Chapter 25 Surgical Management of Atherosclerotic Renal Artery Disease

The introduction of new, more potent antihypertensive agents and percutaneous endovascular techniques has influenced surgical intervention for atherosclerotic renal artery disease (ARAS).1 Many physicians currently limit surgical intervention to severe hypertension despite maximal medical therapy, or disease patterns not amenable to percutaneous transluminal renal artery angioplasty (PTRA), or renovascular disease associated with excretory renal insufficiency (i.e., ischemic nephropathy). As a result, the patient population selected for operative management is often characterized by bilateral ostial renal artery stenosis (RAS) or occlusion (85%) superimposed on diffuse extrarenal atherosclerotic disease (91%) in combination with renal insufficiency (60%).1–3

Prevalence, Evaluation, and Diagnosis

Prevalence

As discussed in Chapter 23, it has long been recognized that anatomical renal artery disease may be clinically silent. Conversely, the disease may account for 3% of hypertension within the general population. Of patients presenting for chronic renal replacement therapy, 10% to 20% have renal artery disease.4–6 Although its prevalence in patients with mild hypertension is low, renovascular disease is frequently present in patients with severe hypertension. Dietch et al. found that 50% of patients aged 60 years or older with diastolic blood pressure 104 mmHg or higher demonstrated significant RAS or occlusion.5 When these characteristics were associated with serum creatinine (SCr) greater than 2.0 mg/dL, the prevalence of renal artery disease increased to 70%. Half of these latter patients demonstrated bilateral renal artery disease.

Evaluation

Through continued improvements in software and probe design, renal duplex ultrasonography is an accurate and reliable method to identify hemodynamically significant renal atherosclerotic disease.7,8 The examination poses no risk to residual excretory renal function, and overall accuracy is not affected by concomitant aortoiliac disease. In addition, preparation is minimal (an overnight fast), and there is no need to alter antihypertensive medications.

When evaluating for renovascular renal insufficiency, a negative renal duplex ultrasound examination effectively excludes ischemic nephropathy because the primary consideration is global renal ischemia based on main renal artery disease affecting both kidneys. When screening for renovascular hypertension, however, a negative duplex ultrasound examination does not reliably exclude surgical disease due to stenotic accessory arteries or branch renal artery disease.7 Despite enhanced recognition of multiple arteries by color Doppler flow, only 40% of these accessory renal vessels are currently identified by renal duplex ultrasound examination.

Aortography and renal angiography may be indicated after a positive duplex ultrasound study in selected patients. Patients with severe hypertension and negative or nondiagnostic duplex ultrasound examinations, especially children and young adults, should also undergo angiography. Diagnostic digital subtraction angiography (DSA) can be performed with minimal risk in an outpatient setting. In planning open operative therapy, imaging includes lateral aortography to evaluate the mesenteric vessels. Concurrent mesenteric artery disease was identified in 50% of patients with significant RAS in an angiographic case series of U.S. veterans.9 In an elderly population-based cohort, the authors identified a significant and independent association of mesenteric artery stenosis with renal artery stenosis.10 Concurrent mesenteric artery disease has bearing on the use of splanchnorenal reconstruction.

Diagnosis

When a unilateral renal artery lesion is confirmed in an adult patient with severe hypertension, its functional significance should be defined. Unfortunately, measurement of renal vein renin does not have great value when severe bilateral disease or disease to a solitary kidney is present. Therefore, the decision for empirical intervention is based on severity of the renal artery lesions, severity of hypertension, and degree of associated renal insufficiency. In the latter instance, issues determining recovery of excretory renal function in patients with ischemic nephropathy remain ill-defined. Our center’s experience with over 240 patients with severe hypertension (mean, 201/104 mmHg) and a preoperative SCr of 1.8 mg/dL or greater has demonstrated a significant association between improved renal function after operative intervention and the site of renal artery disease, extent of renovascular repair, and rate of decline in preoperative renal function.1,2,11–15Complete renal artery repair after a rapid decline in excretory renal function is associated with the best opportunity for recovery of renal function.11,12,14 Most importantly, improved renal function after operation is the primary determinant of dialysis-free survival among patients with preoperative ischemic nephropathy.14

Surgical repair of unilateral renal artery disease may be appropriate as a combined aortic procedure in the absence of functional studies (e.g., renal vein renin assay) when hypertension is severe, the patient does not have significant risk factors for operation, and the probability of technical success is certain (>99%). In these circumstances, correction of a renal artery lesion may be justified to eliminate all possible causes of hypertension and renal dysfunction. Because the probability of blood pressure benefit is lower in such a patient, morbidity from the procedure must also be predictably low.3,16

When a patient has bilateral RAS and hypertension, the surgical decision to intervene is based on severity of the renovascular lesions and degree of hypertension.2,16 If the pattern of renal artery disease consists of severe stenosis on one side and only mild or moderate disease on the contralateral side, the patient is treated as though only a unilateral lesion exists. If both renal arteries have only moderately severe disease (65%-80% diameter-reducing stenosis), renal revascularization is undertaken only if hypertension is severe. In contrast, if both renal artery lesions are severe (>80% stenosis) and the patient has resistant hypertension despite medical therapy, bilateral simultaneous renal revascularization is performed.

Furthermore, at least mild excretory renal insufficiency is often present. Because renal insufficiency usually parallels the severity of hypertension, a patient who presents with severe renal insufficiency but only mild to moderate hypertension usually has renal parenchymal disease. Characteristically, renovascular hypertension associated with severe renal insufficiency or dialysis dependence is associated with very severe bilateral stenoses or total renal artery occlusions.2,14 When considering repair of renal artery disease, one should evaluate the clinical status with respect to this characteristic presentation.

Management Options

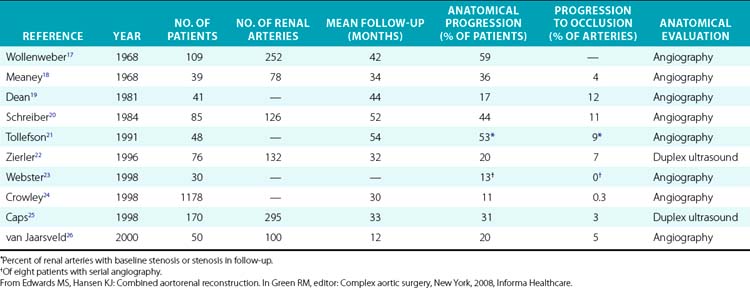

Management of renal artery disease discovered incidentally during evaluation of cardiac, aortoiliac, or infrainguinal disease is controversial. In this setting, the decision must address the need for additional diagnostic tests and the decision whether or not to perform combined intervention. Advocates for combined intervention frequently cite “natural history” data (Table 25-1) that suggest atherosclerotic lesions of the renal artery frequently progress and progression is associated with irretrievable decline in kidney size and function. Recent experience, however, disputes this view. In an 8-year follow-up study of Cardiovascular Health Study participants,27 no individual with hemodynamically significant RAS at baseline demonstrated progression on follow-up. Renal artery stenosis at baseline was not associated with a decline in kidney size or function. In the absence of renovascular hypertension or insufficiency (i.e., ischemic nephropathy), these prospective data suggest that incidental renovascular disease should not be submitted to intervention by any method. This conclusion is supported by the retrospective experience reported by Williamson et al.28

No prospective randomized clinical trial compares medical management, percutaneous renal angioplasty with stent, and surgical reconstruction in patients with atherosclerotic renovascular disease (also see Chapter 24). In patients with functionally significant renal artery lesions and severe hypertension, contemporary results of operative management argue for a selective approach toward renal artery intervention.1,2 Whether by open surgical repair or catheter-based methods, indications for intervention are the same. These include all patients with severe or difficult-to-control hypertension, especially when associated with renal insufficiency. Patient age, type of lesion, medical comorbidity, and concomitant aortic disease must be considered in selecting patients for open surgical or endovascular management. In the complete absence of hypertension, renal artery intervention is not recommended by any method.

Operative Management

General issues

The presence of severe hypertension is considered a prerequisite for renal artery intervention. In general, functional studies are used to guide management of unilateral lesions. Empirical renal artery repair is performed without functional studies when hypertension is severe and renal artery disease is bilateral or the patient has ischemic nephropathy.1,12,14 Accordingly, prophylactic renal artery repair in the absence of hypertension, whether as an isolated operative or catheter-based procedure or combined with aortic reconstruction, is not recommended. With the exception of disease requiring bilateral ex vivo reconstructions that are staged, all hemodynamically significant renal artery disease is corrected in a single operation. Having observed beneficial blood pressure and renal function response regardless of kidney size or histological pattern on renal biopsy, nephrectomy is reserved for unreconstructible renal artery disease to a nonfunctioning kidney (i.e., <10% function by renography).3,7,12,14 Direct aortorenal reconstructions are preferred over indirect methods because concomitant disease of the celiac axis is present in 40% to 50% of patients, and bilateral renal artery repair is required in 50%.3,9 Failed surgical repair is associated with a significant and independent increased risk of eventual dialysis dependence.3 To minimize these failures, intraoperative duplex ultrasound is used to evaluate the technical results of surgical repair.29

Operative techniques

Aortorenal Bypass

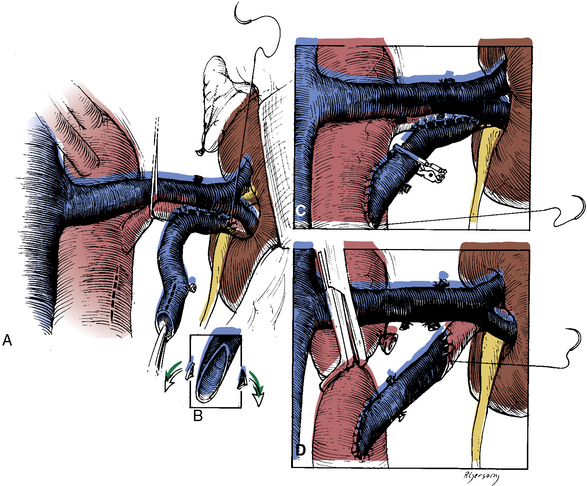

The most common method of revascularization is aortorenal bypass (Fig. 25-1). Three types of material are available for conduit: autologous saphenous vein, autologous hypogastric artery, and prosthetic grafts. The choice of conduit depends on a number of factors. In adults, we preferentially use the saphenous vein. However, if the vein is small (<4 mm in diameter) or sclerotic, the hypogastric artery or a synthetic prosthetic graft may be preferable. A 6-mm, thin-walled polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft is satisfactory when the distal renal artery is of large caliber (≥4 mm) and provides long-term patency equivalent to that of saphenous vein.

Figure 25-1 Technique for end-to-side (A-C) and end-to-end (D) aortorenal bypass grafting.

(From Benjamin ME, Dean RH: Techniques in renal artery reconstruction: part I. Ann Vasc Surg 10:306–314, 1996.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree