Subclavian and Axillary Artery Aneurysms

AMIT JAIN and KENNETH J. CHERRY

Presentation

A 56-year-old Caucasian female with a past medical history of Marfan’s syndrome presented to clinic for evaluation of painless swelling below her left clavicle. She noticed this swelling a few months previously. She had a strong family history of Marfan’s syndrome involving her father and 2 of her 13 siblings. She denied any tingling, numbness, or cold sensation in her left upper extremity. She had gastroesophageal reflux disease with hiatal hernia, controlled with medications, and was status post inguinal hernia repair and bilateral lens implants. She had an ECHO 6 months earlier that showed a normal heart and aortic root. On physical examination, she had intact radial, ulnar, and brachial pulses with equal and normal blood pressures in both arms. There was a pulsatile, expansile painless swelling in the left infraclavicular region, measuring approximately 3 × 4 cm. Motor and sensory functions of the left upper extremity were normal.

Differential Diagnosis

A supra or infraclavicular pulsatile and expansile mass raises the possibility of subclavian or axillary artery aneurysm. Thoracic outlet syndrome, especially with a cervical rib, may be an etiology. In the presence of a cervical rib, the subclavian pulse is often palpable high in the neck rather than in its usual “subclavian” position. Poststenotic dilatation of the subclavian artery beyond a mechanical thoracic outlet obstruction or chronic soft and bony tissue damage to the artery is seen in this situation.

A pseudoaneurysm may develop at access sites in the axillary artery for central line and placement of cannulas during cardiac operations. A pseudoaneurysm may also form at the proximal anastomotic site of an axillary-femoral bypass graft and may present as a pulsatile swelling in the infraclavicular area and deltopectoral groove. These pseudoaneurysms may or may not be infected. Connective tissue disorders, like Marfan’s syndrome and Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, may present with true and false aneurysms of the subclavian or axillary arteries. Endovascular interventions may cause pseudoaneurysms, as may noniatrogenic blunt and penetrating trauma.

Workup

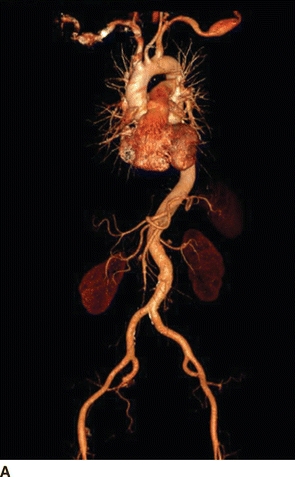

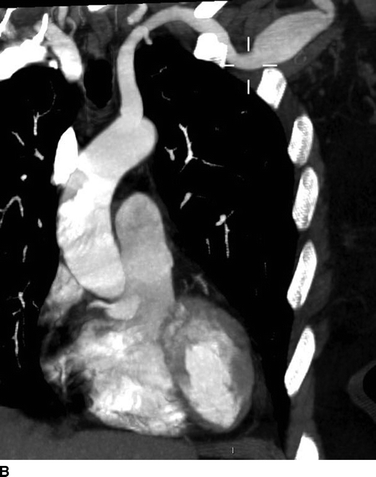

Given the history of Marfan’s syndrome in this patient with a palpable, painless, pulsatile, and expansile mass in the left infraclavicular region and a high suspicion for aneurysm, a computed tomography angiogram (CTA) was obtained. CTA revealed a broad fusiform aneurysm of the left axillary artery with maximal transverse diameter of 2.4 cm over a 4.3-cm long segment (Fig. 1A and B). There was a small 1.8-cm fusiform aneurysm of the contralateral axillary artery over a 2.0-cm length. The rest of the vessels in the chest, abdomen, and pelvis were normal.

FIGURE 1 Preoperative CT angiogram with 3D (A) and 2D MPR (B) reconstructions showing left axillary artery fusiform aneurysm.

Were there acute limb ischemia secondary to macro or microembolism from this axillary aneurysm, a traditional arteriogram might have been indicated to ascertain the degree of forearm and digital ischemia. Macroembolism might also be treated with lysis simultaneously.

Diagnosis

A 2.4-cm true left axillary artery aneurysm secondary to Marfan’s syndrome was diagnosed.

Discussion

Subclavian and axillary artery aneurysms are rare, accounting for only about 1% of all peripheral arterial aneurysms. Of these, more than 85% involve the subclavian artery. Aneurysms of the proximal subclavian artery are usually secondary to “atherosclerotic” degenerational disease. Aneurysms of the distal subclavian artery and axillary artery are frequently secondary to thoracic outlet syndrome. Crutch trauma is the etiology in approximately 50% of axillary artery aneurysms with atherosclerosis, infection, fibromuscular dysplasia, dissection, and connective tissue disorder, like Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, comprising the other etiologies. In addition to these entities, aneurysms of these vessels may be seen in patients with various types of inflammatory arteritis, like Takayasu’s and temporal arteritis.

Most subclavian and axillary artery aneurysms are symptomatic with about 10% of cases asymptomatic at presentation. Symptoms are usually secondary to compression of adjacent structures by the aneurysm or to ischemia from distal embolization. Rupture is rare but can be seen with large aneurysms of the proximal subclavian artery. About two thirds of symptomatic patients present with thrombosis of the aneurysm or a distal macro- or microembolization, causing hand or digit ischemia. Chronic ischemia may present as weakness and easy fatigability of the upper extremity with absent radial or ulnar pulses. Large proximal subclavian artery aneurysms may cause compression of the superior vena cava (facial swelling), sympathetic chain (Horner’s syndrome), and/or recurrent laryngeal nerve (hoarseness). Patients may also present with shoulder, arm, or hand pain and brachial plexus palsy with upper extremity paresthesias. Dysphagia lusoria may be present in the case of an aberrant right subclavian artery. These embryonic arteries are susceptible to aneurysm degeneration. Rupture is dramatic and is one of the few causes of arterial-esophageal fistula. Rupture may occur in the presence of Ehlers-Danlos or Marfan’s syndrome as well.

In patients presenting with ischemic upper extremity symptoms, histories of smoking, sensitivity to cold, and use of vibratory tools should be sought. Buerger’s disease and Raynaud’s syndrome need to be in the differential. Aneurysms of the ulnar artery from blunt trauma to the artery at the hook of the hamate are seen in patients who use their hands as tools of force. These often embolize and cause digital ischemia. Noninvasive vascular lab testing along with duplex examination is useful in differentiating large vessel pathology from small vessel diseases. A hypercoagulable workup, antinuclear antibody, and erythrocyte segmentation rate may be valuable additions to routine complete blood count and serum chemistries.

Bilateral synchronous symptoms are usually an indication of systemic collagen vascular or rheumatologic disease in most cases, and are seldom arterial per se in etiology. The distal subclavian artery and the entire axillary artery may be studied by a duplex ultrasound. Duplex is noninvasive and can effectively rule out the presence of a distal aneurysm and is excellent for follow-up. Ultrasound is of no benefit with proximal subclavian aneurysm. CTA or magnetic resonance angiograms (MRA) are very helpful in operative planning. Conventional angiography is indicated when ischemic digital symptoms are present, as it can assess distal vessels in detail, something CTA and MRA cannot do well. It can simultaneously serve a therapeutic purpose if there is a need for thrombolysis or if the aneurysm is amenable to endovascular treatment.

As most of these aneurysms are symptomatic at presentation, treatment is generally recommended for all cases unless a small aneurysm is detected in patients who can be treated for the underlying causal factor (e.g., thoracic outlet syndrome). Even in those cases, it is rare to leave the artery unattended. Treatment is usually open surgical resection with prosthetic graft bypass for replacement of either the subclavian or the axillary artery.

Surgical Approach

This 56-year-old female with Marfan’s syndrome and a 2.4-cm asymptomatic left axillary artery aneurysm was offered open surgical repair. With the patient in supine position and under general anesthesia, the left arm was extended on an arm board and prepped circumferentially along with the left neck, chest, and shoulder. Through an infraclavicular incision, the pectoralis major muscle fibers were split and the pectoralis minor tendon was divided. The artery was carefully dissected free, proximal and distal to the aneurysm, taking care to avoid injuries to the brachial plexus. Proximal control was obtained just below the clavicle, and the small muscular branches arising directly from the aneurysm were ligated. After heparinization (100 U/kg) to keep the activated clotted time close to 300 seconds, and control of the proximal and distal artery, the aneurysm was opened. Back-bleeding posterior branches were oversewn from within the aneurysm. An 8-mm polyester graft was cut on a slight bevel and anastomosed end to end proximally to the subclavian artery with No. 4-0 Prolene monofilament running suture. A felt strip pledget was used to reinforce the anastomosis given her Marfan’s syndrome. Similarly, the distal anastomosis was performed after cutting the graft to an appropriate length to avoid tension as well as redundancy. Flow was restored and hemostasis achieved after reversing anticoagulation. The wound was closed in layers. The radial and ulnar pulses were restored (Table 1).

Case Conclusion

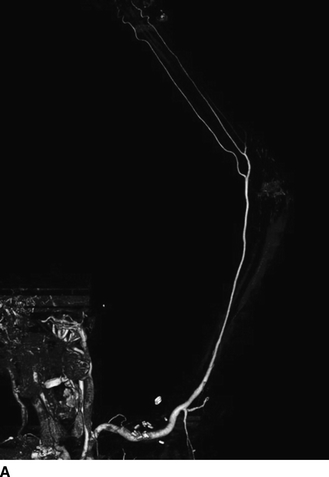

The patient was discharged home on postop day 2 without any complication. On follow-up in the clinic in 6 weeks, a CTA (Fig. 2A and B) was obtained, which showed a patent normal caliber left axillary artery with intact run off.

FIGURE 2 Postoperative follow-up CT angiogram of left upper extremity with 3D (A) and 2D MPR (B) reconstructions showing normal left axillary artery.