Figure 34.1

There are several approaches to surgery of the SVC, the choice of which may depend on the surgeon’s preferences. However, in deciding which one to use, the surgeon should consider the type of lung resection to be performed, the size of the lesion, and whether the innominate veins are involved. Surgical access to the SVC is possible via either a right lateral thoracotomy in the fourth or fifth intercostal space or an anterior incision such as a sternotomy or hemi-clamshell thoracotomy. Although the right thoracotomy yields the best exposure of the right hilum and excellent visualization of the SVC and the right atrium, it renders the dissection, control, and revascularization of the left brachiocephalic vein technically demanding. The incision usually is a muscle-sparing lateral thoracotomy made from the anterior edge of the latissimus dorsi to the posterior edge of the greater pectoral muscle in the fourth or fifth right intercostal space (a). In female patients, the axillomammary fold is cosmetically preferred. Through this approach, the lung resection (right upper lobectomy, sleeve lobectomy, or sleeve pneumonectomy) associated with lymph node dissection is performed easily. For NSCLC invading the origin of the SVC or for anterior mediastinal tumors involving the brachiocephalic vein, a median sternotomy (b) or a hemi-clamshell incision (c) is preferred. Although the median sternotomy affords the best approach for safe control of the entire length of the SVC and innominate veins, it does not offer the easiest exposure for pulmonary resection. Patients should be ventilated through a double-lumen tube to obtain one-lung ventilation. Continuous arterial and venous pressure measurements are essential. A radial artery line should be inserted transcutaneously to monitor decreases in systemic pressure caused by reduced venous return to the right side of the heart during venous clamping. A catheter is inserted into the cephalic or right internal jugular vein to monitor the venous pressure in the cephalic region. The arterial and venous lines are essential to monitor and maintain the physiologic arteriovenous brain parenchymal gradient. Electrocardiography should be used to monitor cardiac electrophysiologic alterations during venous clamping, because the distal clamp may be too close to the sinus node. A central venous catheter is placed in the femoral vein to achieve volume expansion during venous clamping and is removed 48–72 h postoperatively. After intubation, the patient is placed in the lateral position with the back moved toward the edge of the table. A soft roll is placed under the controlateral chest wall, and the head is padded in axial alignment. The sterile field is prepared to include the axilla, the anterior chest across the sternum and neck to the level of the mandible, and the spine. The surgeon stands to the patient’s back, with the first assistant across the table and the second assistant cephalad to the surgeon. A mechanical arm holder is preferred and secured to the side bar of the bed

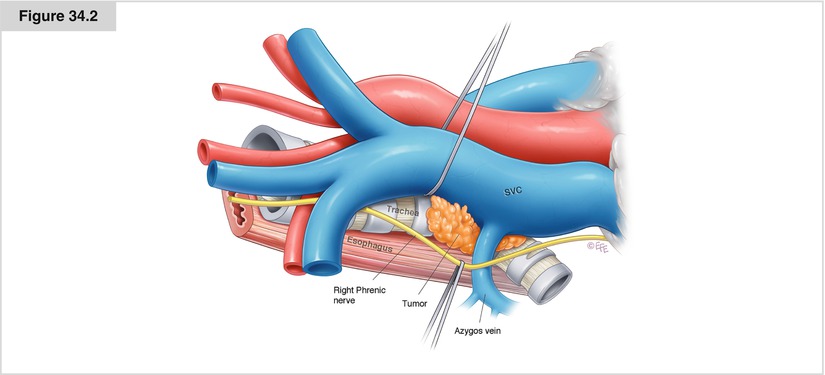

Figure 34.2

An understanding of the anatomy of the SVC is essential to the performance of surgical procedures on this vessel. The SVC originates behind the first right costal cartilage from the confluence of the right and left innominate veins. It extends vertically for approximately 7 cm to enter the posterior part of the right atrium. It has a transverse diameter of 2 cm. The right phrenic nerve courses along the SVC immediately under the right pleura. The SVC receives only one collateral branch, the azygos vein, which runs from the spine anteriorly, arching over the right main bronchus. The SVC is adjacent to the thymus anteriorly, the right paratracheal lymph nodes posteriorly, and the right main pulmonary artery inferiorly. The medial area lying between the intrapericardial SVC and the ascending aorta includes an extrapericardial region, where the origin of the right main bronchus lies, and the anterior aspect of the right pulmonary artery, which lies behind the SVC and the right orifice of the Thiele sinus. NSCLC involving the SVC frequently invades at or near the caval–azygos vein junction. Depending on the cancer’s location, it also may involve the anterior trunk of the right pulmonary artery, the right phrenic nerve, and the right mainstem or upper lobe bronchus. The tissue planes often are lost between the tumor and the SVC wall. One should avoid the temptation to dissect the tumor from the SVC, as troublesome bleeding may occur in the absence of appropriate initial vascular control maneuvers. Effort should be made to obtain proximal control of the SVC, to dissect and control the innominate vein, and to identify whether the phrenic nerve can be preserved. The superior pulmonary vein rarely is involved by the tumor, and division of this vessel is a logical first maneuver that provides exposure to the right pulmonary artery and associated arterial trunk. If the tumor involves the distal portion of the SVC or the pulmonary artery, then intrapericardial control of the right pulmonary artery should be obtained between the SVC and the ascending aorta. These maneuvers permit access to the anterolateral aspect of the distal SVC just beneath the azygos vein, where vascular control of the distal SVC can now be obtained

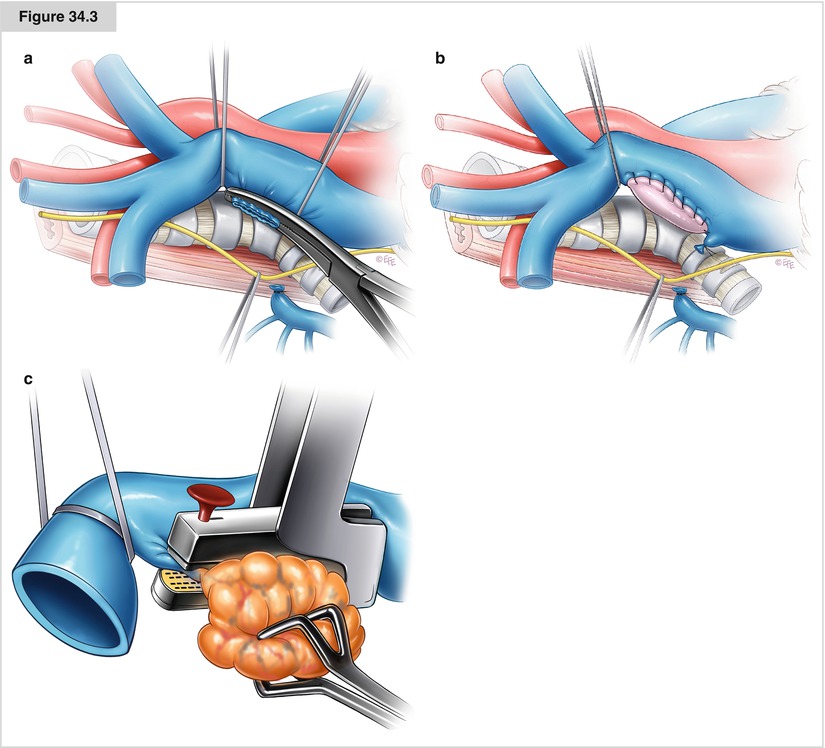

Figure 34.3

(a–c) If less than 50 % of the SVC circumference is infiltrated laterally, a partial resection is possible. The vascular repair may be accomplished either by direct suture with 5-0 polypropylene after a vascular clamp is placed inferiorly to superiorly (a) or by interposition of an autologous (pericardial or vein) or a heterologous (bovine pericardium) patch (b). This prevents narrowing or kinking of the SVC with a long primary repair suture line. When a patch is used, sutures are placed at the superior and inferior aspects of the defect and patch, running along the anterior and posterior walls of the defect to close it. Before placing any clamp, it is preferable to mobilize the SVC as much as possible, particularly posteriorly and medially. Division of the azygos vein facilitates mobilization of the SVC. In some cases, a stapler with a vascular cartridge may be used before the infiltrated portion of the SVC is cut (c). Intraoperative clamping of less than 50 % of the SVC circumference usually is not associated with any significant hemodynamic imbalance. If partial SVC resection is required, then there is no indication for administering systemic heparin

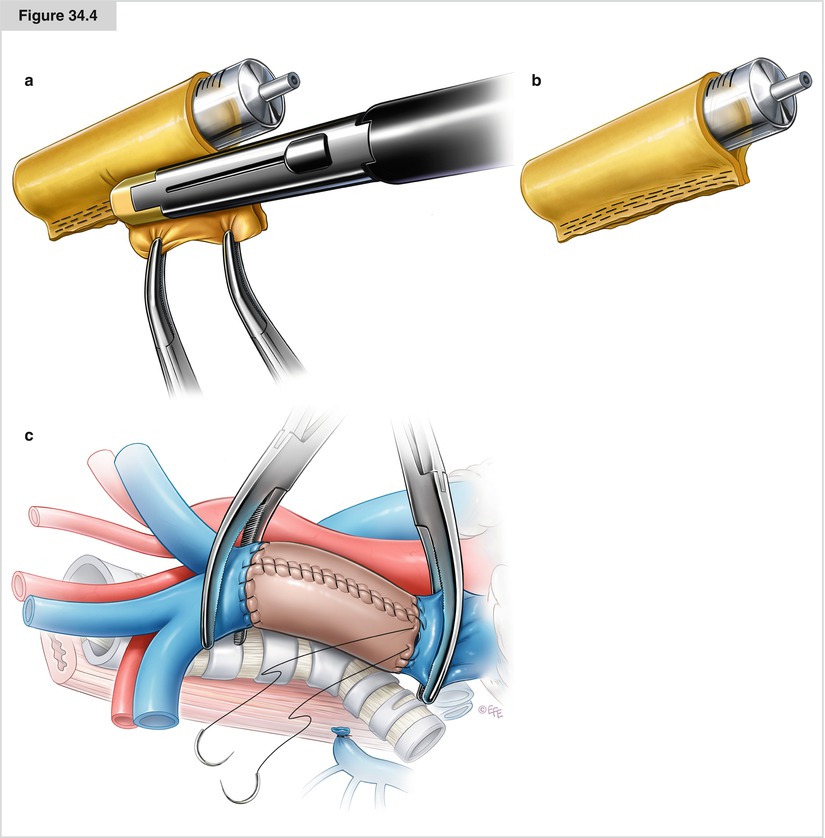

Figure 34.4

(a–c) If the tumor involves more than 50 % of the SVC circumference, the portion of SVC involved should be resected and reconstructed with either a PTFE graft or an autologous pericardial tube. PTFE grafts used for SVC reconstruction have some disadvantages, including the need for postoperative anticoagulation and the risk of infection and thrombosis. Often, the amount of autologous pericardium may be insufficient to construct a long tube. We advocate the use of a custom-made bovine pericardial prosthesis (a, b), which is advantageous because it is biocompatible and easy to handle, does not require anticoagulation, is thicker than the human graft, does not shrink, and retains suture better than fresh pericardium. Moreover, this material carries less risk of infection and thrombosis and produces excellent results in terms of graft patency. After intravenous heparin is administered, the SVC is clamped proximally (at the brachiocephalic vein confluence) and distally (at the cavoatrial junction) and then resected. In anticipation of SVC clamping and resecting, the patient’s bed should be placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position. The graft is brought onto the operative field. The proximal anastomosis is performed first using a 5–0 polypropylene suture starting at the posterior aspect of the prosthesis in an in-to-outside fashion. The anastomosis is then tested for evidence of significant leakage, which may require a repair suture. The distal anastomosis is then performed the same way. Before the distal suture line is tied, the proximal clamp is released and the prosthesis is flushed with heparinized saline solution and de-aired. The distal clamp is removed and the knot secured (c). The surgeon must ensure there is an adequate length of proximal and distal SVC from the clamps to sew the graft in place. It is imperative that there be no tension on the graft. Graft redundancy, particularly if a bovine or autologous pericardial graft is used, may result in torsion or kinking of the graft. Intraoperative total clamping is relatively well tolerated for around 30–60 min; longer periods of clamping of the return venous flow may result in potentially fatal cerebral edema or postoperative neurologic deficits. After a few minutes of clamping, head and neck edema with cyanosis and petechiae may develop, but these signs are reversible after unclamping. Maneuvers to minimize hemodynamic compromise are as follows: (a) intraoperative shunt procedures via placement of an intraluminal or extraluminal shunt, (b) cardiopulmonary bypass (used rarely and mainly for giant mediastinal tumors), and cross-clamping (used most commonly). Cross-clamping may lead to cranial venous hypertension and systemic hypotension owing to impaired venous return, thus reducing cerebral blood flow, with possible adverse neurologic consequences. Increased venous pressure is counteracted with vasoactive fluids and drugs that increase arterial pressure. Rapid SVC substitution (with complete heparinization, 0.5–1 mg/kg) keeps cross-clamping times as short as possible. Cephalic venous and systemic arterial pressures are monitored continuously during the operation, as are cardiac filling and hemodynamic changes during clamping (preferably by transesophageal ultrasonography). A double-lumen catheter placed in the femoral veins allows the necessary vascular filling to be obtained during clamping

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree