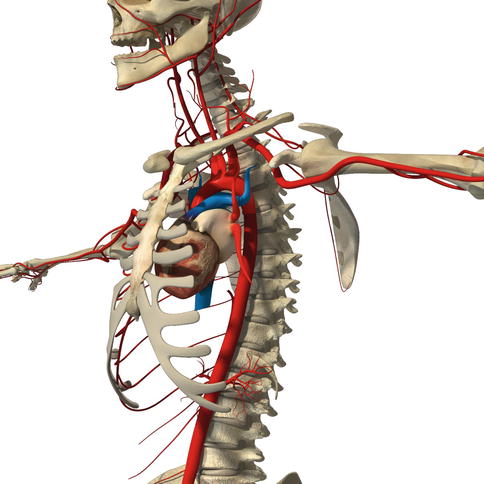

Fig. 14.1

Divisions of the subclavian artery and its key branches. The first segment of the subclavian artery is medial to the anterior scalene muscle and typically gives rise to three significant vessels: the vertebral artery, the internal mammary artery, and the thyrocervical trunk. The second segment lies deep to the anterior scalene and typically gives rise to the costocervical trunk. The third segment is lateral to the anterior scalene muscle and gives origin to the dorsal scapular artery. The subclavian artery becomes the axillary artery at the medial border of the pectoralis minor muscle

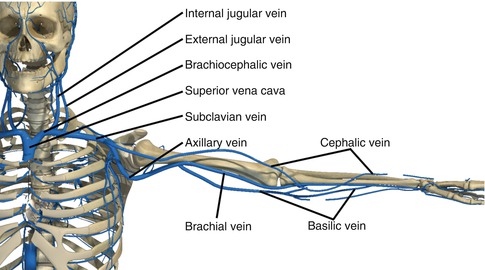

Fig. 14.2

Lateral view of the aorta. The arch of the aorta does not curve from right to left as depicted in many texts. Instead, the arch curves from anterior to posterior

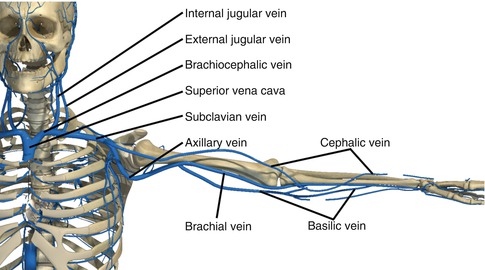

The subclavian vein is the continuation of the axillary vein that arises from the cephalic, brachial, and basilic veins of the arm (Fig. 14.3). The cephalic vein traverses the lateral side of the arm from the hand to the shoulder. The basilic vein traverses the medial side of the arm. The brachial or deep vein of the arm joins the basilic vein to become the axillary vein. In the shoulder, the cephalic vein pierces the deltopectoral fascia and empties into the axillary vein. After the cephalic vein joins the axillary vein, it becomes the subclavian vein. The subclavian vein extends from the outer border of the first rib to the medial border of the anterior scalene muscle. Here, the internal jugular vein joins the subclavian vein, and it is now referred to as the brachiocephalic vein. Once the brachiocephalic vein joins its counterpart from the other side, it becomes the superior vena cava. The subclavian vein lies anterior to the anterior scalene muscle. The subclavian artery lies posterior to the anterior scalene muscle. Hence, the anterior scalene muscle is sandwiched between the subclavian vein and artery.

Fig. 14.3

Major veins of the head, neck, and upper extremity

14.4 Clinical Assessment

The initial assessment and management should follow standard Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocols. After determining that the patient has an adequate airway, the next priority is assessment of labored breathing and adequate breath sounds. Air bubbling through a wound and subcutaneous emphysema may indicate a pneumothorax. A thorough pulse exam should be performed to assess circulation. The absence of a pulse does not necessarily mean that there is an arterial injury, and the presence of a pulse does not necessarily mean that there is no injury. Nonetheless, the presence or absence of a pulse upon admission should be documented.

A focused neurologic exam should be obtained, with particular attention to neurologic compromise of the ipsilateral upper extremity. Because of the close anatomical relationship of the neurovascular structures, the brachial plexus is injured in about one-third of patients with subclavian vessel injury. Therefore the axillary, median, radial, ulnar, and musculocutaneous nerve exams should be documented. Plexus injuries can be caused by penetrating injuries that directly transect nerve roots or by blunt injuries that result in shear or traction forces [1–3].

14.5 Initial Management

Once the exam is complete, the critical decision point in a patient with a suspected subclavian vessel injury is determining if the patient is stable or unstable. Hemodynamically unstable patients are transported to the operating room without delay, and those in extremis require an immediate anterolateral ED thoracotomy.

The second most important management decision is to ensure adequate intravenous access. Intravenous (IV) lines should be inserted on the contralateral side of the injury; as infused fluids via an ipsilateral IV will extravasate from the wound. These patients are at high risk of a massive transfusion, and the blood bank should be notified of such.

The most common physical finding indicative of vascular injury is hematoma formation. Direct pressure should be applied to help control bleeding. Some injuries behind the clavicle will not benefit from direct pressure. A commonly described technique of balloon tamponade with a Foley catheter inserted into the missile tract is often ineffective. Remember the pulse exam is an insensitive sign of subclavian artery injury. Collateral circulation around the shoulder may result in a normal pulse when in fact there is an injury to the artery.

14.6 Diagnostic Testing

Bilateral upper extremity blood pressures should be recorded in all patients with suspected upper extremity vascular injury. A difference of more than 5–10 mmHg should prompt a more thorough evaluation of possible injury sites. A chest x-ray should be obtained. Stable patients with suspected upper extremity vascular injury should undergo computed tomographic angiography (CTA) of the neck, chest, and upper extremity. CTA can be invaluable for identifying the location of injury as well as evaluating the mediastinal vascular and nonvascular structures.

14.7 Endovascular and Operative Management

After a diagnostic work-up on a stable patient, the next step is a therapeutic intervention. This can be pursued in an open or endovascular fashion. Many hospitals are building hybrid operating rooms that allow open or endoluminal management, thus allowing the surgeon to bring a trauma patient directly to the operating theater for diagnostic work-up, endovascular repair, endovascular adjunctive care, or an open operation.

Endovascular options, including balloon tamponade and stent grafting via percutaneous access or in conjunction with open surgical repair, can be life and limb saving. Arterial access is commonly approached percutaneously through the femoral artery, though percutaneous or open brachial approaches can also be utilized and are sometimes necessary in conjunction with the femoral access. Once guide wire traversal through the area of injury has been achieved, a covered stent graft upsized by roughly 10 % of the diameter of adjacent healthy vessel is deployed. Lesions that appear difficult to traverse are sometimes accessed through the brachial vessels because this provides a direct, shorter, less tortuous approach. Pseudoaneurysm, arteriovenous fistula, arterial intimal flap, and lacerations of subclavian vessels have all been treated with endovascular repairs. Endovascular covered stent placement in the appropriate patient eliminates the acute need for surgical dissection, anterolateral thoracotomy, decreasing the risk for injuring structures such as the vagus nerve, recurrent laryngeal nerve, phrenic nerve, and innominate vein. Careful patient selection is necessary, and only focal lesions that can safely be traversed with a guide wire can be approached in this fashion. Contraindications to endovascular repair include a hemodynamically unstable patient, long segmental arterial injury, and insufficient proximal or distal fixation points. Some patients will have an arteriogram that demonstrates a contraindication to an endovascular repair and will require an open operation, in which case proximal balloon occlusion can be useful [4–7].

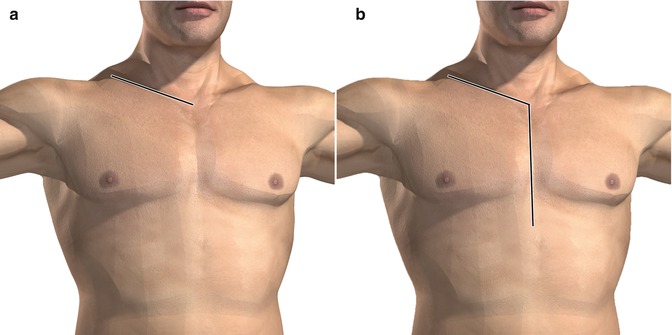

For patients that do require an open surgical approach, the surgeon should be able to respond quickly with a systematic approach in mind for exposure. The right and left subclavian arteries are exposed via different incisions and patient positioning depending on the location of injury with respect to the vertebral artery. For right-sided injury distal to the vertebral artery, the preferred method is to start with a right supraclavicular incision. This incision starts at the sternoclavicular junction and extends over the length of the clavicle (Fig. 14.4). Should additional exposure be needed, such as those with injury proximal to the vertebral, median sternotomy is performed utilizing a Lebsche knife or sternal saw (Fig. 14.5). The dissection and exposure of the right subclavian artery begins first by dissecting and removing the underlying scalene fat pad. Once it is removed, the phrenic nerve must be identified. This is a key anatomical landmark that must be preserved. The nerve courses lateral to medial along the anterior scalene muscle. The nerve can be isolated with a vessel loop and gently retracted out of the way. The anterior scalene muscle should be cut as low as possible, and the subclavian artery will be found behind it.

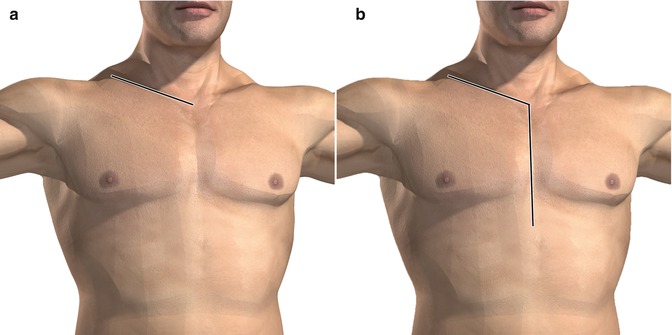

Fig. 14.4

(a) Clavicular incision for accessing the innominate, common carotid, and subclavian arteries. (b) Median sternotomy extension for more proximal access. This incision starts at the sternoclavicular junction and extends over the length of the clavicle

Fig. 14.5

Lebsche knife used for completing a median sternotomy

The choice of surgical incision for left-sided injury is more difficult due to the orientation of the aorta and the very posterior origin of the left subclavian artery. There are three ways to expose the left subclavian artery – a supraclavicular incision with clavicle resection, a left anterolateral thoracotomy, and a sternoclavicular flap (trapdoor). The supraclavicular incision is made one fingerbreadth above and parallel to the clavicle extending from the sternal notch to the lateral end of the clavicle (Fig. 14.6). Cautery is used to score the clavicle, a periosteal elevator is used to peel the periosteum off the clavicle in a circumferential fashion, and the clavicle is divided in the middle with bone cutters. Once the clavicle is cut, it can be grabbed with a towel clip and removed from its bed. The clavicle is then removed from the sternum. The clavicle can be resected with surprisingly little disability and deformity. The clavicle does not need reconstruction with orthopedic plating. Dissection of the left subclavian artery commences similar to as described above for the right. A supraclavicular incision is adequate if the injury is distal to the vertebral [8–10].