent variable adjusted for age (5-year groups), sex, a composite race and field center variable, number of ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes, MI classification (ST-elevation myocardial infarction [STEMI]/non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction [NSTEMI]/unclassified), and severity (PREDICT). The impact of AF on survival overall was assessed with logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, race, field center, MI classification, number of ICD-9-CM codes, severity (PREDICT), presentation characteristics (first systolic blood pressure and first pulse), medications, and therapeutic procedures and within subgroups defined by sex, race, and MI classification.

Trends in the association of AF with 1-year case fatality among MI patients were examined with multivariable logistic regression models. Prespecified 2-way multiplicative interactions of trends in prevalence and mortality with sex, race, and MI classification were examined. A p <0.10 was considered evidence of effect modification.

All analyses weighted the contribution of each hospitalization by the inverse of its sampling probability to generate point, variance, and 2-tailed p values that account for the sampling design. All statistical analyses were performed using survey procedures in SAS (version 9.2; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Our final analytic sample included 13,155 definite and probable first-incident MIs, for a weighted sample of 20,049. Baseline patient characteristics over time, in 4-year intervals, are listed in Table 1 , whereas Table 2 lists the prevalence of medications and therapeutic procedures. The age and sex distributions of the sample were stable over the study period, with an overall mean age of 59 years at the time of hospitalization; women accounted for 36% of the sample. The prevalence of AF accompanying MI increased slightly over the 23-year study period ( Table 1 ), although this was primarily because of a low prevalence of concomitant AF in the first few years. The proportion of MIs classified as NSTEMI increased during the study period.

| Variable | 1987–1990 (n = 3330) | 1991–1994 (n = 3735) | 1995–1998 (n = 3770) | 1999–2002 (n = 3501) | 2003–2006 (n = 3215) | 2007–2009 (n = 2499) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 59.8 | 59.9 | 59.6 | 59.0 | 58.9 | 58.8 |

| Women | 1140 (34%) | 1313 (35%) | 1380 (37%) | 1276 (36%) | 1144 (36%) | 955 (38%) |

| Community and race groups | ||||||

| Forsyth County, NC blacks | 271 (8%) | 325 (9%) | 459 (12%) | 364 (10%) | 369 (11%) | 420 (17%) |

| Forsyth County, NC whites | 966 (29%) | 1124 (30%) | 1174 (31%) | 975 (28%) | 899 (28%) | 763 (31%) |

| Jackson, MS blacks | 286 (9%) | 388 (10%) | 432 (11%) | 579 (17%) | 582 (18%) | 397 (16%) |

| Jackson, MS whites | 496 (15%) | 537 (14%) | 367 (10%) | 289 (8%) | 181 (6%) | 151 (6%) |

| Minneapolis, MN whites | 701 (21%) | 724 (19%) | 668 (18%) | 743 (21%) | 749 (23%) | 433 (17%) |

| Washington County, MD whites | 610 (18%) | 637 (17%) | 670 (18%) | 551 (16%) | 435 (14%) | 336 (13%) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| Hypertension | 1807 (54%) | 2138 (57%) | 2215 (59%) | 2240 (64%) | 2053 (64%) | 1855 (74%) |

| Stroke | 155 (5%) | 259 (7%) | 301 (8%) | 280 (8%) | 219 (7%) | 198 (8%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | — | 641 (17%) | 1076 (29%) | 1043 (30%) | 1139 (35%) | 946 (38%) |

| PREDICT score ∗ | 6.2 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5.7 | 5.7 | 6.8 |

| Presentation characteristics | ||||||

| Hospital arrival <2 hours † | 995 (30%) | 1113 (30%) | 1143 (30%) | 1064 (30%) | 798 (25%) | 623 (25%) |

| First systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 144.2 | 148.3 | 147.4 | 149.2 | 145.5 | 148.0 |

| First pulse rate (bpm) | 84.1 | 85.3 | 85.8 | 86.9 | 87.6 | 89.5 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 351 (11%) | 489 (13%) | 513 (14%) | 471 (13%) | 527 (16%) | 366 (15%) |

| Myocardial infarction classification | ||||||

| ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 793 (24%) | 1071 (29%) | 1038 (28%) | 689 (20%) | 512 (16%) | 517 (21%) |

| Non ST-elevation myocardial infarction | 2214 (66%) | 2157 (58%) | 2221 (59%) | 2373 (68%) | 2326 (72%) | 1789 (72%) |

| Unclassified | 323 (10%) | 506 (14%) | 510 (14%) | 438 (13%) | 377 (12%) | 194 (8%) |

∗ Modified PREDICT score did not include kidney function.

† Hospital arrival <2 hours was determined based on duration from earliest symptom onset time to hospital arrival time.

| Variable | 1987–1990 (n = 3330) | 1991–1994 (n = 3735) | 1995–1998 (n = 3770) | 1999–2002 (n = 3501) | 2003–2006 (n = 3215) | 2007–2009 (n = 2499) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication | ||||||

| Aspirin | 2251 (68%) | 3233 (87%) | 3358 (89%) | 3173 (91%) | 2846 (89%) | 2280 (91%) |

| β blockers | 1549 (47%) | 2252 (60%) | 2671 (71%) | 2832 (81%) | 2796 (87%) | 2236 (89%) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 2151 (65%) | 2197 (59%) | 1497 (40%) | 852 (24%) | 702 (22%) | 634 (25%) |

| ACE or angiotensin II inhibitors | — | 664 (18%) | 1724 (46%) | 2162 (62%) | 2115 (66%) | 1624 (65%) |

| Warfarin | 302 (9%) | 545 (15%) | 635 (17%) | 476 (14%) | 430 (13%) | 338 (14%) |

| Lipid-lowering medications | — | — | 248 (7%) | 2047 (58%) | 2284 (71%) | 1829 (73%) |

| Antiplatelet agents other than aspirin | — | — | 823 (22%) | 1992 (57%) | 2011 (63%) | 1504 (60%) |

| Procedure | ||||||

| Thrombolytic agents † | 737 (22%) | 998 (27%) | 708 (19%) | 366 (10%) | 52 (2%) | 52 (2%) |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 538 (16%) | 855 (23%) | 999 (27%) | 1202 (34%) | 1325 (41%) | 1020 (41%) |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 466 (14%) | 478 (13%) | 577 (15%) | 438 (13%) | 301 (9%) | 189 (8%) |

∗ On admission, during hospitalization, or at discharge.

† Thrombolytic agents include intracoronary and intravenous.

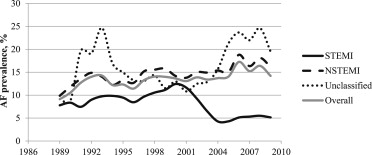

The prevalence of coexisting AF in the setting of MI increased over the study period. After adjustment, there was no evidence that the time trend in prevalence of co-occurring AF and MI differed by sex (p for interaction = 0.43) or race (p for interaction = 0.69); however, there was evidence of a different AF time trend by MI classification (p for interaction = 0.005) ( Figure 1 ). The prevalence of AF in patients with NSTEMI or unclassified MI (neither STEMI nor NSTEMI) increased during the study period, whereas among STEMI patients the prevalence of AF decreased.

Overall, the presence (vs absence) of AF complicating MI was associated with more than a twofold increased odds of post-MI death at 28 days and 1 year, after adjustment for age group, sex, race, field center, and year ( Table 3 ). This association did not differ by sex, race, or MI classification.

| Variable | Case Fatality (months) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 12 | |

| OR ∗ (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Number of deaths | 204 (1.0%) | 1431 (7.1%) |

| Model 1: Age, sex, race, field center and year | 2.23 (1.13–4.42) | 2.15 (1.63–2.83) |

| Model 2: Model 1 + MI classification † and # ICD-9-CM | 2.13 (1.06–4.29) | 1.93 (1.45–2.58) |

| Model 3: Model 2 + presentation characteristics ‡ | 1.92 (0.92–4.02) | 1.72 (1.26–2.35) |

| Model 4: Model 3 + Medication § | 2.20 (0.97–4.99) | 1.55 (1.12–2.12) |

| Model 5: Model 3 + therapeutic procedures ‖ | 1.71 (0.84–3.49) | 1.56 (1.15–2.12) |

| Model 6: Model 2 + presentation characteristics, medications and procedures | 2.10 (0.94–4.70) | 1.47 (1.07–2.01) |

∗ OR = odds ratio; comparison of co-occurring atrial fibrillation and myocardial infarction (MI) to MI.

† MI classification = ST-elevation MI, non ST-elevation MI and unclassified.

‡ Presentation characteristics = first systolic blood pressure, first pulse and the modified PREDICT score.

§ Medications = aspirin, β blockers, calcium channel blockers, ACE or angiotensin II inhibitors, warfarin, lipid-lowering medications and antiplatelet agents other than aspirin.

‖ Therapeutic procedures = percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass graft.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree