Surgical Anatomy of the Lungs

Thomas W. Shields

Until the mid-twentieth century, the anatomy of the lungs was a little understood and seemingly unimportant subject. With the development of radiographic and endoscopic techniques and the advancement of pulmonary surgery, detailed anatomic knowledge of the lungs became a necessity.

The essential anatomic unit of the lung, the bronchopulmonary segment, was established as that portion of the lung substance that represents the total branching of a major, segmental subdivision of a lobar bronchus. These units are named for their topographic position in the lung.

Lobes and Fissures

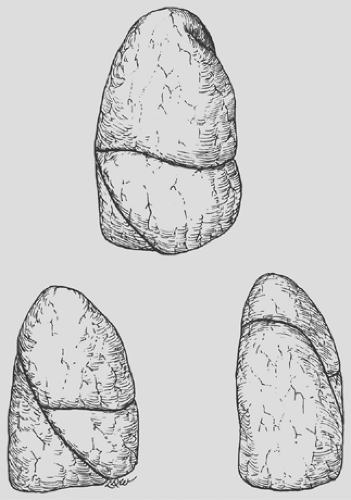

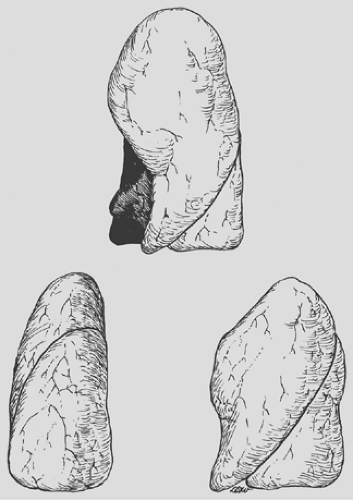

The right lung is composed of three lobes (the upper, middle, and lower) and is the larger of the two lungs. The left is made up of only two lobes, the upper and lower. Two fissures are usually present on the right. The oblique (major) fissure separates the lower lobe from the upper and middle lobes, and the horizontal (minor) fissure separates the other two (Fig. 5-1). In life, the oblique fissure on the right begins posteriorly at the level of the fifth rib or intercostal space, runs downward and forward approximating the course of the sixth rib, and ends at the diaphragm in the vicinity of the sixth costochondral junction. The horizontal fissure begins in the oblique fissure in the region of the midaxillary line at the level of the sixth rib and runs anteriorly to the costochondral junction of the fourth rib. The oblique (major) fissure is found on the left (Fig. 5-2). This begins at a somewhat higher level posteriorly, between the third and fifth ribs and runs downward and forward to end in the region of the sixth or seventh costochondral junction.

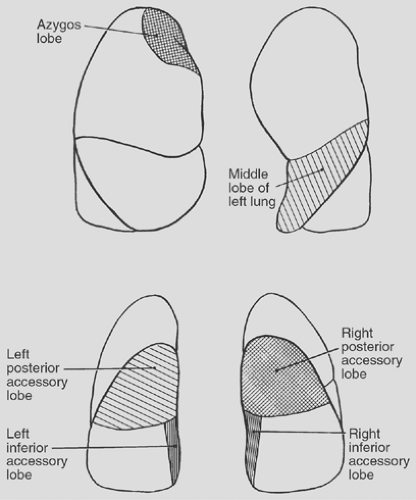

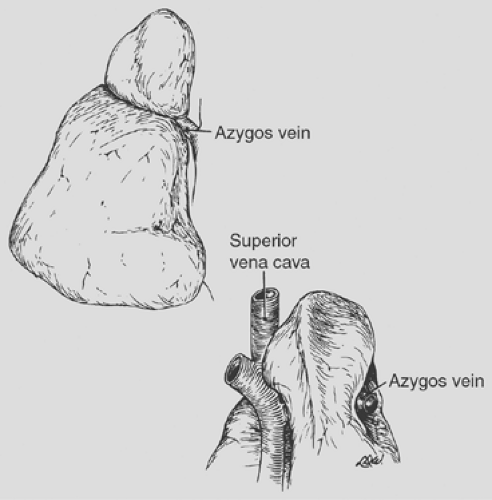

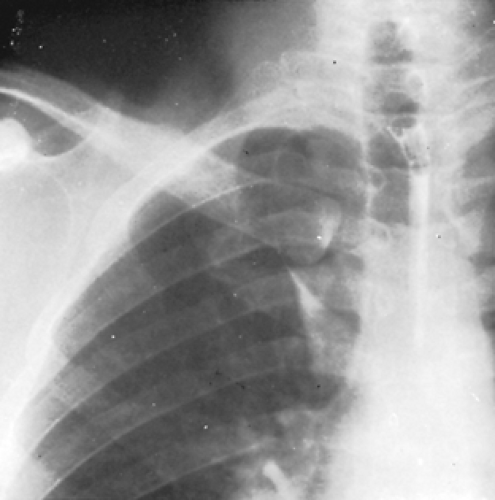

Variations in the fissures do occur, and often part or all of a fissure fails to develop. This is seen commonly as a more or less complete fusion of the middle lobe and the anterior portion of the upper lobe in more than 50% of lungs examined. Accessory fissures occur also, and certain portions of the lung may be demarcated into so-called accessory lobes. On occasion, such fissures are visible as linear shadows on the radiograph of the chest, and the accessory lobe may appear less radiolucent than the surrounding portions of the lung. The usual accessory lobes are the posterior accessory, inferior accessory, middle lobe of the left lung, and azygos lobe (Fig. 5-3). In contrast to the first three named, which are true accessory lobes made up of specific bronchopulmonary segments, the azygos lobe is not a true accessory lobe because it is formed of varying portions of one or two segments (apical and posterior) of the right upper lobe. The fissure is formed by an aberrant loop of the azygos vein and its mesentery of two layers of the parietal pleura and two of the visceral pleura (Fig. 5-4). On the radiograph, this fissure may appear as an inverted comma to the right of the mediastinum (Fig. 5-5). This anomaly is seen in 0.5% to 1.0% of the anatomic dissections and routine radiographs of the chest.

Bronchopulmonary Segments

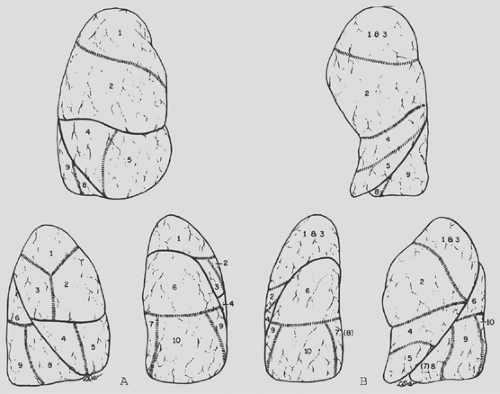

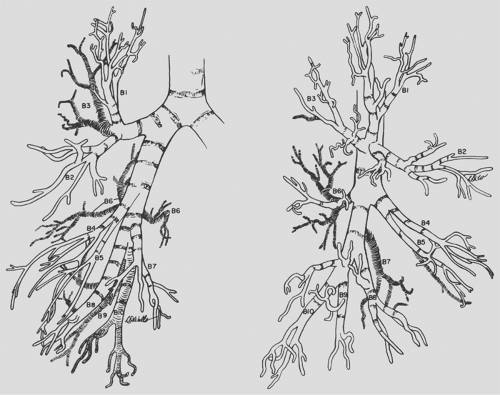

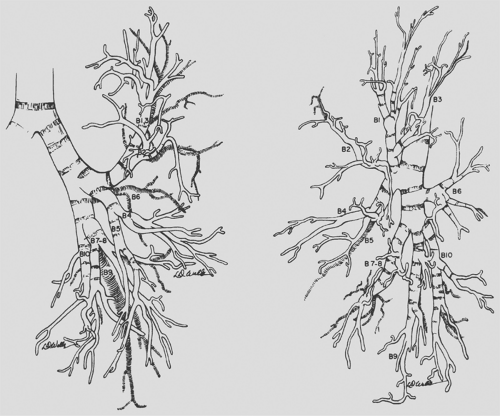

Each lobe of the right and left lungs is subdivided into several individual anatomic units, the bronchopulmonary segments. The general pattern is that of 18 segments, 10 in the right lung and 8 in the left. Initially, there were many differences in the nomenclature for the various segments as the result of the publications of the individual investigators working in North America and in Europe. Sealy and associates68 presented an excellent review of this topic in 1993. The terminology suggested by Brock15 in 1946 and Jackson and Huber34 in 1943 and that adopted by the Ad Hoc International Committee on Nomenclature, which was published for the latter by Brock16 in 1950, are shown in Table 5-1. Subsequently, in 1989, the latest Nomina Anatomica nomenclature for the lung segments was published; it is essentially that suggested originally by Jackson and Huber34 (Table 5-2). However, the numerical designations, especially those for the segments and structures of the right and left upper lobes, are dissimilar. Most surgeons in America use the numbers suggested by Jackson and Huber34 and Boyden13,14 (see Table 5-2). However, Overholt and Langer61 and Beattie and colleagues5 have used the numerical designations adopted by the Nomina Anatomica.58 Likewise, as noted by Wakabayashi (personal communication, 1996), the Japanese surgeons use the Nomina Anatomica numerical designations as well. Therefore one should be aware of the discrepancies in the literature relative to the numerical designations for the various segments and the structure contained therein (bronchi, veins, and arteries). In this text, the terms and numbers used throughout are those suggested by Jackson and Huber34 and Boyden.13,14 The topographic positions of the segments are shown in Figure 5-6. Knowledge of the detailed anatomic features of the bronchial distribution and the vascular supply of each segment is essential for the surgeon. Although a general pattern exists in the anatomic features in each segment, variation is the rule. The usual pattern and the most common deviations from it are best portrayed by separate descriptions

of the bronchial, arterial, and venous systems. The described anatomic patterns and variations of the bronchi and pulmonary arteries and veins have been selected by the author primarily from the studies of Birnbaum11; Bloomer, Liebow, and Hales12; and Boyden.14

of the bronchial, arterial, and venous systems. The described anatomic patterns and variations of the bronchi and pulmonary arteries and veins have been selected by the author primarily from the studies of Birnbaum11; Bloomer, Liebow, and Hales12; and Boyden.14

Figure 5-1. Anterior, lateral, and posterior aspects of the right lung. (Redrawn and modified from Anson BJ, ed. Atlas of Human Anatomy. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1950:199.) |

Figure 5-2. Anterior, lateral, and posterior aspects of the left lung. (Redrawn and modified from Anson BJ, ed. Atlas of Human Anatomy. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1950:199.) |

Bronchial Tree

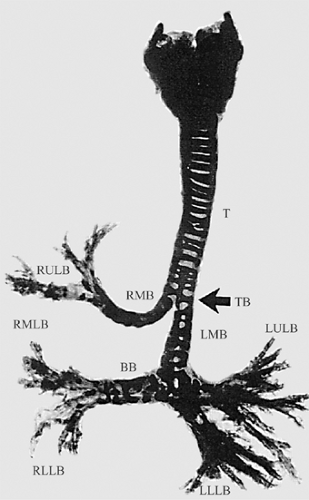

The trachea bifurcates at about the level of the seventh thoracic vertebra into the right and left mainstem bronchi. Compared with the left bronchus, which arises at a sharper angle, the right bronchus arises in a more direct line with the trachea, an important factor in the localization of aspirated material.

Right Bronchial Tree

The length of the right main bronchus from the trachea to the point where the right-upper-lobe bronchus branches from its lateral wall is about 1.2 cm. The upper-lobe bronchus, about 1 cm in length, in turn gives off three segmental bronchi—one to the apical, one to the posterior, and one to the anterior segment. The branching may be a simple trifurcation or include

varying combinations of the three major branches. The segmental bronchi further subdivide to supply the various portions of the segments.

varying combinations of the three major branches. The segmental bronchi further subdivide to supply the various portions of the segments.

Table 5-1 Nomenclature Adopted by the Ad Hoc International Committee Meeting at the Time of the International Congress of Otorhinolaryngology in 1949 | |||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Table 5-2 Bronchopulmonary Segmental Nomenclature and Numerical Designations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Proceeding distally from the takeoff of the upper-lobe bronchus, the primary bronchus is known as the bronchus intermedius, over which the mainstem pulmonary artery crosses, thus giving rise to the term epiarterial bronchus to designate the right-upper-lobe bronchus. After a distance of about 1.7 to 2.0 cm, the middle-lobe bronchus arises from the anterior surface of the bronchus intermedius. It varies in length between 1.2 and 2.2 cm before it bifurcates into lateral and medial branches. The superior segmental bronchus of the lower lobe arises from the posterior wall of the bronchus intermedius, slightly distal to the middle-lobe bronchus. The superior segment is called the posterior accessory lobe when a fissure is present. This bronchus most often arises as a single branch and divides into three rami, usually by bifurcation or rarely by trifurcation. Distal to the superior bronchus, the basal stem bronchus sends off segmental bronchi to the medial (the inferior accessory lobe when a fissure is present), anterior, lateral, and posterior basal segments. The medial basal bronchus arises anteromedially and is distributed to the anterior and paravertebral surfaces of the lower lobe. The anterior basal branch arises on the anterolateral aspect of the basal trunk about 2 cm distal to the superior segmental bronchus

and divides into two major rami. The lateral basal bronchus and the posterior basal bronchus most often arise as a common stem. Each of these bronchi, in turn, divides typically into two major subdivisions (Fig. 5-7).

and divides into two major rami. The lateral basal bronchus and the posterior basal bronchus most often arise as a common stem. Each of these bronchi, in turn, divides typically into two major subdivisions (Fig. 5-7).

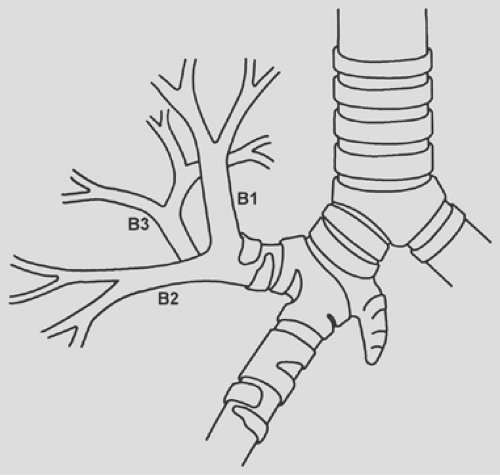

Numerous variations occur, but the basic pattern encountered is as described. Infrequently, the upper-lobe bronchus on the right undergoes two separate bifurcations to form the three bronchopulmonary segments. Of more interest is the rare occurrence of a tracheal bronchus that arises most commonly 2 cm above or at the level of the tracheal carina. A tracheal bronchus is estimated to be present in 0.1% to 2.0% of human tracheobronchial trees, depending on the manner of diagnosis and the population group studied, as noted by Barat and Konrad4 in 1987. The tracheal bronchus occurs for all practical purposes exclusively on the right. Two major types exist: one consists of the right-upper-lobe bronchus and its divisions and the other consists only of the apical segmental bronchus (ectopic or supernumerary) (Fig. 5-8). These, as well as other less common variations, have been described in the report by McLaughlin and colleagues.48 Le Roux42 and Atwell2 also discussed these anomalies. The diameter of the tracheal bronchus ranges between 0.5 and 1.0 cm and its length between 0.6 and 2.0 cm. Infrequently an anomalous bronchus arises from the medial wall of the bronchus intermedius. It is found in 0.09% to 0.5% of the general population. It may occur at any level of the bronchus intermedius. Most often, however, it occurs at or just distal to the level and opposite to the orifice of the right upper lobe (Fig. 5-9). A few may arise more distally toward the level of the takeoff of the middle-lobe bronchus. The anomalous bronchus, designated as the accessory cardiac bronchus by Brock,15 may be only a short blind stump or diverticulum without any distal branches. About half the time it is present, according to McGuinness and associates,47 the accessory cardiac bronchus may have a number of rudimentary or nearly normal branches associated with variable amounts of lung parenchyma. The length of this anomalous bronchus, according to Daskalakis,21 may vary from

0.5 to 5.0 cm. On a rare occasion, two accessory cardiac bronchi may be present, as noted by Mangiulea and Stinghe.46 These authors, as well as Jackson and Littleton,35 also noted that an accessory cardiac bronchus may be found in association with a tracheal bronchus. The clinical findings and significance of a tracheal bronchus and an accessory cardiac bronchus are presented later in this chapter. The variations in the middle-lobe bronchus and its branchings, other than an occasional superoinferior spatial relationship of the segments rather than lateral and medial arrangements, are of little interest. In the division of the lower-lobe bronchus, the presence of a subsuperior or an accessory subsuperior bronchus is a frequent finding. One to three such bronchi may be identified.

0.5 to 5.0 cm. On a rare occasion, two accessory cardiac bronchi may be present, as noted by Mangiulea and Stinghe.46 These authors, as well as Jackson and Littleton,35 also noted that an accessory cardiac bronchus may be found in association with a tracheal bronchus. The clinical findings and significance of a tracheal bronchus and an accessory cardiac bronchus are presented later in this chapter. The variations in the middle-lobe bronchus and its branchings, other than an occasional superoinferior spatial relationship of the segments rather than lateral and medial arrangements, are of little interest. In the division of the lower-lobe bronchus, the presence of a subsuperior or an accessory subsuperior bronchus is a frequent finding. One to three such bronchi may be identified.

Left Bronchial Tree

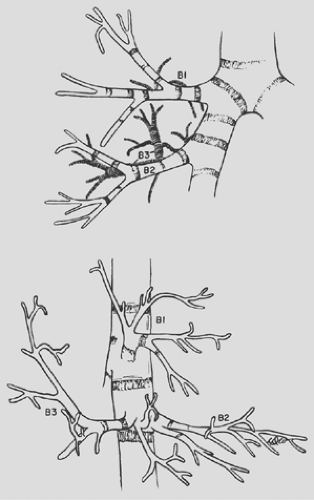

The left main bronchus is longer than the right, and its first branch arises anterolaterally as the left-upper-lobe bronchus about 4 to 6 cm distal to the tracheal carina. This bronchus is about 1.0 to 1.5 cm long and divides into superior and inferior (lingular) branches. The superior division ascends and the inferior one descends. The superior branch most often bifurcates into an apical posterior segmental bronchus and an anterior segmental bronchus. Occasionally, the anterior segment migrates inferiorly to create a trifurcate pattern. The inferior or lingular bronchus, the analog of the middle lobe, is variable in length (1–2 cm) and subsequently divides into superior and inferior divisions, the former of which, in turn, subdivides into posterior and inferior rami.

About 0.5 cm distal to the left-upper-lobe orifice, the lower-lobe stem bronchus gives off its first branch, the superior segmental bronchus. This bronchus arises posteriorly and bifurcates in most instances, but trifurcation does occur. After giving off the superior branch, the basal trunk continues for an average distance of 1.5 cm as a single trunk. The bronchus then usually bifurcates into an anteromedial basal segmental bronchus and a common stem bronchus for the lateral basal and posterior basal bronchi. These branches further subdivide into numerous rami for their respective segments (Fig. 5-10).

On the left side, the common variations are in the distribution of the segmental bronchi from the superior and inferior divisions of the left-upper-lobe bronchus and the presence of a subsuperior or accessory subsuperior bronchus arising from the lower-lobe bronchus. Many of these deviations from normal have little clinical importance but are significant at the time of surgical resection of the various portions of the lungs.

A rare anomaly—a so-called bridging bronchus—has been described on rare occasions. The bridging bronchus arises from the left mainstem bronchus and crosses the mediastinum to supply the right lower lobe and, at times, a portion of the middle lobe (Fig 5.11). This anomalous bronchus was first reported by Gonzalez-Crussi and associates29 in 1976 (see “Clinical Findings and Significance of Tracheobronchial Anomalies” later in this chapter). This occurrence may be frequently associated with either a pulmonary venous or a pulmonary arterial abnormality.

Bronchial Isomerism

According to Fraser and coauthors,26 “bronchial isomerism is characterized by a pattern of bronchial branching and pulmonary lobe formation that is identical in the two lungs.” The incidence of this anomaly is unknown. Suen and colleagues73 presented a computed tomography (CT) image and two endoscopic illustrations. The branching pattern of the right bronchial tree was the mirror image of the normal left bronchial tree. The clinical significance of this event is its frequent association with other anomalies of other organs.

Absence of a Lobar Bronchus

The congenital absence of a lobar bronchus is rare. It appears that only 11 cases have been reported in the literature. The absence may be discovered in an infant but has been more commonly identified in adult patients. In the latter, the anomaly has been identified by bronchoscopy or bronchography, at the time of a pulmonary procedure, or infrequently at necroscopy. Ferguson and Neuhausen25 reported a patient with only a right-upper-lobe bronchus with the absence of a middle-lobe- and right-lower-lobe bronchus at bronchoscopy. Morton and associates56 reported, in 1950, the agenesis of the right-upper and middle-lobe bronchi in each of two patients. Storey and Marranooni72 reported the absence of a left lower lobe in a young adult man. Subsequently, in 1967, Atwell3 at the Overholt Thoracic Clinic described the absence of four lobar bronchi (one of the right upper lobe and three of the left upper lobe) in a series of 1,200 consecutive, complete, bilateral bronchograms—an overall incidence of 0.16%.

Landing and Wells41 presented a case in a 2-month-old infant with hypoplasia of the right lung as well as absence of the middle-lobe bronchus. These authors also reported a second infant with a scimitar syndrome associated with an absence of the right-upper-lobe bronchus. Both these infants had multiple other congenital defects, and the lobar bronchial agenesis was confirmed at the time of autopsy.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree