Raynaud’s phenomenon

Dysmenorrhea

Glaucoma

Acrocyanosis

Pancreatitis

Perniosis

Buerger’s disease

Angina pectoris

Arteriosclerosis

Causalgia

Arrhythmias

Hirschsprung’s disease

Migraine

Poliomyelitis

Arthritis

Renal disorders

Hyperhidrosis

Retinitis pigmentosa

Gall bladder disease

Paget’s disease of bone

Venous ulcerations

Peptic ulcer

Epilepsy

Constipation

Nowadays, thoracoscopic sympathectomy is indicated for a limited number of applications (Table 19.2).

Table 19.2

Current indications for thoracoscopic sympathectomy

1. Universally accepted: |

Essential hyperhidrosis (palmar, axillar, facial) |

Facial blushing/social phobia syndrome |

2. In selected cases: |

Raynaud’s phenomenon, acrocyanosis, upper limb arterial insufficiency |

Buerger’s disease |

Causalgia |

Angina pectoris, long QT syndrome, ventricular and arterial tachycardia |

Chronic pancreatic pain (pancreatic carcinoma, chronic pancreatitis) |

Essential hyperhidrosis, characterized by pathological sweating of the hand and/or armpits, is the main indication for TTS, both in adults (Noppen 2004; Krasna 2008) and children and adolescents (Noppen et al. 1998 b; Steiner et al. 2008). It is generally believed that patients with essential hyperhidrosis should have completed a trial of nonoperative treatment prior to sympathectomy; these trials include topical agents containing aluminum chloride or hexahydrate, oral agents (anticholinergics, beta-blockers, and antidepressants), locally applied botulinum toxin, iontophoresis, and psychotherapy. However, results of these nonsurgical trials are often disappointing in the long term because of poor efficacy, occurrence of side effects, temporary response, and cost. Recent studies comparing medical to thoracoscopic management have shown that thoracoscopic sympathectomy is superior to medical management in terms of clinical outcome and side effects. Therefore thoracoscopic sympathectomy should be recommended as first-line treatment rather than a “last resort,” especially for the typical, severe form of essential palmar and axillary hyperhidrosis (Baumgartner et al. 2009; Ambrogi et al. 2009).

Facial blushing/social phobia (Fig. 19.1) is another possible variant of hypersympathicotony and may also be associated with facial hyperhidrosis. It sometimes presents with extremely disabling effects which has occasionally led to suicide. In these patients, an approach using a combination of medical interventions including daily low-dose anticholinergic (glycopyrrolate), a beta-blocker (propranolol), a central alpha-agonist (clonidine), and an anxiolytic (alprazolam) is often successful (unpublished data). In patients with significant side effects, or when a definitive treatment is requested by the patient, a thoracoscopic sympathectomy can be performed (Neumayer et al. 2005; Drott et al. 1998).

Fig. 19.1

A patient with facial flushing before (left) and after (right) a T2 thoracoscopic sympatholysis procedure

In Raynaud’s phenomenon, acrocyanosis, and idiopathic thoracic outlet syndrome, thoracoscopic sympathectomy can provide temporary symptomatic benefit (Di Lorenzo et al. 1998; Sayers et al. 1994). However on occasions the effects can sometimes be longstanding. However, no large-scale controlled studies are available. Nevertheless, numerous case series suggest potential short and intermediate-term benefits as long as patients are carefully selected.

Thoracoscopic sympathectomy can be considered a reasonable alternative for cases of severe refractory Raynaud’s phenomenon (e.g., digital pre-gangrene; Fig. 19.2) as long as patients are well informed and accept a high probability of recurrent disease. However this approach is difficult to justify in cases with less severe disease. Thoracoscopic sympathectomy offers immediate relief in up to 65–90 % of cases; however, the recurrence rates are high, and symptoms will recur in more than half of patients within 1–4 years.

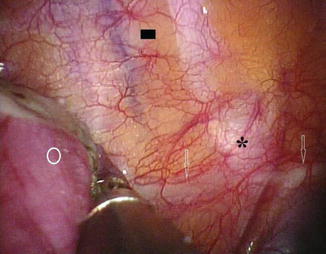

Fig. 19.2

An example of a pre-gangrenous lesion in a patient with Raynaud’s disease prior to a T2–T3 thoracoscopic sympatholysis

The effects of TTS appear to be very short-lasting in patients with Buerger’s disease, especially if the subject continues to smoke. However in rare highly selected cases of upper limb arterial insufficiency associated with Buerger’s disease, we have observed significant symptomatic improvements and significant delay in time to amputation (personal observations).

Thoracoscopic sympathectomy has been – and still is – used in the treatment of causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy. The success rates are reported to be above 90 % in selected cases with refractory disease and successful sympathetic block (Mockus et al. 1987). However, the role of the sympathetic nervous system in causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy has recently been questioned. There is little evidence that interrupting the sympathetic supply is more effective in alleviating the pain of causalgia and reflex sympathetic dystrophy when compared to placebo (Schott 1998).

Some series also suggest a potential role of TTS in the treatment of a variety of cardiac disorders, such as severe angina pectoris refractory to medical or surgical treatment (Wettervik et al. 1995) and various arrhythmias including long QT syndrome (Moss et al. 1985) and ventricular and paroxysmal atrial tachycardia (Kadowaki and Levett 1986).

