INDICATIONS

The rigidity of the chest wall makes it important for the thoracic surgeon to plan the surgical approach to the pleural space or mediastinum well. Thoracotomy incisions can be categorized by their location on the chest wall (anterior, lateral, and posterior), whether muscle is divided or preserved, and whether the sternum is divided, as in the hemiclamshell and clamshell approaches. Regardless of the size of the incision, it is important to plan the incision based on the location of structures that must be exposed. Even as more chest procedures are performed thoracoscopically, the minimally invasive chest surgeon must be proficient at various approaches to the lung and mediastinum. Thoracic surgeons must also be able to plan for emergency conversion from a thoracoscopic approach to a thoracotomy. Trauma surgeons must understand which thoracic incisions are useful for thoracic trauma especially when an intrathoracic subclavian artery injury is present. Finally, thoracic surgeons may be asked to provide access for spine surgery.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

A number of factors are important to selecting the type of thoracotomy incision.

Location and size of the tumor: An incision should primarily be planned to facilitate exposure to the region of interest. Other structures that may need to be accessed should be considered when planning the approach, such as vascular control (e.g., in superior sulcus tumors), intrapericardial control, access to the diaphragm (if plication is anticipated), etc.

Reoperative thoracotomy: In the setting of a reoperative thoracotomy an incision in a new location may be considered to avoid lung parenchymal adhesions. Alternatively, the same incision can be used, and a rib may be excised to facilitate exposure. When adhesions are anticipated, the incision should be planned, so that extension of the incision is easy to obtain additional exposure.

Body habitus: The patient’s body habitus should be considered when planning the type of thoracotomy incision. Excellent exposure may be obtained through a small anterolateral muscle-sparing thoracotomy in thin patients; however, exposure may be more challenging in muscular men. A latissimus dorsi-sparing posterolateral thoracotomy in an obese patient may lead to seroma formation from the extensive soft tissue mobilization necessary. Finally, debilitated patients who are mostly bed bound may have fewer local wound complications with a lateral or anterior approach as opposed to a posterolateral thoracotomy.

Anticipated use of muscle flap: The thoracic surgeon should anticipate whether a muscle flap might be necessary during this operation or future operations. Intercostal muscle flaps are most easily harvested through a posterolateral thoracotomy. The latissimus muscle can be preserved and mobilized as a flap through posterolateral thoracotomy when needed to fill a pleural space. The serratus anterior muscle is sometimes used to buttress a bronchial stump alone or in addition to intercostal muscle.

Size of incision: A thoracoscopic approach results in improved pain control postoperatively, and as a result decreased respiratory complications. It is tempting to extrapolate this observation to the comparison between large and small thoracotomies. However, there is insufficient data to conclude whether the length of a thoracotomy incision results in any difference in pain control, respiratory complications, or pulmonary function. Postthoracotomy pain arises in large part as a result of intercostal neuralgia, and this may be exacerbated by greater rib spreading needed for exposure when incisions are small.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Posterolateral Thoracotomy

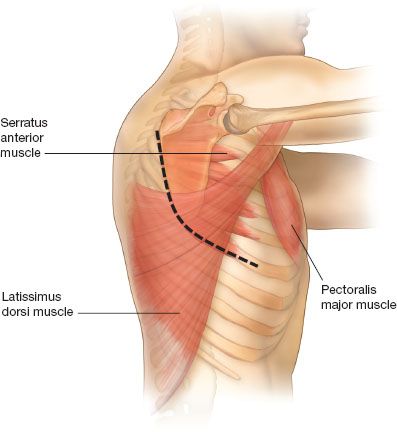

Posterolateral thoracotomy (Fig. 8.1) is the most commonly used and versatile incision for access to the hemithorax. This incision is commonly used for pulmonary surgery, extrapleural pneumonectomy, and access to the intrathoracic esophagus, trachea, and mainstem bronchi. Most surgeons do not divide the serratus anterior muscle to avoid postoperative shoulder dysfunction. While many surgeons divide the latissimus dorsi muscle, especially for large thoracotomy incisions, the latissimus may be mobilized and retracted. This leaves open the option of future latissimus muscle flap transfer to manage an infected pleural space or bronchopleural fistula.

Figure 8.1 Posterolateral thoracotomy: An incision is made 1 to 2 cm below the scapular tip and continued anteriorly along the direction of the rib and posteriorly between the scapula and the spine. The latissimus dorsi is either divided or preserved and the serratus muscle is retracted anteriorly.

The patient is positioned in a lateral decubitus position and the bed is flexed, so that the hip is out of the field and the rib interspaces widened. An axillary roll is used by most surgeons to protect the brachial plexus although the need for this is questionable as some surgeons do not use an axillary roll and report no untoward consequences. The incision is centered 1 or 2 cm under the scapular tip and extended anteriorly along the rib and posteriorly at the midpoint between the medial border of the scapula and the spine. The latissimus dorsi muscle is either mobilized and preserved or divided for additional access. If the latissimus is divided, it is often helpful to mobilize it off the serratus and overlying soft tissue for ease of later closure. The serratus can usually be spared and retracted medially. The paraspinous ligament is preserved and mobilized off of the rib interspace to be entered. The trapezius and rhomboid muscles can be divided posteriorly when the incision must curve high along the scapula, such as in superior sulcus resections. The scapula is then retracted and the ribs counted. The chest is entered in the fifth interspace for pulmonary resections. Depending on the operation, one may then enter the pleural space by incising the intercostal muscle along the top of the rib, harvesting an intercostal muscle flap, or resecting a rib.

When harvesting an intercostal muscle flap, a periosteal elevator is the most effective way to harvest the muscle in the subperiosteal plane. The ribs above and below the intercostal muscle are scored and the periosteum is scraped toward the muscle. The elevator is then used to free the muscle off of the rib below and above the muscle, and then the pleura is incised to separate the muscle. This technique may result in ossification of the muscle flap with time because it leaves periosteum on the muscle, but this almost never causes a problem. Some surgeons use electrocautery to harvest the muscle flap to avoid taking the periosteum with the flap.

The rib may be shingled posteriorly at the level of the paraspinous ligament using a sliding rib cutter to prevent uncontrolled fracture of the ribs with retraction. A rib may be resected in certain circumstances such as when there is extensive pleural disease or extensive adhesions. A periosteal elevator is used to free the rib from the intercostal muscles after scoring and scraping the pleura off the bone after which the bone is resected with a rib cutter.

Once the chest retractor is inserted, the intercostal muscle beyond the incision is freed along the rib anteriorly with a freer or using electrocautery. For closure, pericostal sutures can be placed around the ribs or holes can be drilled in the inferior rib, so that the suture does not put pressure on the intercostal nerve. When a rib is resected, the intercostal muscles are reapproximated with interrupted 0-silk sutures and a rib approximator is used while tying down the sutures. The latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles are then reapproximated.

Anterolateral Thoracotomy

Anterolateral thoracotomy (or “French” incision) (Fig. 8.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree