Most infected AAAs are symptomatic, but the onset is often insidious, with nonspecific symptoms and signs, and the correct diagnosis is often not made until the late stages of the disease, when sepsis and rupture have occurred. Overall, rupture has occurred in 50% to 85% of reported cases. Abdominal or back pain is present in most patients (up to 90%), but the classically described manifestations of fever, pain, and leukocytosis in the presence of an abdominal aneurysm occur together in less than 50% of cases. In one series, the interval between onset of symptoms and diagnosis averaged 38 days. Many patients have had a recent infection and have been treated with antibiotics during this interval, which might explain the common absence of signs of sepsis, negative blood and tissue cultures (50%), and unimpressive laboratory values.

The typical patient is older, has atherosclerosis, and initially comes to the hospital with low-grade fever, although chills and fever ultimately occur in about 70% of cases. The white blood cell count and other markers of inflammation are often elevated but are nonspecific. In one series, only 53% of patients had a leukocytosis of greater than 12,000. The presence of a palpable abdominal mass depends on the size and location of the aneurysm and the patient’s body habitus. Some patients have a history of bacteremia, but blood cultures might or might not be positive. Diabetes, corticosteroid use, and other immunocompromising conditions are commonly present. A history of arterial trauma, such as catheterization, can be an important diagnostic clue.

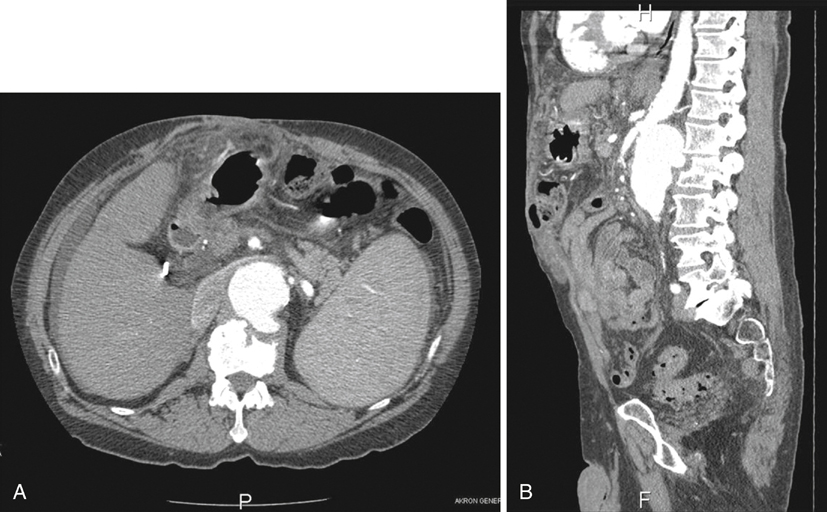

Definitive diagnosis of an infected AAA requires abdominal imaging, most commonly computed tomography (CT) scanning. CT findings strongly suggesting infected aneurysm include an irregular aortic wall, saccular or multilobular shape, unusual location (perivisceral aorta), and perivascular gas, especially when the rest of the aorta is relatively normal (Figure 1). Nonvascular findings include periaortic soft tissue mass, fat stranding and/or fluid, swollen psoas muscle (abscess), and vertebral body abnormalities (Figure 2). If more than one CT scan has been performed, rapid enlargement of the aneurysm is highly suspicious for an infectious etiology. There are few reports about the use of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), but aneurysm size, shape, and location and indicators of periaortic inflammation should be readily identifiable. Ultrasound is not as useful as CT or MRI in elucidating these findings. Several reports have also touted radionuclide-tagged white blood cell scans, but increased radio-tracer uptake needs to be matched with other imaging modalities to ensure that the hot area correlates with the aneurysm. Positron-emission tomography (PET)–CT scan theoretically should be the ideal imaging modality, but only a few cases have been reported.

The most specific findings of an infected AAA are those found at operation, namely, an aorta with a saccular or multilobed aneurysm surrounded by inflamed periaortic soft tissue, fluid, and pus spreading for a variable distance to involve adjacent structures. A positive culture of the aortic wall is definitive in the presence of these findings, although 20% to 25% of aortic cultures are negative. There is a reasonably high rate of positive cultures from the wall of routine, noninfected aneurysms (most commonly Staphylococcus epidermidis). The most commonly cultured organisms in recent reports are Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella species, but a large variety of gram-negative and fungal species have been reported.

A high index of suspicion is often required in order to establish the correct diagnosis in a timely manner. Once the diagnosis is confirmed, prompt surgical treatment is necessary because these aneurysms are prone to rapid enlargement and rupture. Rupture rates of 50% to 85% are typically reported, and a significant proportion of the ruptures are not discovered until the operation. There is no effective nonsurgical treatment for this condition, and hoping to cure the problem with only a long course of antibiotics, which can temporarily mask the clinical findings, is doomed to failure. However, in the absence of rupture, short-term antibiotic therapy may be useful to control sepsis in preparation for definitive surgical treatment.