Finally, lower sympathetic interruption has been demonstrated to be beneficial in the treatment of chronic pancreatic pain with significant pain relief in 64–100 % of patients (Noppen et al. 1998a, b).

All levels of sympathetic interruption can safely be performed by thoracoscopic sympathicolysis when performed by a trained pulmonologist.

19.2.2 Contraindications

Thoracoscopic sympathectomy, like any other thoracoscopic procedure, requires the presence of an open pleural space: small pleural adhesions, which may be encountered apically, especially in elderly patients, can often be easily transected. However the presence of extensive, organized pleural adhesions (e.g., after pleurodesis or as a post infectious sequelae) may compromise thoracoscopic interventions.

Refractory bleeding diathesis is another general contraindication to thoracoscopic sympathectomy.

19.3 Equipment

Although virtually all medical thoracoscopic interventions can safely be performed in a dedicated endoscopy suite (Boutin et al. 1991), we prefer to use a fully equipped operating theater for safety, logistical, and staff reasons. Whereas diagnostic thoracoscopies are often performed under local anaesthesia and intravenous sedation, interventional “red zone” medical thoracoscopies (e.g., for thoracoscopic sympathicolysis) are usually performed using total intravenous anaesthesia and single-lumen intubation with high-frequency jet ventilation (D’Haese et al. 1996).

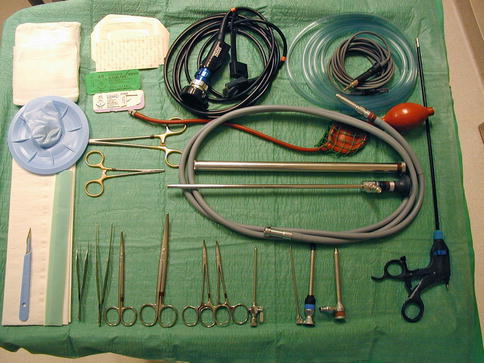

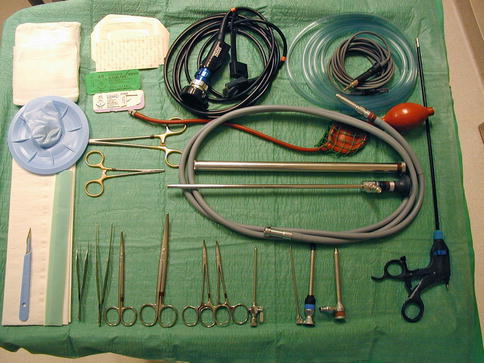

With regard to the necessary required equipment, a “simple” medical thoracoscopy set is sufficient (Fig. 19.3). Video assistance is obtained by means of a dedicated video camera and TV display. Sympathetic ablation is easily achieved by means of a coagulation forceps heated by a unipolar electrocoagulation unit. No chest drains are needed.

Fig. 19.3

A standard rigid “medical thoracoscopy” set as used for thoracoscopic sympatholysis

The total cost of the (multiple-use) medical thoracoscopy equipment and video display is estimated at 10,000 USD. In our institution (with about 100 thoracoscopic interventions per year), the telescopes are renewed every 5 years, and the video camera and imaging and data storage facilities need to be replaced every 5–10 years.

19.4 The Level of Interruption for Thoracoscopic Sympathectomy

Segmental postganglionic fibers synapsing in the paravertebral lower cervical and thoracic sympathetic ganglia (which form the sympathetic chain) provide the sympathetic innervation for a variety of internal organs (the heart, lungs, and intestine including the pancreas) and blood vessels and sweat glands of the face and neck, upper limb, and axillary region. Thoracoscopic sympathectomy is performed at the segmental level(s) relevant to the required effect of denervation (Table 19.3). The eighth cervical ganglion and the first thoracic ganglion are often fused together, forming the stellate ganglion; this lies over the neck of the first rib in both hemithoraces. Ablation of the stellate ganglion, which supplies the sympathetic innervation of the face and neck, should be avoided because of the associated risk for developing a Horner’s syndrome.

Table 19.3

Level of sympathetic denervation in function of the indication

Indication | Sympathectomy level |

|---|---|

Facial blushing and sweating | T2 |

Palmar hyperhidrosis | T3 |

Axillar hyperhidrosis | T4 |

Upper limb vasospastic disorders; causalgia | T2–T3 |

Cardiac disorders | Lower T1–T6 (T10) |

Pancreatic denervation | T5–T11 |

Each rib caudal to the first rib has its corresponding ganglion, although there is a great anatomical variability.

The T2 ganglion is the primary source of sympathetic innervation of the face and the hands, although more extensive ablation (T2–T3, T2–T4, even up to T2–T6) has been used in the past for the treatment of palmar hyperhidrosis. However, the success rate is identical when only the T2 ganglion is ablated for this condition (Kao 1992; Lin 1992). Limiting the number of levels ablated appears to reduce the extent and severity of side effects, e.g., compensatory hyperhidrosis (Gossot et al. 1997). Our personal experience together with recent published data demonstrates that successful management of palmar sweating can be obtained by T3 sympathectomy (Fig. 19.4), with a lower associated incidence of compensatory sweating (Sciuchetti et al. 2008), and indeed some authors now even “descend” towards T4 for palmar hyperhidrosis (Wolosker et al. 2008).