Chapter 42 Takayasu’s Arteritis

Epidemiology

Takayasu’s arteritis is a rare disorder that has variable incidence and prevalence depending on the country where it has been studied. In the United States, incidence estimates from Olmstead County, Minnesota, are 2.6 cases/million/yr, whereas in Sweden they are 1.2 cases/million/yr.1,2 Autopsy studies in Japan document a high prevalence, with evidence of Takayasu’s arteritis found in 1 of every 3000 individuals.3 Similar postmortem studies have not been performed elsewhere to provide comparative data.

Pathogenesis

Differences in disease prevalence and characteristics among different racial and ethnic cohorts suggest a genetic predisposition; however, no definite allelic associations have been found consistently across all groups of patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. The well-established association between certain infections and secondary vasculitis has propelled a search for an infectious etiology. Special attention has been directed toward mycobacterial pathogens because of the increased prevalence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (TB) infection in countries (e.g., India, Korea, Mexico) with a high prevalence of Takayasu’s arteritis, associations of Takayasu’s arteritis with previous mycobacterial infection, and TB skin test positivity in patients with Takayasu’s arteritis. In several small studies, patients with Takayasu’s arteritis were demonstrated to have increased immunological responses to mycobacterial proteins when compared to healthy controls, but these inflammatory responses can be nonspecific and do not prove causality.4,5

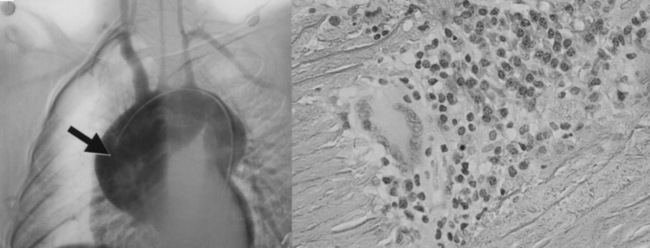

Vessel injury results from the influx and actions of macrophages, cytotoxic T cells, γδT cells, natural killer cells,6 and B cells. Access of leukocytes to the vessel wall is through the vasa vasorum, with subsequent migration toward the large lumen intima. Various cytokines, including perforin, interleukin (IL)-6, RANTES (regulated, upon activation, normal T-cell expressed, and secreted), tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α,7,8 and B-cell activating factor (BAFF),9 enhance vascular inflammation. Although the most common response to this process is myointimal proliferation that leads to wall thickening and luminal stenosis, destruction of smooth muscle cells (SMCs), elastic fibers, and other matrix proteins may lead to aneurysm formation, especially in the aortic root and arch (Fig. 42-1). Disease progression leads to secondary vessel stiffening associated with atherosclerosis.10

Clinical Manifestations

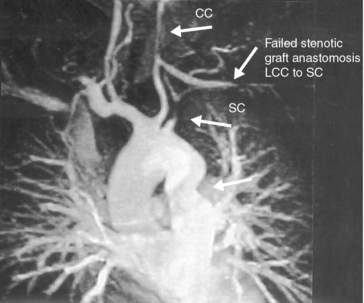

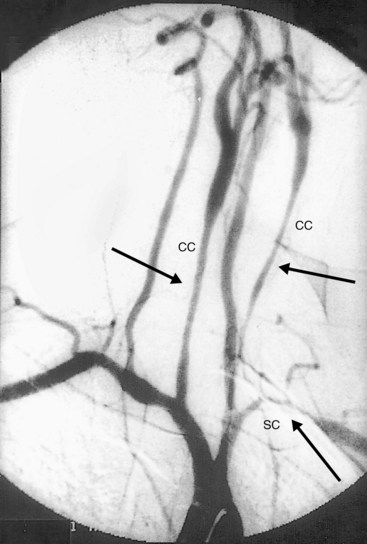

Systemic symptoms and signs occur in less than half of all patients and include fever, weight loss, malaise, and generalized arthralgias and myalgias. Patients more often present with signs and/or symptoms of tissue ischemia, never having had an associated systemic illness. The most common symptom of Takayasu’s arteritis is upper-extremity claudication, occurring in more than 60% of patients and reflecting disease predilection for aortic arch vessels (≈︀90% of cases)11 (Figs. 42-2 through 42-4). The most frequent clinical findings include blood pressure asymmetry in paired extremities, and bruits found most often over the carotid, subclavian, and aortic vessels.12 Aneurysms most often affect the aortic root, stretching the atrioventricular annulus and producing valvular regurgitation (≈︀20% of patients); valve leaflets are not a site of inflammation. Many within this subset require surgical intervention.

Figure 42-3 Angiography demonstrating stenoses of left subclavian (SC) and bilateral common carotid (CC) arteries.

Hypertension occurs in at least 40% of patients in U.S. cohorts and is even more common in Japanese and Indian cohorts (80%). Hypertension is most frequently due to renal artery stenosis (RAS), but it may also result from suprarenal aortic stenosis or loss of aortic compliance11,13 (Figs. 42-5 through 42-7). The diagnosis of hypertension can easily be missed in patients with disease involving both upper extremities, where peripheral cuff measurements in either arm will be an inaccurate reflection of central aortic pressure. Hypertension with vascular bruits or claudication, especially in younger patients, should lead to a suspicion of Takayasu’s arteritis and to further evaluation of all four extremity pulses and blood pressures for asymmetry. Vascular imaging of the entire aorta and primary branch vessels should then confirm anatomical abnormalities compatible with the diagnosis and delineate the extent of disease and types of lesions.

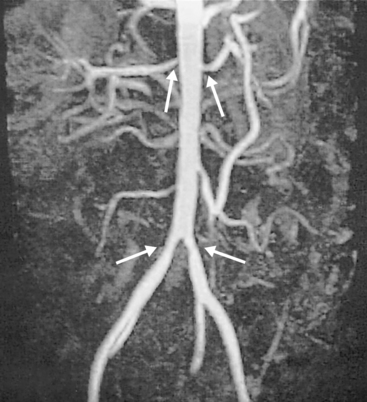

Figure 42-5 Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) showing bilateral common iliac and renal arterial stenoses.

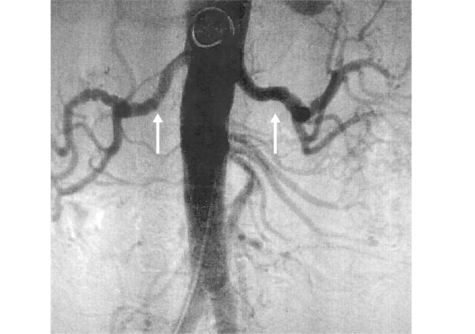

Figure 42-6 Angiography demonstrating bilateral renal artery lesions mimicking fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD).

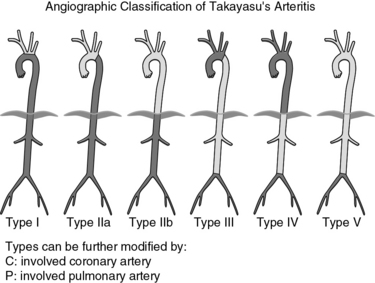

Classification of Takayasu’s arteritis is based on sites of arterial involvement. One of the most widely accepted schemes separates patients into the following types (Fig. 42-8):

• Type I: branches of the aortic arch.

• Type IIa: ascending aorta, aortic arch, and its branches.

• Type IIb: type IIa plus thoracic descending aorta.

• Type III: thoracic descending aorta, abdominal aorta, or renal arteries, or a combination.

• Type IV: only abdominal aorta or renal arteries, or both.

Morbidity results primarily from extremity claudication, less often from cardiac, renal, and central nervous system (CNS) vascular disease. Undetected and/or untreated hypertension is a significant cofactor in these disease sequelae. Mortality estimates range from just 3% at 8 years to 35% at 5 years’ follow-up. Causes of death include stroke, congestive heart failure, sudden death of uncertain cause, and unrecognized or inadequately treated hypertension.14,15

Differential Diagnosis

A thorough and careful investigation is necessary to distinguish Takayasu’s arteritis from its mimics (Box 42-1). Congenital and acquired disorders of tissue matrix may present with aortic root diltation, valvular insufficiency, and aneurysms in other sites; however, they are not generally associated with large-vessel stenoses, the hallmark of Takayasu’s arteritis. In many cases, there are also genetic studies and extravascular features that help identify the syndromic disorders (e.g., Marfan, Loeys-Dietz, Ehlers-Danlos syndromes). Exceptions better known for matrix abnormalities usually leading to stenoses are fibromuscular dysplasia and Grange’s syndrome.16

![]() Box 42-1 Differential Diagnosis of Takayasu’s Arteritis

Box 42-1 Differential Diagnosis of Takayasu’s Arteritis

Autoimmune Disease

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)*

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis*

Immunoglobulin (Ig)G4 systemic disease with aortitis

Idiopathic single-organ vasculitis restricted to the aortic arch

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree