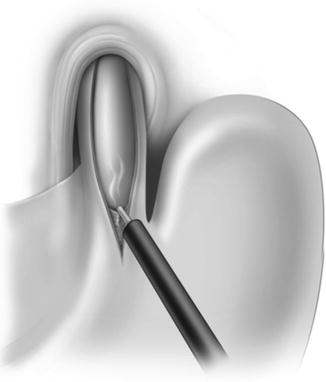

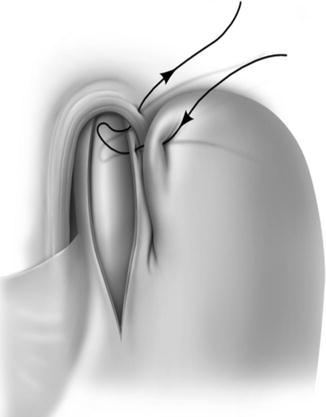

Fig. 12.1

Placement of the trocars

The instrumentation necessary for the laparoscopic myotomy is reported in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1

Instrumentation for laparoscopic Heller myotomy and partial fundoplication

Five 10-mm ports |

0° and 30° scope |

Graspers and needle holder |

Babcock clamp |

L-shaped hook cautery with suction-irrigation capacity |

Scissors |

Laparoscopic clip applier |

Electrothermal bipolar vessel sealing system |

Liver retractor |

Suturing device |

2–0 silk sutures |

Dissection

The gastrohepatic ligament is divided, beginning the dissection above the caudate lobe of the liver, where the ligament is thinner, and continuing toward the diaphragm until the right pillar of the crus is identified. The right pillar of the crus is separated from the esophagus by blunt dissection until the left crus is recognized, and the posterior vagus nerve is identified. Subsequently, the peritoneum and the phrenoesophageal membrane overlying the esophagus are divided, and the anterior vagus nerve is identified. The left pillar of the crus is then separated from the esophagus and dissected toward the junction with the right pillar of the crus. Blunt dissection is finally performed in the posterior mediastinum, laterally and anteriorly to the esophagus in order to have about 4–5 cm of esophagus without any tension below the diaphragm. No posterior dissection is necessary if an anterior fundoplication is planned. When dealing with a sigmoid esophagus, it is important to extend the dissection more proximally in the posterior mediastinum and to also dissect posterior to the esophagus. This dissection allows straightening of the esophageal axis, avoiding stasis of food after the myotomy.

Division of the Short Gastric Vessels

The short gastric vessels are taken down all the way to the left pillar of the crus, starting from a point midway along the greater curvature of the stomach [16].

Myotomy

The fat pad should be removed to expose the gastroesophageal junction, after identification of the anterior vagus nerve. Traction is then applied with a Babcock clamp, grasping below the gastroesophageal junction and pulling downward and to the left in order to expose the right side of the esophagus. A myotomy is performed on the right side of the esophagus in the 11 o’clock position using a hook cautery. The proper submucosal plane is found using the cautery, about 3 cm above the gastroesophageal junction.

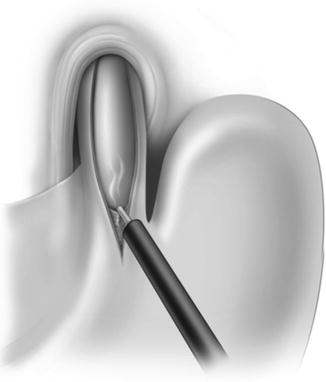

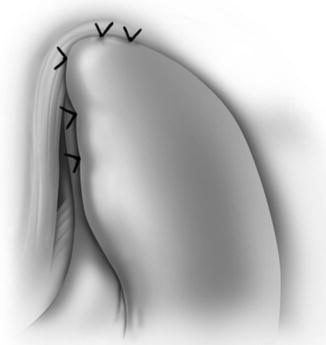

Once the mucosa is exposed, the myotomy is extended proximally for about 6 cm above the gastroesophageal junction and distally for 2.0–2.5 cm onto the gastric wall (Fig. 12.2) [19].

Fig. 12.2

Esophageal myotomy

It is important to be cautious in patients previously treated with prior intrasphincteric injection of botulinum toxin, as fibrosis can be present at the level of the gastroesophageal junction, with consequent loss of the normal anatomic planes. In these circumstances, the myotomy can be very difficult, and there is an increased risk of mucosal perforation [5, 20, 21]. If a perforation occurs, it is closed with fine (5–0) absorbable sutures.

The edges of the muscles are then separated with a dissector in order to have 30–40 % of the mucosa not covered by muscles.

Intraoperative endoscopy is rarely necessary, particularly when enough experience is present and a long myotomy onto the gastric wall is performed.

Because the main goal of the surgical treatment is the relief of dysphagia while preventing gastroesophageal reflux, several studies have addressed the role and type of fundoplication. A laparoscopic Heller myotomy alone is associated with postoperative gastroesophageal in about 50–60 % of patients, with the risk of developing esophagitis, Barrett’s esophagus, or a stricture [20, 22, 23]. If a total fundoplication is performed, there is an increased risk of persistent or recurrent dysphagia [13]. Therefore, a partial fundoplication added to the myotomy entails better functional results when compared to a total fundoplication because it takes into account the lack of peristalsis [13]. A recent multicenter, randomized controlled trial did not find significant differences in terms of control of gastroesophageal after the partial anterior in 49 patients and partial posterior fundoplication in 36 patients with achalasia [24]. A partial anterior fundoplication is often preferred because it is simpler to perform and covers the exposed esophageal mucosa [25].

Partial Anterior Fundoplication

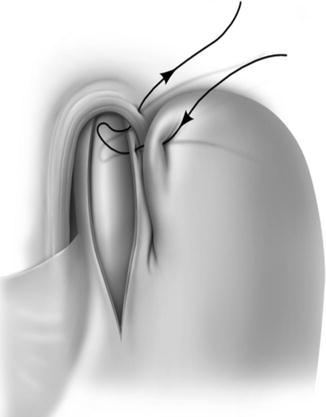

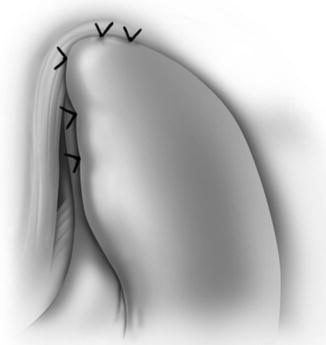

The partial anterior fundoplication is a 180° anterior fundoplication. Two rows of sutures (2–0 silk) are used. The first row is on the left side of the esophagus and has 3 stitches. The top stitch incorporates the fundus of the stomach, the muscular layer of the left side of the esophagus, and the left pillar of the crus (Fig. 12.3). The second and third stitches incorporate the gastric fundus and the muscular layer of the left side of the esophagus (Fig. 12.4). The fundus is then folded over the exposed mucosa so that the greater curvature of the stomach is next to the right pillar of the crus (Fig. 12.5). The second row of sutures on the right side of the esophagus consists of three stitches between the fundus and the right pillar of the crus. Finally, two additional stitches are placed between the fundus and the rim of the esophageal hiatus to eliminate any tension from the fundoplication (Fig. 12.6).

Fig. 12.3

Dor fundoplication: top stitch of the left row of sutures

Fig. 12.4

Dor fundoplication: second and third stitches of the left row of sutures

Fig. 12.5

Dor fundoplication: right row of sutures

Fig. 12.6

Completed Dor fundoplication

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree