Viskum and Enk (1981)

Revision of 2,298 reported procedures in 15 (general) series

Subcutaneous emphysema: 1.3 %

Empyema: 2 %

(Significant) bleeding: 2.3 %

Air embolism: 0.2 %

Death due to the technique: 0.09 %

Viallat et al. (1996) (360 patients undergoing talc poudrage)

Subcutaneous emphysema: 0.6 %

Empyema: 2.5 %

Ribas et al. (2001) (614 patients undergoing talc poudrage)

Empyema: 2.7 %

Re-expansion pulmonary oedema: 2.2 %

Respiratory failure: 1.3 %

Air leak: 0.5 %

Postoperative bleeding: 0.4 %

Colt (2005) (52 prospective procedures)

Major adverse event: 1.92 % (1/52) [This was a patient with severe dyspnea, advanced scleroderma and recurrent pleural effusion who underwent a thoracoscopy for drainage and assessment of lung expansibility. A severely trapped lung was observed, so pleurodesis was not performed. Symptoms resolved after drainage with a small-bore chest tube]

No procedure-related deaths or intraoperative accidents

No patient required immediate open-chest surgery

There were no episodes of procedure-related sepsis, prolonged intubation or prolonged air leak requiring re-intervention or thoracotomy

Thoracoscopy was never aborted due to failure of entry into the pleural space (extended thoracoscopy was performed in two patients with empyema)

Minor adverse events: 19.2 % (10/52) including talc-related fever in 7 subjects. This adverse rate decreased to 5.7 % (3/52) if talc-related fever removed from the analysis [These included wound infection at a chest tube insertion site (1), fever (1) and a small clinically insignificant pneumothorax after chest tube removal]

Table 22.2

Complications of thoracoscopy in patients with malignant pleural effusion undergoing talc poudrage using two different types of talc (personal experience)

Complications | Patients (N = 512) | Small-particle talc (N = 232) | Large-particle talc (N = 280) |

|---|---|---|---|

Death < 10 days N = 26/232 (11 %) | Death < 10 days N = 5/280 (1.8 %) | ||

Transient dyspnea after talc | 50 (9.8 %) | 31 (13.4 %) | 19 (6.8 %) |

Acute pain after talc | 44 (8.6 %) | 28 (12 %) | 16 (5.7 %) |

Subcutaneous emphysema | 20 (3.9 %) | 16 (6.9 %) | 4 (1.4 %) |

Neoplastic invasion of the thoracoscopy tract | 14 (2.7 %) | 12 (5.2 %) | 2 (0.7 %) |

Pulmonary embolism | 12 (2.3 %) | 9 (3.9 %) | 3 (1 %) |

Empyema | 9 (1.9 %) | 4 (1.7 %) | 5 (1.8 %) |

Bleeding (requiring blood transfusion) | 2 (0.4 %) | 1 (0.5 %) | 1 (0.4 %) |

Acute respiratory distress | 1 (0.2 %) | 1 (0.5 %) | – |

In order to understand better how to manage thoracoscopic complications, we are separating them into several categories:

22.2.1 Complications of Thoracoscopy Associated with Poor Patient Selection

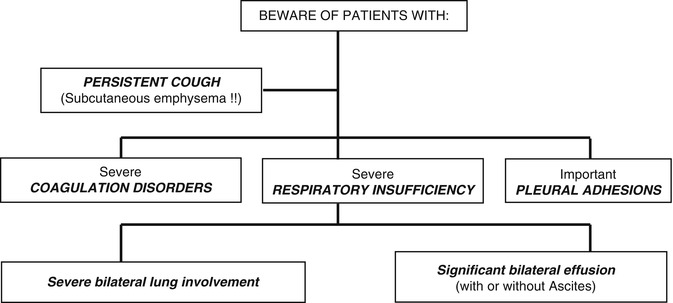

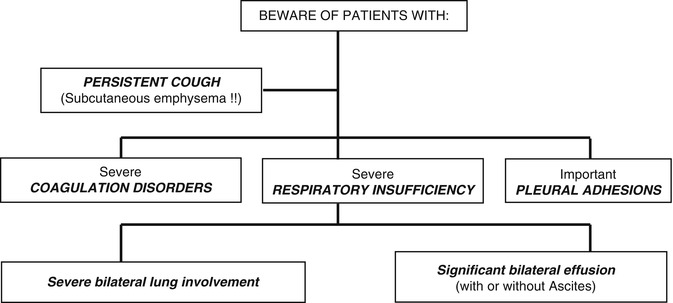

Most complications can be avoided by proper selection of patients for thoracoscopy (see Table 22.3 and Fig. 22.1). Patients with severe COPD and respiratory insufficiency – with hypoxemia (PO2 < 50 mmHg) and hypercapnia – will not tolerate the induction of a pneumothorax without a further deterioration of the gas exchange, and should be viewed as unsuitable candidates for thoracoscopy. When there is severe contralateral lung or pleural involvement, thoracoscopy is not advisable, unless general anaesthesia and tracheal intubation are used. Patients with unstable cardiovascular status should not undergo thoracoscopy: any patient with a history of cardiovascular disease – especially those with unstable angina or recent history of myocardial infarction – should be carefully evaluated before undertaking a thoracoscopy. Cough, fever and infection are relative contraindications to thoracoscopy, and definitive treatment or optimisation of these pre-existing conditions should be considered before a procedure is scheduled. Thoracoscopy is not feasible in the setting of tight adhesions between the visceral and the parietal pleura. In cases of localised pleural adhesions, it might be possible to create a pleural space by extended thoracoscopy using digital dissection in the pleural cavity (Janssen and Boutin 1992). However, this technique should be performed only by experienced thoracoscopists. Medical thoracoscopy is not safe in advanced pulmonary fibrosis; after induction of pneumothorax in these cases, severe acute hypoxemia might occur, and re-expansion of the lung can be difficult due to the loss of elasticity of the pulmonary tissue. In addition, biopsy of the lung parenchyma in pulmonary fibrosis may result in prolonged air leakage. Biopsy should also be avoided in hydatid cyst disease, arteriovenous malformations and other highly vascularised lesions.

Table 22.3

Patient selection criteria for thoracoscopy is critical, in order to prevent complications. In patient A, a contralateral lesion is seen in the lung parenchyma, and medical thoracoscopy (using conscious sedation and spontaneous ventilation) would be problematic. Patient B has a bilateral pleural effusion, and therapeutic thoracentesis in one side should be performed before attempting thoracoscopy on the contralateral side

Fig. 22.1

Patient A – a contralateral lesion is seen in the lung parenchyma, and medical thoracoscopy (under conscious sedation and spontaneous ventilation) would be problematic. Patient B – a patient with bilateral pleural effusions. In this scenario a therapeutic thoracentesis is required on one side prior to attempting thoracoscopy on the contralateral side

22.2.1.1 Pain and Anxiety

Pain and anxiety are frequent during the procedure – especially when the thoracoscopy is performed under local anaesthesia, even if talc poudrage is not performed. Although medical thoracoscopy is safe and relatively simple, this depends on the experience of the physician. In addition the operator needs to understand the cavity anatomy from the thoracoscopic point of view (which is not always the same as the conventional anatomy, as there is a limited field of vision compared with open thoracotomy or autopsy). The presence of multiple loculations can also make the exploration difficult. The technique should be explained clearly to the patient, especially when the procedure is going to be done under local anaesthesia, as this will allay the patients’ fears and make them more confident and relaxed during the exploration. The role of preoperative medication has not been subjected to randomised studies: we routinely administer 0.4–0.8 mg atropine (intramuscular or subcutaneous) prior to the procedure, to prevent vasovagal reactions. Intravenous midazolam can be very useful, especially in young patients. Sedation during the procedure can be performed using incremental dosages of a narcotic (morphine, pethidine or fentanyl) and a benzodiazepine, and agents to antagonise both morphine and benzodiazepine should be available. A number of considerations should be taken into account when choosing the anaesthetic technique:

Mental status of the patient (patients afraid of any medical procedure should be offered general anaesthesia; children and mentally retarded patients should be treated under general anaesthesia).

Suspected duration and type of thoracoscopy: when a procedure is suspected to be long or painful (e.g. multiloculated empyema), general anaesthesia is preferred. Procedures with two or more ports of entry, or those including chemical pleurodesis, are potentially more painful, and generous amounts of opiates may be required. We titrate intravenous pethidine while keeping the patient awake – and have obtained good results in more than 500 local anaesthesia procedures undergoing talc poudrage.

22.2.1.2 Acute Respiratory Insufficiency or Heart Failure

A posteroanterior and lateral chest X-ray film is mandatory in order to evaluate the most convenient port of entry, to exclude the presence of contralateral pulmonary lesions (that could lead to acute respiratory insufficiency at the time of inducing the pneumothorax for thoracoscopy) and to evaluate the size and shape of the pleural effusion. Electrocardiogram, coagulation and blood gas analysis are also necessary.

22.2.1.3 Other Complications Associated with Patient Selection

Great care is required with patients who are in a very poor clinical condition, hypoproteinemic or with diffuse neoplastic infiltration of the chest wall (Rodriguez Panadero 1995). In addition, medical thoracoscopy should be deferred in patients with an uncontrolled cough, because the exploration is likely to be difficult and results in more complications especially subcutaneous emphysema. Preoperative preparation of patients with obstructive lung disease should include chest physiotherapy, bronchodilators, antibiotics and corticosteroids.

In order to prevent pulmonary embolism, especially in patients with malignant pleural effusions treated with talc pleurodesis, we advise prophylactic heparin throughout the whole hospital stay.

22.2.2 Complications Associated with the Thoracoscopy Technique

22.2.2.1 Laceration of the Lung During Insertion of the Trocar

Some authors advocate the creation of a pneumothorax a few hours or even the day before the thoracoscopy. This technique may help reduce blood flow in the periphery of the lung, and may prevent damage to the lung after the introduction of the thoracoscopy instruments. However, direct introduction of a blunt trocar into the thoracic wall without prior induction of pneumothorax is, in our experience, safe and effective especially if there is enough pleural fluid. A previously induced pneumothorax can be useful to assess for pleural lesions and lung collapsibility in advance of a thoracoscopy, but a contrast CT scan, which is strongly recommended in the evaluation of every undiagnosed exudative pleural effusion, can also be very useful. Ultrasound examination can be also very helpful to identify loculations in the pleural cavity and to locate the best entry site for thoracoscopy (Tsai and Yang 2003; Medford 2010). The trocar should always be inserted perpendicular to the chest wall with a rotating/corkscrewing motion (see Fig. 22.2). It is safer to locate the tip over the border of the inferior rib at the chosen port of entry, in order to prevent damage to the intercostal vessels and nerves. Rarely the introduction of the trocar can be troublesome especially in cases of pleural adhesions. When the physician is not sure about the presence of tight adhesions between the lung and the chest wall at the chosen site of entry, a digital dissection and direct exploration of the port of entry with the telescope may be of help.

Fig. 22.2

Recommended technique for insertion of the trocar at thoracoscopy: – Apply firm pressure over the trocar with a rotating motion – Always keep the trocar vertical (perpendicular to the chest wall) – Use your other hand as a “brake”, to prevent laceration of the underlying lung with the trocar (by a sudden loss of resistance when the trocar passes through the pleura)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree