Surgical Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation

Timothy S. Lancaster

Spencer J. Melby

Ralph J. Damiano Jr.

Introduction

The first effective surgical technique to treat atrial fibrillation (AF), now formally known as the Cox-Maze procedure, was introduced by Dr. James Cox in 1987 after extensive animal investigation. The procedure utilized a biatrial “cut-and-sew” technique in an attempt to guide the native sinus impulse to both atria and the atrioventricular (AV) node, while isolating ectopic atrial foci and blocking macroreentrant circuits that were felt to perpetuate AF. By simultaneously restoring sinus rhythm and maintaining atrial transport function, the Cox-Maze procedure effectively addressed the three detrimental sequelae of AF: (1) Palpitations, which cause patient discomfort and anxiety; (2) loss of synchronous AV contraction, which compromises cardiac hemodynamics; and (3) stasis of blood flow in the left atrium, which can result in thromboembolism and stroke. The first version of the Cox-Maze procedure was complicated by late chronotropic incompetence and a high rate of pacemaker implantation, prompting two further modifications to the surgical technique. The lesion set of the Cox-Maze III became the gold standard for the surgical treatment of AF, but despite its clinical success, the procedure was seldom performed due to its technical complexity and prolonged time on cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB).

The development of new ablation technologies and their incorporation into the current, fourth iteration of the Cox-Maze procedure have since revolutionized the surgical treatment of AF. Introduced clinically in 2002, the Cox-Maze IV consists of a combination of bipolar radiofrequency (RF) and cryothermal ablation lines that replace the majority of the surgical incisions of its predecessor. The modifications of the Cox-Maze IV have reduced the procedure’s technical complexity and time requirement and allow it to be performed through a less invasive right minithoracotomy approach, making the operation more accessible to cardiac surgeons and patients while achieving comparable results with less morbidity.

A variety of alternative surgical approaches to AF have also been described, including lone pulmonary vein isolation (PVI), extended left atrial (LA) lesion sets, ganglionic plexus ablation, and hybrid procedures. Overall results of these techniques have been inferior to the full biatrial lesion set of the Cox-Maze procedure, although a more limited

approach may be appropriate in certain patient populations and clinical scenarios. This chapter will focus on the technique of the Cox-Maze IV procedure performed via median sternotomy and right minithoracotomy.

approach may be appropriate in certain patient populations and clinical scenarios. This chapter will focus on the technique of the Cox-Maze IV procedure performed via median sternotomy and right minithoracotomy.

The indications for catheter and surgical ablation of AF are detailed in the 2012 Expert Consensus Statement of the Heart Rhythm Society Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Concomitant surgical ablation of AF at the time of another cardiac surgical procedure is indicated for (1) all symptomatic AF patients undergoing other cardiac surgical procedures, regardless of prior treatment with antiarrhythmic medications, and (2) selected asymptomatic AF patients undergoing cardiac surgery in which the ablation can be performed with minimal additional risk. Stand-alone surgical ablation should be considered for symptomatic AF patients who have failed medical management and either prefer a surgical approach, have failed one or more attempts at catheter ablation, or are not candidates for catheter ablation. Additional relative indications for surgery at our institution are (1) AF patients at high risk for stroke, such as patients with persistent AF and a CHADS2 score ≥2, who develop a contraindication to long-term anticoagulation, and (2) high-risk patients with persistent AF who have had previous cerebrovascular events while appropriately anticoagulated.

Relative contraindications to surgical AF ablation include a giant left atrium (≥8 cm in diameter), severe atrial fibrosis or calcification, and elderly patients (in general over 85 years of age). In asymptomatic patients undergoing concomitant surgery, an ablation procedure should be added only if it can be performed without increasing procedural morbidity and mortality. Relative contraindications to the right minithoracotomy approach include previous right thoracotomy, chest wall deformities, severely decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF ≤20%), and severe atherosclerotic disease of the aorta, iliac, or femoral vessels that precludes femoral cannulation for CPB.

Patient Evaluation

Most patients referred for surgical AF ablation have had appropriate evaluation of their arrhythmia prior to surgical evaluation. In patients lacking this workup or primarily referred for other pathology with coexisting AF, it is recommended that the surgeon obtain continuous Holter monitoring to characterize the severity of AF and inform the choice of procedure. Event monitors are particularly helpful in patients with paroxysmal arrhythmias to determine whether symptoms are related to arrhythmia occurrence.

Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) should be obtained in all patients to evaluate the nature and degree of concomitant valvular disease, to assess for the presence of atrial thrombus, and of particular importance, to determine LA size. Atrial substrate is an important predictor of operative outcomes, with a failure rate of over 50% observed in patients with LA diameter ≥8 cm. While TTE is used preoperatively to evaluate for the presence of LA clot, this assessment should be confirmed intraoperatively with transesophageal echocardiography (TEE). In patients who have failed catheter ablation, a chest CT scan with contrast is obtained to exclude pulmonary vein (PV) stenosis, which would require repair at the time of operation. Finally, coronary angiography is recommended in order to identify any existing lesions and to define the coronary anatomy. In patients with a left-dominant circulation, for example, the circumflex artery may be at risk of injury during the mitral isthmus ablation.

In patients evaluated for a right minithoracotomy approach, several additional considerations are of importance. A detailed history of pulmonary disease and sleep apnea should be obtained, with further evaluation undertaken if there are anticipated difficulties with performing single-lung ventilation. Historical factors including previous right

thoracotomy or risk factors for peripheral vascular disease (PVD) should be noted. Patients at risk of PVD and those over 65 years of age should undergo a CT angiogram of the thoracic and abdominal aorta, iliac, and femoral vessels and carotid Doppler ultrasound to assess the quality of aortic disease and the safety of femoral cannulation for CPB.

thoracotomy or risk factors for peripheral vascular disease (PVD) should be noted. Patients at risk of PVD and those over 65 years of age should undergo a CT angiogram of the thoracic and abdominal aorta, iliac, and femoral vessels and carotid Doppler ultrasound to assess the quality of aortic disease and the safety of femoral cannulation for CPB.

Antiarrhythmic and rate-control medications are generally continued through the morning of surgery. Patients who have been anticoagulated with warfarin are typically managed with intravenous heparin or bivalirudin in the preoperative period.

Selection of Procedure

While contemporary reviews of outcomes following surgical ablation continue to affirm the Cox-Maze procedure as the gold standard treatment for AF, alternative approaches may be appropriate in certain patient populations and clinical scenarios. The choice of surgical approach to AF ablation should be based on the presence of concomitant cardiac pathology, the nature of AF and other patient-specific characteristics, and a balancing of operative risk with optimal surgical outcomes. Three decades of basic science research and clinical experience have formed our method of clinical decision making, with the following reflecting our current practice pattern.

In patients evaluated for surgical AF ablation at the time of concomitant cardiac surgery, we recommend that a full biatrial Cox-Maze IV procedure be performed in those already undergoing CPB. In combination with mitral valve (MV) procedures in particular, a concomitant Cox-Maze IV procedure incurs minimal additional cross-clamp time and overall operative risk while achieving over 90% freedom from AF. The high success rate of the Cox-Maze procedure has also been documented for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), and we recommend a full Cox-Maze IV procedure in patients with AF at the time of on-pump CABG. In patients undergoing concomitant off-pump cardiac surgery, lone PVI may be an attractive alternative to the Cox-Maze lesion set because of the ability to perform the procedure without CPB. However, due to very low long-term success rates, we recommend lone PVI with removal of the left atrial appendage (LAA) only in patients who have existing comorbidity that would make CPB and/or additional procedures on the heart prohibitive.

Surgical ablation is performed through a median sternotomy when paired with concomitant procedures such as aortic valve replacement and coronary surgery. In patients evaluated for surgical ablation of lone AF without concomitant cardiac pathology, and in those with only concomitant mitral or tricuspid valve pathology, we perform the full Cox-Maze IV procedure via a right minithoracotomy in the absence of contraindications. In lone AF patients, median sternotomy is reserved for those with PVD that precludes femoral cannulation, a history of previous right thoracotomy, severe LV dysfunction, or chest wall deformities such as pectus excavatum.

Lone PVI can be considered in selected patients with lone paroxysmal AF and LA diameter ≤4 cm, and in this scenario PVI can be performed via a minimally invasive, bilateral thoracoscopic approach without CPB. Thoracoscopic PVI may also be considered in patients with lone AF and contraindications to femoral cannulation who wish to avoid median sternotomy, as results with lone PVI are superior to catheter-based ablation alone. However, we generally recommend the full Cox-Maze IV lesion set due to very poor long-term rates of freedom from AF with lone PVI.

Cox-Maze IV Procedure

Preparation

The patient is intubated using a regular endotracheal tube, and an introducer catheter is typically placed in the right internal jugular vein using ultrasound guidance. Generally, a pulmonary artery catheter (PAC) is not used since it often interferes with

performing the right atrial lesions. If it is felt to be necessary for postoperative monitoring, the PAC can be left in the superior vena cava (SVC) and advanced at the end of the case.

performing the right atrial lesions. If it is felt to be necessary for postoperative monitoring, the PAC can be left in the superior vena cava (SVC) and advanced at the end of the case.

Although all patients undergo a TTE during preoperative assessment, the LAA is not well visualized with this modality and thrombus cannot be excluded with certainty. The left atrium is therefore thoroughly examined with intraoperative TEE, and in those rare patients with identified thrombus, care is taken to minimize manipulation of the heart until exclusion of the LAA has been performed. The atrial septum is also assessed by TEE for the presence of a patent foramen ovale, which should be repaired if present. If the patient has concomitant MV dysfunction, this is assessed using two-dimensional, color-flow Doppler and three-dimensional modalities. At the conclusion of the procedure, TEE is used to confirm successful exclusion of the LAA and, when applicable, satisfactory repair or replacement of the MV.

Operative Technique—Median Sternotomy Approach

The Cox-Maze IV procedure can be broken down into three primary components: (1) PVI, (2) creation of the right atrial lesion set, and (3) creation of the LA lesion set. For the median sternotomy approach, the patient is positioned supine with both arms tucked at the sides, prepped with antiseptic solution, and draped with an iodophor-impregnated adhesive applied to the chest, abdomen, and groin. A median sternotomy is performed and the pericardium is opened in standard fashion. Bicaval and aortic cannulae are placed, and normothermic CPB is initiated.

Pulmonary Vein Isolation

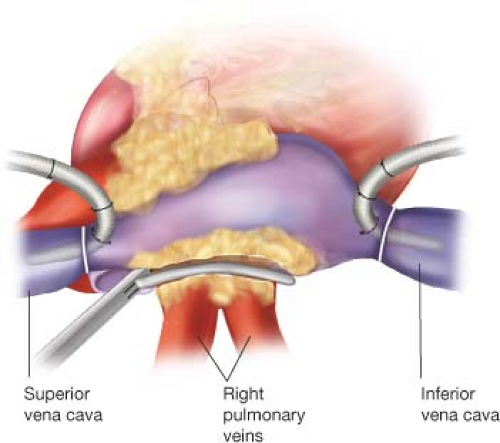

The right and left PVs are bluntly dissected, with care taken to fully dissect the epicardial fat pad off of the atrial surface, and are surrounded with umbilical tapes. If the patient is in AF at the time of surgery, amiodarone is administered and the patient is electrically cardioverted to normal sinus rhythm. Pacing thresholds are obtained from each PV using a bipolar pacing probe. The right and left PVs are each isolated using a bipolar RF clamp, such that a circumferential line of ablation surrounds as large a cuff of atrial tissue as possible (Fig. 40.1). For these and all subsequent lines created using the bipolar RF clamp, three discrete ablations are performed with slight adjustments in clamp position, effectively forming three closely approximated concentric circles to ensure isolation. If the surgeon is using a nonirrigated bipolar clamp, the jaws must be cleaned of char every 2 to 3 ablations in order to ensure the creation of transmural lesions. PV isolation is confirmed by documenting exit block, or failure of atrial capture, with epicardial pacing from each of the PVs. Further ablations are performed as needed until exit block is obtained.

Right Atrial Lesion Set

The patient is cooled to 34°C and the right atrial lesion set is performed on the beating heart. A small purse-string suture is placed at the base of the right atrial appendage (RAA) and a stab incision is made at its center, wide enough to accommodate one jaw of the bipolar RF ablation clamp. An ablation lesion is created with the clamp across the free wall of the RA down toward the SVC, taking care to avoid the sinoatrial (SA) node. A vertical atriotomy is then made from the interatrial septum up toward the AV groove near the free margin of the heart. This incision should be at least 2 cm from the first free wall ablation in order to avoid creating an area of slow conduction. A linear cryoprobe is used to create an endocardial cryoablation from the superior aspect of the atriotomy down to the tricuspid annulus at the 2 o’clock position. All cryoablations are performed for 3 minutes at −60°C. Cryoablation is preferable to RF ablation over annular tissues because it preserves the fibrous skeleton of the heart, avoiding any potential compromise of valve competency. The linear cryoprobe is then inserted through the previously placed purse-string suture and an endocardial cryoablation is created down to the tricuspid valve annulus at the 10 o’clock position. The bipolar RF clamp is then used to create ablation lines running from the inferior aspect of the right atriotomy up along the lateral aspect of the SVC and down the inferior vena cava (IVC). The SVC ablation should be performed as lateral and posterior as possible to minimize the risk of injury to the SA node, and the IVC ablation line should travel as far as possible onto the IVC (Fig. 40.2). Finally, the right atriotomy is closed in standard fashion, leaving the sutures untied for accommodation of a retrograde cardioplegia catheter that is left in the coronary sinus.

Left Atrial Lesion Set

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree