Figure 5.1

Deep inhalation or total intravenous anesthesia is selected to avoid muscle relaxation before the airway is secured. No advantage is gained from dilating a stricture slated to be resected, and the trachea is intubated with a small (5- or 6-mm) endotracheal tube. The inset shows the patient placed in the supine position with the arms alongside the trunk, elevating the shoulders and maximally extending the neck. A short collar incision is made. Subplatysmal flaps are created to expose the anterior neck from the thyroid cartilage to the manubrium

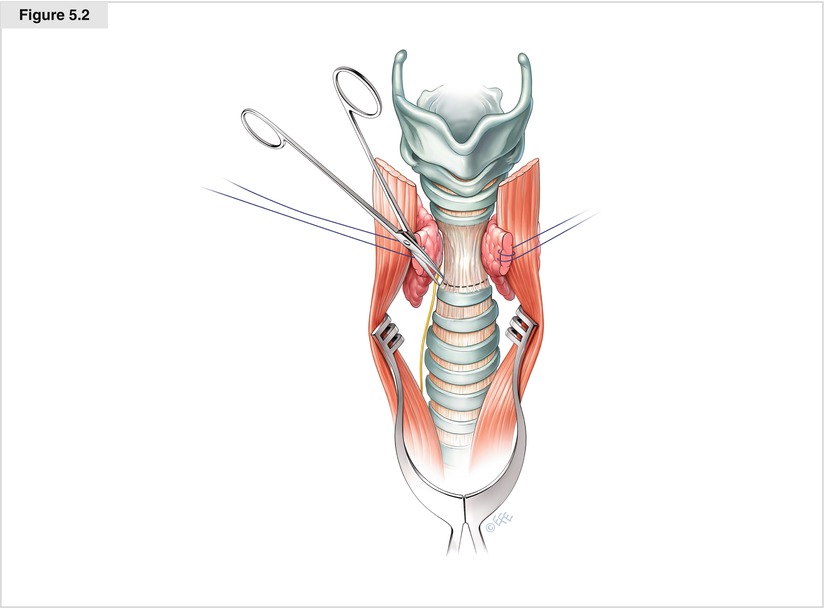

Figure 5.2

The strap muscles are separated, and the thyroid isthmus is divided. Gelpi retractors maintain the exposure. The length of the avascular anterior pretracheal plane to the carina and, as dictated by tension, the plane beyond is mobilized, leaving the lateral vascular attachments intact. There may be scarring from a previous tracheostomy. This maneuver reduces anastomotic tension and therefore is conducted carefully and completely. Circumferential dissection of the trachea at the lower end of the stricture is carried out to prepare for tracheal division. The scissors are pointed toward the tracheal wall to exclude peritracheal tissues and recurrent laryngeal nerves

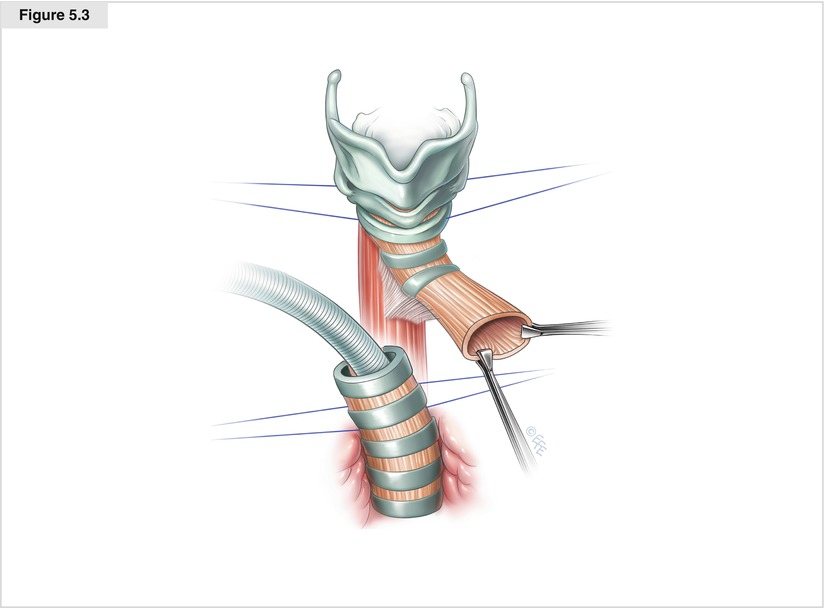

Figure 5.3

The trachea is divided at the lower end of the stricture. The destroyed cartilage in postintubation injuries, as shown here, points to the level of airway division. In idiopathic strictures with an intact outside wall, fiberoptic bronchoscopy can identify the appropriate level of inferior division through placement of a 25-gauge needle through the anterior trachea. Cross-field ventilation is established with sterile anesthesia tubing connected to an armored 7-mm tracheal tube. The orotracheal tube is retracted above the vocal cords, and the upper airway is inspected. The tracheal segment attached to the larynx is excised sharply, keeping the plane of dissection close to the wall

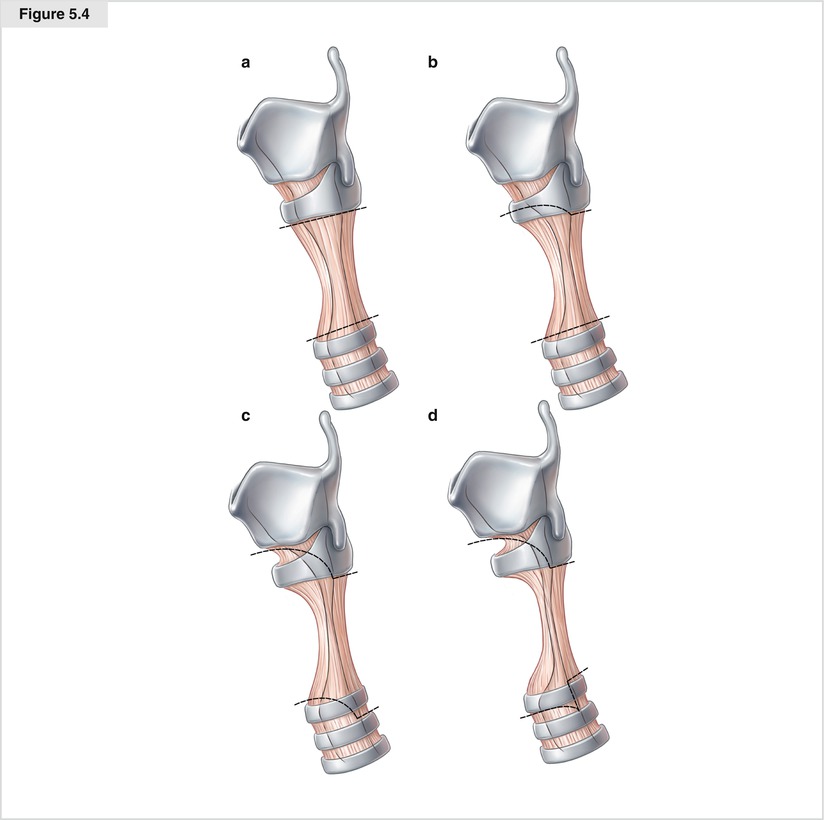

Figure 5.4

The laryngeal lumen is inspected from below to determine the appropriate level for division of the airway above the stricture. Shown here for clarification are four lateral views with the increasingly cephalad extent of subglottic strictures. (a) Anterior stomal narrowing terminating below the cricoid, a purely tracheal stricture. In this case, an anterior horizontal incision below the cricoid exposes a normal subglottic diameter, and the trachea is divided below the cricoid Plate. (b) Anterior injury involves the lower portion of the cricoid, and oblique excision of the stricture leaves the superior arch of the cartilage intact. (c) The anterior cricoid is destroyed, but the posterior and lateral subglottic mucosa remains normal. The surgeon excises the anterior scar preserving the lateral cricoid laminae both to anchor the traction sutures and to provide anterior projection to the reconstructed larynx. A sloping incision connects to the lower margin of the posterior cricoid plate; close attention is directed to the course of the recurrent nerves as they enter the plate from below. (d) Demonstrates the situation of a high circumferential stricture; the vestibule after oblique incision into the subglottic space remains narrowed, indicating the need for excision and resurfacing with a flap of membranous wall. Safe, unhurried dissection is advisable when the larynx is divided, as its result influences laryngeal function after operation

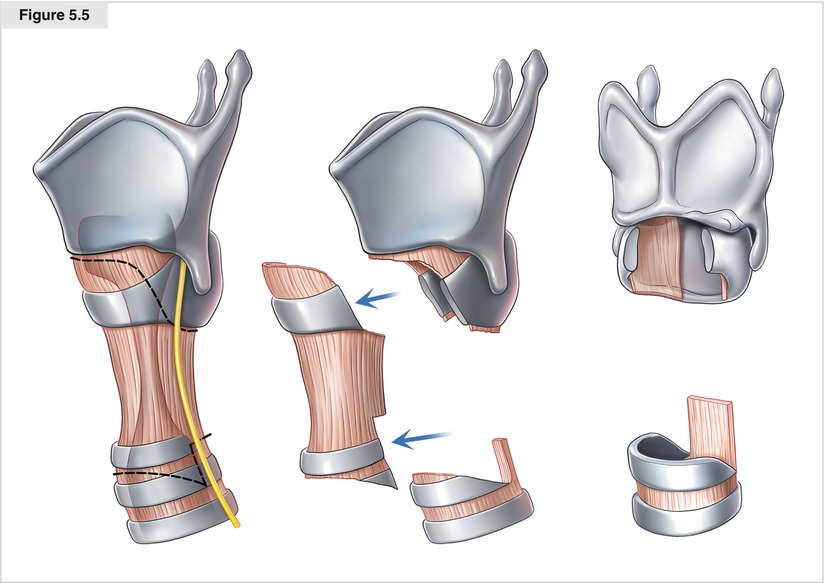

Figure 5.5

Both the larynx and trachea are tailored carefully in preparation for anastomosis. If its mucosa is abnormal and thickened, the anterior cricoid arch is excised with the knife to open an adequate vestibule, leaving the lateral cartilage intact. The mucosa overlying the posterior cricoid plate also is excised when obstructing the lumen, as shown here. This posterior excision bares the cricoid plate and must be covered with a mucosal tracheal flap. The trachea is shaped to fit the laryngeal defect. An anterior prow is created, sloping its outline toward the membranous wall and leaving a long membranous wall to serve as a flap

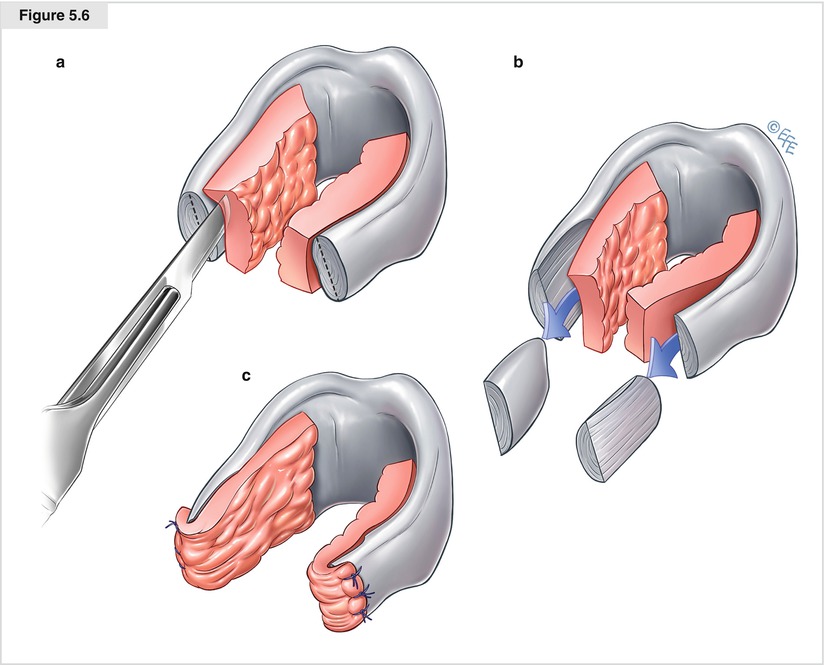

Figure 5.6

The lateral subglottic mucosa must be preserved to cover the lateral cartilage. Pronounced narrowing of the airway lumen is caused by submucosal thickening in some patients with idiopathic stenosis. Lateral narrowing is relieved by excision of the submucosa with the knife and partial resection of the lateral cricoid. The mucosal flap is elevated sharply with a superior and posterior base (a). The submucosa and no more than half the thickness of the cricoid laminae are excised (b). Lateral cricoplasty is completed by tacking the mucosa over the lateral cricoid to the outside perichondrium with 5-0 chromic catgut sutures (c). The subglottic airway thus is enlarged, at times by as much as 5 or 6 mm (Liberman and Mathisen 2009).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree