Surgical Approaches for Heart Failure

Nicholas G. Smedira

Katherine J. Hoercher

Randall C. Starling

Heart failure surgery has been called “high-risk” conventional or nontransplant surgery. These procedures represent the evolution of well-known operations such as coronary bypass grafting, valve interventions, and left ventricular (LV) reconstruction now applied to patients with severe LV dysfunction. Perceived as incurring a substantial early risk, many patients in the past were not offered a surgical alternative other than transplantation. An increasing body of evidence has demonstrated that surgical procedures and devices to arrest or reverse remodeling are safely performed in the failing heart, improve LV function, and may play a key role in providing lasting benefit for patients with heart failure. Surgery for advanced heart failure has become a common treatment of choice for many patients. A key ingredient to the success of any surgery for heart failure is the combination of state-of-the-art pharmacologic therapy. When used together, medical and surgical therapies offer marked improvement in both quantity and quality of life for the many patients suffering from end-stage heart failure.

At the time the first edition was being written, we were assessing the use of conventional surgical therapies and beginning to explore multiple new surgical options to address the problem of heart failure with the belief that symptoms would be reduced and survival improved with an acceptably low operative mortality. Many studies have confirmed the low operative risks and two eagerly awaited randomized trials—Randomized Evaluation of Mechanical Assistance for the Treatment of Congestive Heart Failure (REMATCH) and Acorn CorCap—provide insight into the utility of surgical therapy for advanced heart failure. This chapter reviews the current status of surgical treatments for heart failure, focusing on results that have been published since the last edition and highlighting changes in our understanding of how surgery impacts survival and quality of life.

Risk Assessment

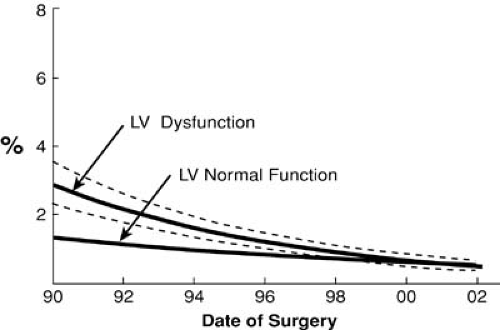

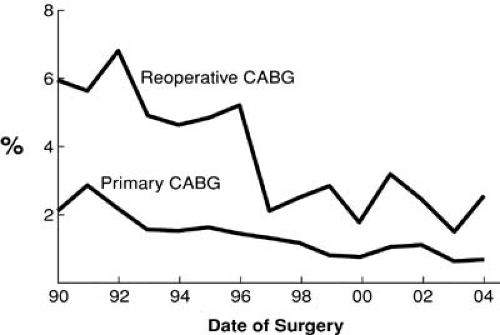

The risk of all cardiac surgery has declined over the past decade. Perioperative risks have diminished owing to improvements in intraoperative myocardial protection, increased surgeon experience, and more consistent postoperative care strategies. For example, hospital death after reoperative coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) is now less than 2%. This is clinically indistinguishable from the 1% mortality of patients undergoing primary CABG (Fig. 91.1). This must be interpreted with caution, however; we have found that older age, smoking, renal dysfunction, and poor LV dysfunction decreased the likelihood of undergoing reoperation (1). All these factors have been shown to increase the morbidity and mortality associated with reoperation and may have biased the decision against surgery in favor of medical therapy or percutaneous intervention (1).

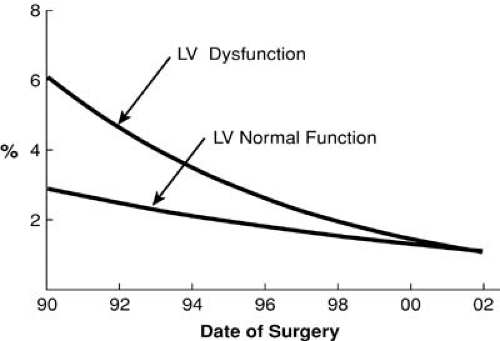

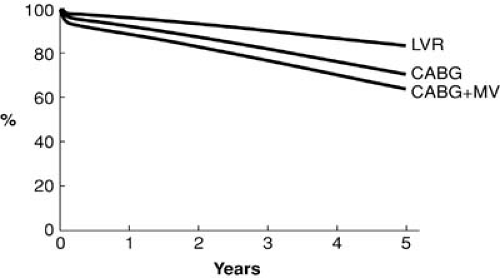

Many small series have described operative mortalities of less than 2% in patients with severe heart failure and reduced LV function. The Cleveland Clinic experience from the early 1990s demonstrated reduced ejection fraction (EF) was associated with a marked increase in mortality in patients undergoing primary or reoperative CABG. This risk factor was eliminated by 2002 (Figs. 91.2 and 91.3) (1). This statistic is further underscored by a recent study of contemporary outcomes of nontransplant surgical strategies for managing ischemic cardiomyopathy. From January 1997 to July 2003, 1,108 patients at the Cleveland Clinic with ischemic cardiomyopathy and an EF of less than 35% underwent CABG alone (n = 760), CABG plus mitral valve (MV) repair (n = 191), or LV reconstruction (n = 167). All three strategies demonstrated a hospital mortality of less than 5% and an excellent 5-year survival (Fig. 91.4). Rather than a low EF, we found the presence of comorbidities, especially renal dysfunction, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and vascular disease, to be more powerful predictors of early death. Other studies have repeatedly shown that parameters of LV function reflecting a reduced EF have little impact on early surgical mortality. Although there remains an incremental risk during bypass surgery produced by abnormal LV function, with modern myocardial protection that increment is small and represents a relatively small proportion of the total risk for patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy. A review of 14,075 Cleveland Clinic patients undergoing primary

isolated bypass surgery from 1990 to 1999 showed in-hospital mortality rates when preoperative LV function was normal (n = 7,203) of 1.5%, mild impairment (n = 3,378) of 0.8%, moderate impairment (n = 2,132) of 2.5%, and severe impairment (n = 1,362) of 3.2%.

isolated bypass surgery from 1990 to 1999 showed in-hospital mortality rates when preoperative LV function was normal (n = 7,203) of 1.5%, mild impairment (n = 3,378) of 0.8%, moderate impairment (n = 2,132) of 2.5%, and severe impairment (n = 1,362) of 3.2%.

FIGURE 91.1. Operative mortality for all primary and reoperative CABG at The Cleveland Clinic Foundation. |

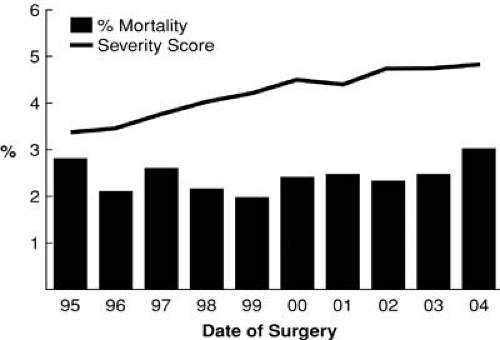

The Cleveland Clinic Risk Score was developed in 1988 and is still in use today. It determines preoperative risk factors for patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery (2). Compared with the 1980s, patients undergoing surgery in this decade are at much higher estimated risk as a result of an older population, higher number of reoperations, emergency operations, the incidence of LV dysfunction, and the presence of comorbidities, such as diabetes and renal dysfunction. Yet despite this, these patients have a significantly lower incidence of morbidity and hospital mortality (Fig. 91.5) (2,3).

We now have solid data to demonstrate that surgical risk has been substantially reduced for even the patients at highest risk, but therein lies the quandary. Given that the vast majority of patients will survive the operation, the much more difficult question is this: Do these procedures improve symptoms and prolong survival? The remainder of this chapter addresses these concerns.

TABLE 91.1 CABG with Severe LV Dysfunction | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|