Chapter 71

Surgical Management of Vascular Malformations

Kristy L. Rialon, Steven J. Fishman

Based on a chapter in the seventh edition by Arin K. Greene and Steven J. Fishman

The proper diagnosis and treatment of vascular anomalies has long been impeded by misuse of terminology and nomenclature. Advances in our understanding of these disorders led to the creation of a biologic classification system, formally adopted by the International Society of the Study of Vascular Anomalies in 1996 (see Chapter 69).1,2 This classification scheme divides these anomalies into vascular tumors and vascular malformations on the basis of physical characteristics, natural history, and cellular features. Vascular tumors are true neoplasms that arise from cellular hyperplasia, whereas vascular malformations are congenital lesions originating from errors of embryonic development of blood vessels. Vascular tumors include infantile hemangioma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, and tufted angioma. Vascular malformations can be further subdivided according to vascular channel type (capillary, lymphatic, venous, arterial, or combinations thereof) or flow (slow versus fast). Slow-flow lesions include capillary malformations, lymphatic malformations (LMs), and venous malformations (VMs). Examples of fast-flow lesions include arteriovenous fistulae (AVFs) and arteriovenous malformations (AVMs).

Correct identification of the type of vascular anomaly is paramount to appropriate treatment selection. Lesions must be properly imaged before procedural planning. Ultrasonography, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging are the most common modalities used to determine the extent of the malformation. Angiography can also be useful for delineation of AVMs, demonstrating the nidus and its feeding vessels, along with flow characteristics.3,4 For complex LMs, lymphangiography may occasionally be useful to delineate the aberrant anatomy of the lymphatics.

In general, when treated, vascular malformations are addressed with sclerotherapy, embolization, or surgical excision. Percutaneous needle and catheter-based techniques are discussed in Chapter 72. Preoperative embolization or sclerotherapy may decrease intraoperative blood loss and increase the likelihood of clinical success.5–9 Complete surgical resection may not be achievable, and lesions may require multiple or staged procedures. Here we describe surgical treatment options for vascular malformations.

Low-Flow Malformations

Capillary Malformations

Capillary malformations are present at birth and typically appear as flat, pink-red cutaneous lesions. They can be associated with underlying soft tissue and skeletal overgrowth as well as other internal abnormalities. Resection is not usually necessary for isolated capillary malformations, and treatment consists primarily of flash lamp pulse-dye laser therapy for cosmetic purposes. They may, however, be partially resected during debulking procedures for underlying venous or lymphatic malformations.

Lymphatic Malformations

Lymphatic malformations are often classified as macrocystic (diameter >1 cm), microcystic (diameter <1 cm), or a combination of the two. This description of the type of LM, along with its location and extent, is useful in the determination of treatment options.10 Presentation can vary from a localized mass to a diffuse anomaly. LMs are unique among vascular anomalies in that they not only can serve as a source of infection, causing cellulitis or bacteremia, but also are affected by illness occurring elsewhere in the body, increasing in size in response to infection. Cervicofacial LM is common in the head and neck region and can manifest as breathing and swallowing difficulties. Congenital anomalies of the central lymphatics can manifest as chylothorax or chylous ascites, respiratory compromise, malnutrition and hypoproteinemia, lymphopenia, and bony erosion.11 Intralesional bleeding may also occur secondary to trauma or an abnormal venous connection. Cutaneous involvement of LMs manifests as reddish-purple to black vesicles, which can leak serosanguineous fluid.

In general, LMs that are predominantly macrocystic are amenable to sclerotherapy (see Chapter 72), whereas those that are microcystic in nature often require resection. Extremely large macrocystic lesions may be best resected, because sclerotherapy may require many sessions and still leave a significant residual mass. Lesions with poor response to sclerotherapy can be resected. Asymptomatic lesions can be observed. Indications for treatment include deformity, dysfunction, leakage into body cavities or from the skin, and recurrent infections. Because these operations may be lengthy, surgery should generally be delayed until the patient is 6 months of age, unless the airway is threatened.

Operative Treatment

LMs can cause considerable tissue expansion, and thus, for larger lesions, a lenticular excision should be made. Skin altered by creases, dimpling, or vesicles may often be included in the excision to minimize eruption of lymphatic cutaneous vesicles later. The LM is then dissected off the underlying skin and subcutaneous tissue. The appearance of microcystic LM is similar to that of fat but has a distinguishable texture. In situations in which there is no normal subcutaneous tissue and the LM extends into the dermis, a deep subdermal dissection plane can be created to ensure sufficient vascularity for the flap. An intraoperative nerve stimulator is helpful, particularly when the LM encompasses neurovascular structures. Because LMs are not malignant lesions, the entirety of a lesion need not be removed, and care should be taken to preserve any vital structures. Subsequent procedures may be necessary to remove residual LM or to recontour areas left by the initial resection (Fig. 71-1). Reoperations can be much more difficult, so every effort should be made to be as thorough as possible at the initial operation. Depending on how much LM is left behind, any residual lesion may reexpand in the months following surgery. Closed-suction drains are placed in the wound to absorb lymphatic leakage. Excision of redundant skin may be required to close the skin in a cosmetic fashion. Complex flaps may be needed for adequate tissue coverage and cosmetic reconstruction.12

Figure 71-1 A, Lymphatic malformation of left neck, axilla, mediastinum, and upper extremity in a baby girl, shown shortly after birth. B, Same girl, age 3 years, after multiple sclerotherapy and debulking procedures. C, Same girl, now age 10 years, who is active in dance and other activities.

Treatment of symptomatic abdominal and pelvic LMs may require removal of associated viscera. LMs of the gastrointestinal tract can cause pain and obstruction, and bowel resection may be required for symptomatic relief. Patients in whom splenomegaly or hypersplenism develops may benefit from splenectomy.

Management of leakage from lymphatic anomalies can be difficult. Chylous pleural effusions from thoracic LMs can sometimes be treated with chemical or mechanical pleurodesis. LMs of the pericardium causing pericardial fluid accumulation can be treated with a pericardial window or repeated pericardiocentesis by needle or indwelling catheter. Nonoperative management aimed at decreasing the total volume of lymph fluid, such as with octreotide, low-fat diets, or total parenteral nutrition, may reduce thoracic duct flow. Ligation of the thoracic duct can be useful but should be performed with caution in patients with diffuse lymphatic anomalies, because outflow obstruction may exacerbate symptoms. In some rare cases, shunt procedures can provide palliation.

LM can occur in the subcutaneous tissue of the penis. Lymphedematous swelling of the penis not controlled by wrapping can be excised. The entire thickness of the subcutaneous tissue should be removed to minimize recurrent swelling. Clitoromegaly caused by an LM can be treated with corporal resection, but care should be taken to preserve the neurovascular bundles.

Postoperative Management

Closed-suction drains are left until output is minimal. They may remain for weeks to months, so patients should be warned preoperatively regarding the duration of drainage.

Cutaneous vesicles, from unexcised lymphatic channels, may occur within or near the surgical scar following resection but can be controlled by local intravesicular sclerotherapy or CO2 laser treatment. They can be resected, but owing to their extensive nature, recurrence is common. To prevent development of vesicles, involved skin should be excised and uninvolved dermis advanced over the resection bed to the extent possible during the procedure.

Venous Malformations

Venous malformations may be present at birth and typically grow with the patient, although symptoms may not arise for some time. They expand with dependent position and Valsalva maneuver. Stasis in VMs can lead to phlebothrombosis, causing pain and swelling. VMs of the bone and joints can lead to fractures and hemarthroses. VMs involving the muscle can also manifest as pain and swelling, which are exacerbated by dependent position and exertion, and can cause associated skeletal problems, including fracture, overgrowth, deformation, and undergrowth.13

Asymptomatic VMs can be managed initially with compressive garments and daily aspirin to minimize thrombotic episodes. Injection sclerotherapy is often very effective in treating VM (see Chapter 72). Surgery is reserved for symptomatic lesions, cosmesis, or functional impairment. Those that are well-localized are most amenable to surgical excision (Fig. 71-2). Large lesions can be debulked if they are causing uncontrolled pain, significant limb length discrepancy, bleeding, severe cosmetic problems, impairment in function, or limitation of range of motion. Ideally, each patient should be assessed by a multidisciplinary team with the capacity to offer all therapeutic options. Some lesions are best treated with a combination of injection sclerotherapy and resection. Preoperative sclerotherapy can also be used to decrease operative blood loss.

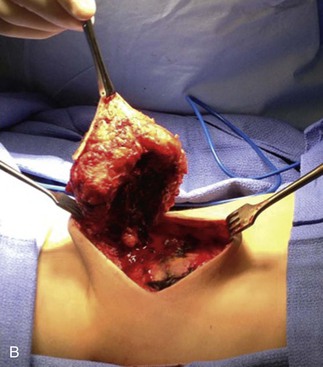

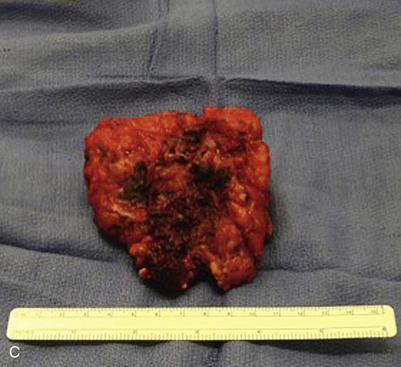

Figure 71-2 A, Two-year old boy with a large venous malformation of the lower back. B, Resection of the venous malformation demonstrating the creation of flaps. C, The venous malformation following resection. D, Same boy at 2-month follow-up.

VMs of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract can occur anywhere from mouth to anus.

Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a rare disorder characterized by multifocal venous malformations, most commonly involving the skin and GI tract.14 These lesions in the bowel can cause intussusception, manifested as intermittent abdominal discomfort and, occasionally, intestinal obstruction. Some lesions may never cause symptoms and require no intervention. Minor or occult fecal blood loss can often be managed conservatively with iron supplementation. Severity and frequency of bleeding can be reduced with stool softeners and avoidance of constipation. Exsanguinating hemorrhage is rare. However, the patient with an acute small bowel obstruction warrants an operation. Chronic anemia, particularly if transfusions are required, can usually be solved with individual resection of each lesion in the GI tract, sometimes a very tedious undertaking.15

Operative Treatment

VMs have fragile, dysmorphic vessels and infiltrative presence into surrounding tissues, which can result in significant blood loss with dissection. Cutting through a VM leaves a surface resembling a sponge, and bleeding is difficult to control with cautery, clamps, or sutures. For an extremity VM, the use of a tourniquet can decrease intraoperative blood loss. Hemostatic devices such as bipolar sealers, electrocautery, and ultrasonic scalpels can be useful. Involved skin should be incorporated in the incision to the extent that primary closure can be achieved and subsequent scar location and configuration is acceptable. A VM can often act as a tissue expander, allowing a large amount of involved skin to be removed with the specimen (see Fig. 71-2). Flaps are raised outward from the incision. When the lesion involves or is just below the dermis, flaps should be made as thin as possible without devascularizing the skin. Care should be taken to preserve major vessels, nerves, muscles, tendons, and joint cavities. Closed-suction drains are placed under the flaps. Rarely, large resection areas can be covered by local or distant flaps or with the use of grafts.

Diffuse colorectal VMs, involving large continuous segments of bowel, are often seen in Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and require more than simple excision; they can be managed with colectomy, anorectal mucosectomy, and coloanal pull-through.16

An anorectal VM can be associated with an ectatic inferior mesenteric vein, which can siphon blood flow from the portal vein.17 The siphoning causes stagnation of blood, resulting in portomesenteric thrombosis and resultant portal hypertension. Patients with rectal VMs should be screened for this anomaly, which if found can be ligated proximally to prevent portal sequelae.

Although a bulky VM of the scrotum may be amenable to sclerotherapy, repeated sessions should be avoided to minimize radiation exposure, and thus, surgical resection is preferable. Sclerotherapy of labial VMs can be performed, as long as female gonads are shielded. Debulking is often best undertaken after puberty unless overgrowth is dramatic. Sclerotherapy of the clitoris should generally be avoided.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree