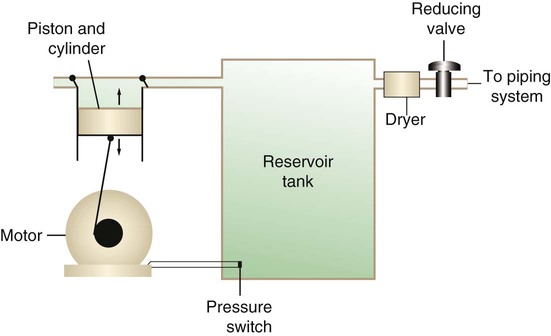

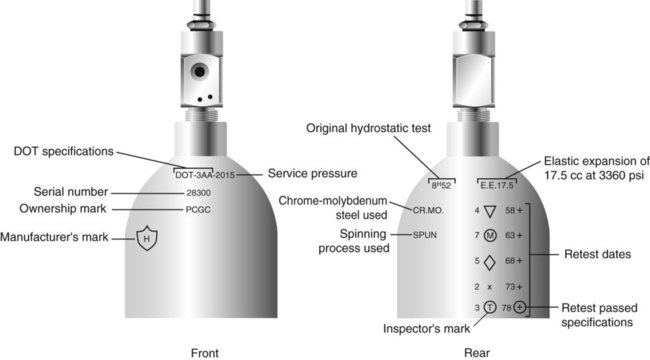

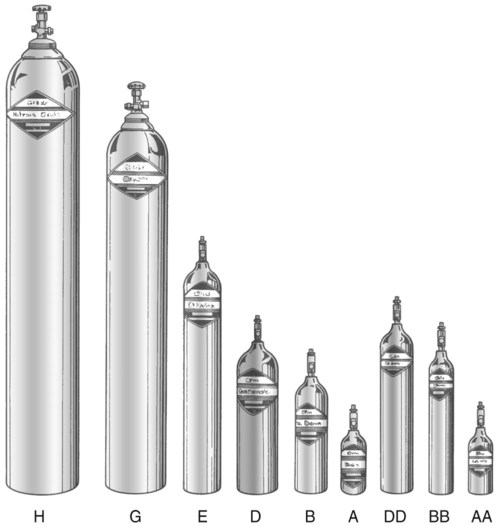

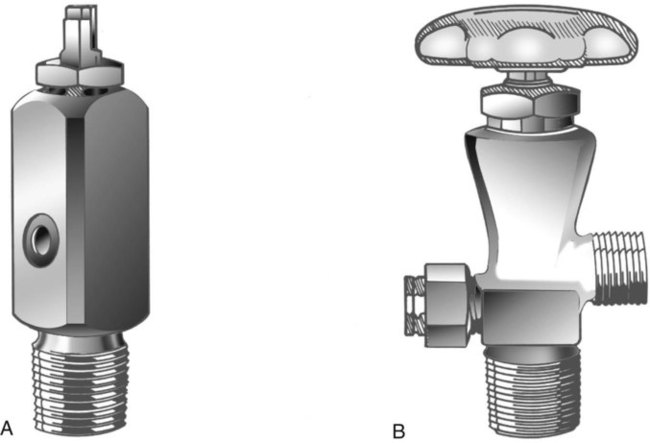

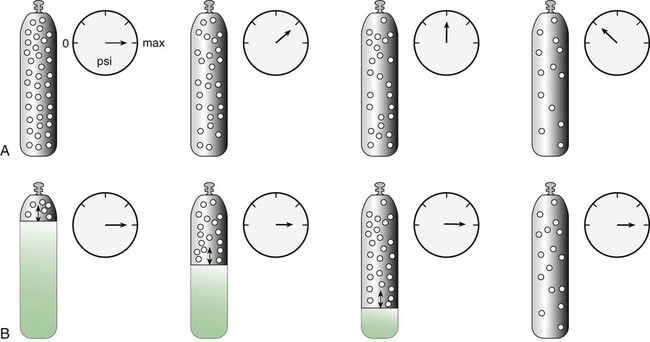

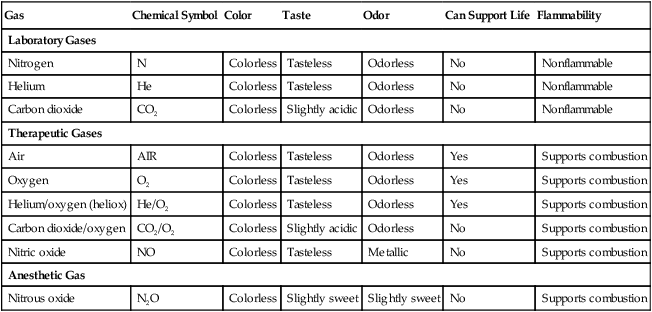

After reading this chapter you will be able to: There are many commercially produced gases, but only a few are used medically (Table 37-1). Medical gases are classified as laboratory gases, therapeutic gases, or anesthetic gases. Laboratory gases are used for equipment calibration and diagnostic testing. Therapeutic gases are used to relieve symptoms and improve oxygenation of patients with hypoxemia. Anesthetic gases are combined with oxygen (O2) to provide anesthesia during surgery. It is important for RTs to be familiar with all aspects of gases used in the clinical setting, especially the chemical symbols, physical characteristics, ability to support life, and fire risk. In regard to fire risk, medical compressed gases are classified as either nonflammable (do not burn), nonflammable but supportive of combustion (also termed oxidizing), or flammable (burns readily, potentially explosive).1 Of the gases listed in Table 37-1, the focus of this chapter is on the therapeutic gases. TABLE 37-1 Physical Characteristics of Medical Gases O2 is a colorless, odorless, transparent, and tasteless gas.1 It exists naturally as free molecular O2 and as a component of a host of chemical compounds. O2 constitutes almost 50% by weight of the earth’s crust and occurs in all living matter in combination with hydrogen as water. At standard temperature, pressure, and dry (STPD), O2 has a density of 1.429 g/L, being slightly heavier than air (1.29 g/L). O2 is not very soluble in water. At room temperature and 1 atm pressure, only 3.3 ml of O2 dissolves in 100 ml of water. O2 is nonflammable, but it greatly accelerates combustion. Burning speed increases with either (1) an increase in O2 percentage at a fixed total pressure or (2) an increase in total pressure of O2 at a constant gas concentration. Both O2 concentration and partial pressure influence the rate of burning.2 O2 is produced through one of several methods. Chemical methods for producing small quantities of O2 include electrolysis of water and decomposition of sodium chlorate (NaClO3). Most large quantities of medical O2 are produced by fractional distillation of atmospheric air.1 Small quantities of concentrated O2 are produced by physical separation of O2 from air. The resulting mixture of liquid O2 and nitrogen (N, N2) is heated slowly in a distillation tower. N2, with its boiling point of 195.8° C (320.5° F), escapes first, followed by the trace gases of argon, krypton, and xenon. The remaining liquid O2 is transferred to specially insulated cryogenic (low-temperature) storage cylinders. An alternative procedure is to convert O2 directly to gas for storage in high-pressure metal cylinders. These methods produce O2 that is approximately 99.5% pure. The remaining 0.5% is mostly N2 and trace argon. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) standards require an O2 purity of at least 99.0%.3 Two methods are used to separate O2 from air.4 The first method entails use of molecular “sieves” composed of inorganic sodium aluminum silicate pellets. These pellets absorb N2, “trace” gases, and water vapor from the air, providing a concentrated mixture of more than 90% O2 for patient use. The second method entails use of a vacuum to pull ambient air through a semipermeable plastic membrane. The membrane allows O2 and water vapor to pass through at a faster rate than N2 from ambient air. This system can produce an O2 mixture of approximately 40%. These devices, called oxygen concentrators, are used primarily for supplying low-flow O2 in the home care setting. For this reason, details about the principles of operation and appropriate use are discussed in Chapter 51. Atmospheric air is a colorless, odorless, naturally occurring gas mixture that consists of 20.95% O2, 78.1% N2, and approximately 1% “trace” gases, mainly argon. At STPD, the density of air is 1.29 g/L, which is used as the standard for measuring specific gravity of other gases. O2 and N2 can be mixed to produce a gas with an O2 concentration equivalent to that of air. Medical-grade air usually is produced by filtering and compressing atmospheric air.1,5 Figure 37-1 shows a typical large medical air compressor system. In these systems, an electrical motor is used to power a piston in a compression cylinder. On its downstroke, the piston draws air through a filter system with an inlet valve. On its upstroke, the piston compresses the air in the cylinder (closing the inlet valve) and delivers it through an outlet valve to a reservoir tank. Air from the reservoir tank is reduced to the desired working pressure by a pressure-reducing valve before being delivered to the piping system. For medical gas use, air must be dry and free of oil or particulate contamination.5 The most common method used for drying air is cooling to produce condensation. For avoidance of oil or particulate contamination, medical air compressors have air inlet filters and polytetrafluoroethylene (Teflon) piston rings as opposed to oil lubrication. Large medical air compressors must provide high flow (at least 100 L/min) at the standard working pressure of 50 pounds per square inch gauge (psig) for all equipment in use. Smaller compressors (Figure 37-2) are available for bedside or home use. These compressors have a diaphragm or turbine that compresses the air and generally do not have a reservoir. This design limits the pressure and flow capabilities of these devices. For this reason, small compressors must never be used to power equipment that needs unrestricted flow at 50 psig, such as pneumatically powered ventilators (see Chapter 42). However, small diaphragm or turbine compressors are ideal for powering devices such as small-volume medication nebulizers (see Chapter 36). At STPD, CO2 is a colorless and odorless gas with a specific gravity of 1.52 (approximately 1.5 times heavier than air).1 CO2 does not support combustion or maintain animal life. For medical use, CO2 usually is produced by heating limestone in contact with water. The gas is recovered from this process and liquefied by compression and cooling. The FDA purity standard for CO2 is 99%.3 Mixtures of O2 and 5% to 10% CO2 are occasionally used for therapeutic purposes as noted in Chapter 38. Therapeutic uses include the management of singultus (hiccups), prevention of the complete washout of CO2 during cardiopulmonary bypass, and regulation of pulmonary vascular pressures in some congenital heart disorders. However, CO2 mixtures are more commonly used for the calibration of blood gas analyzers (see Chapter 18) and for diagnostic purposes in the clinical laboratory. Helium (He) is second only to hydrogen as the lightest of all gases; it has a density at STPD of 0.1785 g/L. He is odorless, tasteless, nonflammable, and chemically and physiologically inert. It is a good conductor of heat, sound, and electricity but is poorly soluble in water. Although He is present in small quantities in the atmosphere, it is commercially produced from natural gas through liquefaction to purity standards of at least 99%.3 He cannot support life, so breathing 100% He would cause suffocation and death. For therapeutic use, He must always be mixed with at least 20% O2. Heliox (a gas mixture of O2 and He) may be used clinically to manage severe cases of airway obstruction. Its low density decreases the work of breathing by making gas flow more laminar. He is discussed in more detail in Chapter 38. Nitric oxide (NO) is a colorless, nonflammable, toxic gas that supports combustion. It is produced by oxidation of ammonia at high temperatures in the presence of a catalyst. In combination with air, NO forms brown fumes of nitrogen dioxide (NO2). Together, NO and NO2 are strong respiratory irritants that can cause chemical pneumonitis and a fatal form of pulmonary edema. Exposure to high concentrations of NO alone can cause methemoglobinemia (see Chapter 11). High levels of methemoglobin can cause tissue hypoxia. As discussed in Chapter 38, NO is approved by the FDA for use in the treatment of term and near-term infants for hypoxic respiratory failure. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has published a policy statement recommending the use of NO in the care of term and near-term infants when mechanical ventilation is failing because of hypoxic respiratory failure. The AAP suggests that NO be used before extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.6 A systemic review from the Cochrane database supports the recommendation that inhaled NO at 20 ppm may be beneficial in term and near-term infants who do not have a diaphragmatic hernia (see Chapter 31).7 The use of inhaled NO in the treatment of premature neonates with hypoxic respiratory failure does not improve outcomes and may increase the risk of intracranial hemorrhage.8 Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a colorless gas with a slightly sweet odor and taste that is used clinically as an anesthetic agent. Similar to O2, N2O can support combustion. However, N2O cannot support life and causes death if inhaled in pure form. For this reason, inhaled N2O must always be mixed with at least 20% O2. N2O is produced by thermal decomposition of ammonium nitrate.1 Long-term human exposure to N2O has been associated with a form of neuropathy. In addition, epidemiologic studies have linked chronic N2O exposure with an increased risk of fetal disorders and spontaneous abortion.1 On the basis of this knowledge, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (a division of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration) has set an upper exposure limit for hospital operating rooms of 25 ppm N2O.1 The containers used to store and ship compressed or liquid medical gases are high-pressure cylinders. The design, manufacture, transport, and use of these cylinders are carefully controlled by both industrial standards and federal regulations. Gas cylinders are made of seamless steel and are classified by the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) according to their fabrication method. DOT type 3A cylinders are made from carbon steel, and DOT type 3AA containers are manufactured with a steel alloy tempered for higher strength.1 Medical gas cylinders are marked with metal stamping on the shoulders that supplies specific information (Figure 37-3).1,9 Although the exact location and order of these markings vary, the practitioner should be able to identify several key items of information. Safety tests are conducted on each cylinder every 5 or 10 years, as specified in DOT regulations.1,9 During these tests, cylinders are pressurized to five thirds of their service pressure. While the cylinder is under pressure, technicians measure cylinder leakage, expansion, and wall stress. The notation EE followed by a number indicates the elastic expansion of the cylinder in cubic centimeters under the test conditions. An asterisk (*) next to the test date indicates DOT approval for 10-year testing. A plus sign (+) means the cylinder is approved for filling to 10% greater than its service pressure. An approved cylinder with a service pressure of 2015 psi can be filled to approximately 2200 psi. After hydrostatic testing, cylinders are subjected to internal inspection and cleaning. In addition to these permanent marks, all cylinders are color-coded and labeled for identification of their contents.1,10 Table 37-2 lists the color codes for medical gases as adopted by the Bureau of Standards of the U.S. Department of Commerce.11 For comparison, the color codes adopted by the Canadian Standards Association also are included. Color codes are not standardized internationally. For this reason, cylinder color should be used only as a guide. As with any drug agent, the cylinder contents always must be identified through careful inspection of the label. To be absolutely sure about the O2 concentration provided by a cylinder, the user must analyze the gas before administering it (see Chapter 18).12 TABLE 37-2 Color Codes for Medical Gas Cylinders *Vacuum systems historically are identified as white in the United States and yellow in Canada. For this reason, the CGA recommends that white not be used for any cylinders in the United States and that yellow not be used in Canada. Letter designations are used for different sizes of cylinders (Figure 37-4). Sizes E through AA are referred to as “small cylinders” and are used most often for transporting patients and anesthetic gases. These small cylinders are easily identified because of their unique valves and connecting mechanisms. Small cylinders have a post valve and yoke connector. Large cylinders (F through H and K) have a threaded valve outlet (Figure 37-5) (discussed later). Gases with critical temperatures greater than room temperature can be stored as liquids at room temperature (see Chapter 6). These gases include CO2 and N2O. Rather than being filled to filling pressure, cylinders of these gases are filled according to a specified filling density. The filling density is the ratio between the weight of liquid gas put into the cylinder and the weight of water the cylinder could contain if full. The filling density for CO2 is 68%. This system allows the manufacturer to fill a cylinder with liquid CO2 up to 68% of the weight of water that a full cylinder could hold. The filling density of N2O is 55%. Figure 37-6 compares the behavior of compressed gas and liquid gas cylinders during use. The vapor pressure of liquid gas cylinders varies with the temperature of the contents. The pressure in an N2O cylinder at 21.1° C (70° F) is 745 psig; at 15.6° C (60° F), the pressure decreases to 660 psig. As the temperature increases toward the critical point, more liquid vaporizes, and the cylinder pressure increases. If a cylinder of N2O warms to 36.4° C (97.5° F) (its critical temperature), all the contents convert to gas. Only at this temperature and higher does the cylinder gauge pressure accurately reflect cylinder contents.

Storage and Delivery of Medical Gases

Describe how medical gases and gas mixtures are produced.

Describe how medical gases and gas mixtures are produced.

Discuss the clinical applications for medical gases and gas mixtures.

Discuss the clinical applications for medical gases and gas mixtures.

Distinguish between gaseous and liquid storage methods.

Distinguish between gaseous and liquid storage methods.

Calculate the duration of remaining contents of a compressed oxygen cylinder.

Calculate the duration of remaining contents of a compressed oxygen cylinder.

Calculate the duration of remaining contents of a liquid oxygen cylinder.

Calculate the duration of remaining contents of a liquid oxygen cylinder.

Describe how to store, transport, and use compressed gas cylinders properly.

Describe how to store, transport, and use compressed gas cylinders properly.

Distinguish between gas supply systems.

Distinguish between gas supply systems.

Describe what to do if a bulk oxygen supply system fails.

Describe what to do if a bulk oxygen supply system fails.

Differentiate among safety systems that apply to various equipment connections.

Differentiate among safety systems that apply to various equipment connections.

Select the appropriate devices to regulate gas pressure or control flow in various clinical settings.

Select the appropriate devices to regulate gas pressure or control flow in various clinical settings.

Describe how to assemble, check for proper function, and identify malfunctions in gas delivery equipment.

Describe how to assemble, check for proper function, and identify malfunctions in gas delivery equipment.

Identify and correct common malfunctions of gas delivery equipment.

Identify and correct common malfunctions of gas delivery equipment.

Gas

Chemical Symbol

Color

Taste

Odor

Can Support Life

Flammability

Laboratory Gases

Nitrogen

N

Colorless

Tasteless

Odorless

No

Nonflammable

Helium

He

Colorless

Tasteless

Odorless

No

Nonflammable

Carbon dioxide

CO2

Colorless

Slightly acidic

Odorless

No

Nonflammable

Therapeutic Gases

Air

AIR

Colorless

Tasteless

Odorless

Yes

Supports combustion

Oxygen

O2

Colorless

Tasteless

Odorless

Yes

Supports combustion

Helium/oxygen (heliox)

He/O2

Colorless

Tasteless

Odorless

Yes

Supports combustion

Carbon dioxide/oxygen

CO2/O2

Colorless

Slightly acidic

Odorless

No

Supports combustion

Nitric oxide

NO

Colorless

Tasteless

Metallic

No

Supports combustion

Anesthetic Gas

Nitrous oxide

N2O

Colorless

Slightly sweet

Slightly sweet

No

Supports combustion

Characteristics of Medical Gases

Oxygen

Characteristics

Production

Fractional Distillation

Physical Separation

Air

Carbon Dioxide

Helium

Nitric Oxide

Nitrous Oxide

Storage of Medical Gases

Gas Cylinders

Markings and Identification

Gas

United States

Canada

O2

Green

White*

CO2

Gray

Gray

N2O

Blue

Blue

Cyclopropane

Orange

Orange

He

Brown

Brown

C2H4

Red

Red

CO2-O2

Gray/green

Gray/white

He-O2

Brown/green

Brown/white

N2

Black

Black

Air

Yellow*

Black/white

N2-O2

Black/green

Pink

Cylinder Sizes and Contents

Filling (Charging) Cylinders

Liquefied Gases

Measuring Cylinder Contents

Liquid Gas Cylinders

Storage and Delivery of Medical Gases