Chapter 20 Stent Insertion for Extrinsic Tracheal Obstruction Caused by Thyroid Carcinoma

Case Description

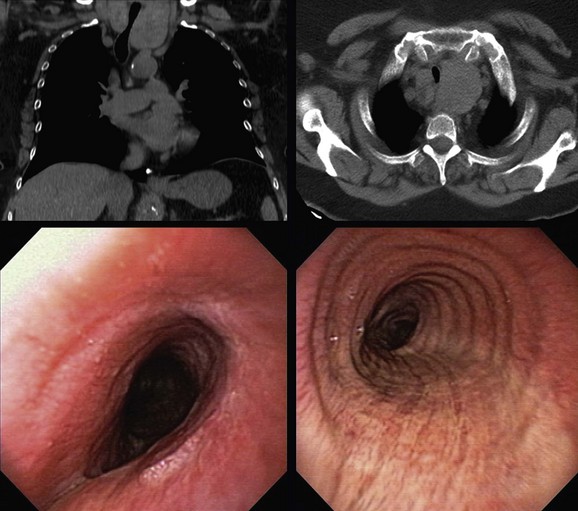

This patient was a 67-year-old obese (BMI, 37 kg/m2) African American female with a 25–pack-year history of smoking who developed progressive dyspnea on exertion, cough, and hoarseness. She had a history of COPD (FEV1 45% predicted) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) treated with CPAP of 10 cm H2O. Physical examination was remarkable for biphasic stridor, heard best during forced inspiratory and expiratory maneuvers. Computed tomography scanning showed the intrathoracic extension of a thyroid mass, narrowing the trachea (Figure 20-1). Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration of the thyroid mass revealed papillary thyroid carcinoma. The patient was referred for evaluation and management of her tracheal obstruction before performance of a complete thyroidectomy. Flexible bronchoscopy performed under moderate sedation with the patient in a semi-upright position showed redundant pharyngeal and laryngeal tissues; the arytenoid cartilages were edematous and were collapsing over the vocal folds during inspiration (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video V.20.1![]() ). Tracheal narrowing was due to pure extrinsic compression without mucosal infiltration or exophytic endoluminal abnormalities. The stenotic segment was located 3.5 cm below the cords and extended for 3 cm. The degree of narrowing was 60% during inspiration and 70% during tidal expiration as compared with the normal airway lumen (see Figure 20-1).

). Tracheal narrowing was due to pure extrinsic compression without mucosal infiltration or exophytic endoluminal abnormalities. The stenotic segment was located 3.5 cm below the cords and extended for 3 cm. The degree of narrowing was 60% during inspiration and 70% during tidal expiration as compared with the normal airway lumen (see Figure 20-1).

Discussion Points

1. List four indications for airway stent insertion in this patient.

2. List and justify four anesthesia considerations of rigid bronchoscopy in view of this patient’s medical history, physical examination, and tracheal obstruction.

3. Describe and justify one indication for prolonged indwelling airway stent placement if this patient undergoes successful thyroidectomy.

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

Thyroid disease with airway obstruction has been described in patients with thyroid carcinoma and in those with benign goiters.1,2 Mechanisms of airway obstruction include extrinsic compression (e.g., benign intrathoracic or substernal goiter), airway invasion by tumor (e.g., thyroid cancer), tracheomalacia (e.g., after thyroidectomy or long-term compression from goiter), vocal cord paralysis (e.g., recurrent nerve paralysis due to tumor or after thyroidectomy), and a combination of these.3 The most frequent cause of airway obstruction in the presence of thyroid disease is substernal (benign or malignant) goiter compressing the trachea with or without associated tracheomalacia.4 In the setting of thyroid carcinoma, symptoms associated with mucosal invasion such as hemoptysis (seen in 11% to 39% of patients) and airway obstruction causing dyspnea (seen in 5% to 89% of patients) underestimate the depth of airway invasion because they are usually present in patients with a most advanced degree of invasion (i.e., when the tumor is already intraluminal). Even deep tumor invasion into the tracheal wall often is not identified before surgery unless fixation of the gland is obvious on physical examination.5 In this regard, physical examination during initial evaluation of patients with thyroid carcinoma may not suffice to identify a thyroid mass as a cause of respiratory problems. In fact, in one small series of five patients with acute airway obstruction, goiters were palpable in three patients, whereas the other two goiters were diagnosed by emergency computed tomography (CT) of the thorax.6

Malignant airway obstruction caused by a primary tumor or by recurrent disease is the cause of death in one half of all patients with thyroid carcinoma.7 In general, well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma is considered an indolent disease with an 80% to 95% 10 year survival rate.8 In about 5.7% to 7% of cases of well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma, the tumor invades adjacent laryngotracheal structures,9 and changes in clinical status may occur only when it reaches the mucosa. It is important that patients with malignant thyroid disease be evaluated by CT imaging of the neck and chest and by flexible bronchoscopy to assess the extent and the severity of the narrowing, and to determine whether intraluminal tumor or extrinsic compression is the main cause of obstruction, especially if patients are being considered for complete thyroidectomy. Some patients, such as those for whom radical surgery for laryngotracheal invasion is not feasible owing to poor physical condition or those who are symptomatic from airway narrowing, may not be candidates for curative surgery but may be suitable for palliative bronchoscopic interventions.

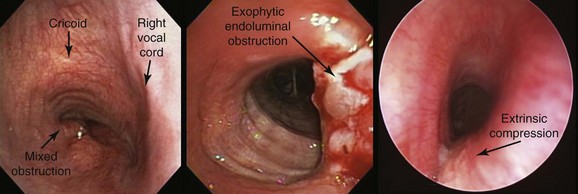

In our patient, bronchoscopic inspection was conducted to evaluate for possible vocal cord paralysis, airway tumor invasion, and the mechanism of obstruction: exophytic endoluminal versus pure extrinsic versus mixed extrinsic and intraluminal (Figure 20-2).10 In fact, one study found unilateral vocal cord paralysis in 83% of patients with thyroid carcinoma.11 During bronchoscopy, if the airway mucosa is abnormal, biopsy of the intraluminal tumor can and should be performed because positive results predict a worse prognosis.12 Indeed, the depth of airway invasion appears to predict outcome, with shorter survival reported in patients with endoluminal tumor.13 Other bronchoscopic findings in patients with thyroid disease–induced airway involvement include erythema and edema, neovascular formation, and frank mucosal invasion.12 Tracheal invasion should be clearly documented by the bronchoscopist; this is of particular interest to surgeons because it is a marker for more aggressive tumors and defines a patient population at greater risk for death.5,7 Results from one study of 18 cases of thyroid cancer infiltrating the trachea showed poor tumor differentiation in 50% of papillary and follicular carcinomas compared with 11.4% when airways were not invaded.14 Among 292 patients with well-differentiated papillary carcinoma, the most commonly encountered histology, authors identified laryngotracheal invasion in 124 patients (41%) as a significant independent predictor of death.15 An additional study found that laryngotracheal or esophageal invasion was an important negative prognostic factor, indicating that tracheal invasion lowers long-term survival.16

Usually identified at the time of operation, extraluminal airway invasion demands a decision regarding the extent of resection. The proportion of patients with thyroid cancer involving the larynx and the trachea depends not only on histology but also on the definition of invasion. Invasion into the tracheal wall or the larynx in the form of external adherence was noted in surgical studies to vary from 3.6% to 22.9% of all patients undergoing thyroidectomy.*5 The most advanced stage of invasion constitutes intraluminal tumor, which is more rare and is detected on bronchoscopy in only 0.5% to 1.5% of patients presenting for resection. Radiologic criteria such as compression or displacement by tumor, which occurred in up to 35%, may overestimate invasion. Thus bronchoscopy remains essential in determining endoluminal involvement, surgical strategy, and outcome.5 In our patient, who had no evidence of endoluminal invasion, bronchoscopy was necessary to determine the site, severity, and length of the tracheal obstruction to allow selection of a tracheal stent of appropriate length and size to relieve her symptoms.

Patient Preferences and Expectations

The patient understood her diagnosis. She and her daughter had already talked about it in detail with the treating surgeon. At the time of our encounter, the patient did not have an advance directive and was reluctant to initiate one. In this regard, it is possible that among African Americans, nonacceptance of advance directives may be part of a different set of values regarding quality of life and trust in health care professionals.† Do not resuscitate (DNR) orders may be viewed as a way of limiting health care expenditures or cutting costs by stopping care prematurely.17 Furthermore, the reluctance of African Americans to address end-of-life care in a formal fashion may originate from a history of health care discrimination. Evidence indicates that nonwhites, even after controls for income, insurance status, and age are applied, are less likely to receive a range of common medical interventions such as analgesics for acute pain, cardiac catheterization, and even immunizations.17 Overall, African American patients are about one half as likely to accept DNR status and are more likely than whites to later change DNR orders to more aggressive levels of care.18

Procedural Strategies

Indications

Clinically manifest airway obstruction due to thyroid enlargement is considered to be an absolute indication for surgical intervention. In general, treatment of differentiated primary thyroid cancer consists of total thyroidectomy followed by adjuvant radioiodine treatment and suppressive thyroxine therapy. Indications for bronchoscopic treatment in benign and malignant thyroid disorders causing airway obstruction include refusal of surgery, medical or surgical inoperability, tracheomalacia, and acute severe respiratory insufficiency with imminent respiratory failure. An indication specific to malignant disease is recurrence after previous surgery.3 In one series, among patients requiring bronchoscopic treatment for malignant disease, 10 patients (77%) had purely extrinsic compression of the trachea requiring stent insertion, 1 with associated bilateral vocal cord paralysis, and 3 patients (23%) showed mixed obstruction with extrinsic tracheal compression associated with exophytic endoluminal disease (see Figure 20-2).3 Indications for interventional bronchoscopy in our patient included stridor, dyspnea, and potential avoidance of tracheomalacia post thyroidectomy. Tracheal stent insertion could provide our patient with symptomatic relief of her respiratory difficulties while subsequently allowing the surgical team to perform a potentially curative resection. In one study, for example, airway patency was maintained with covered retrievable self-expandable nitinol stents until surgery was performed. Stents were successfully removed within 3 weeks after surgery.19

In patients who are not operable, however, stent insertion, by improving functional status, allows the medical team to proceed with palliative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. Tracheal stents should not be placed prophylactically in these patients just because the airway is extrinsically compressed or invaded by tumor. Airway involvement should cause symptoms that warrant stent insertion. This is especially true in patients with thyroid cancer because most tumors (≈80%) are located in the larynx and at the level of the cricoid cartilage—a region where stents are at high risk for migration and may not be well tolerated owing to their close proximity to the vocal cords.12 Even in mixed forms of obstruction, ablation of the intraluminal lesion is the first-line procedure (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video V.20.2![]() ), but stent insertion becomes necessary when symptomatic airway stenosis results from increased extrinsic compression, or when repeated removal of an intraluminal lesion at short intervals is due to a fast-growing tumor. In one study, this approach was shown to succeed in maintaining airway patency, and the cause of death in two thirds of patients was not airway obstruction but progression of preexisting lung metastases or carcinomatous pleuritis.12

), but stent insertion becomes necessary when symptomatic airway stenosis results from increased extrinsic compression, or when repeated removal of an intraluminal lesion at short intervals is due to a fast-growing tumor. In one study, this approach was shown to succeed in maintaining airway patency, and the cause of death in two thirds of patients was not airway obstruction but progression of preexisting lung metastases or carcinomatous pleuritis.12

Expected Results

In multiple reports, researchers have revealed their experience with tracheal stent placement for palliation in patients with thyroid disease such as benign intrathoracic or substernal goiter, thyroid cancer, thyroid lymphoma, and tracheomalacia after thyroidectomy. For this purpose, they have used silicone stents, covered or uncovered metallic stents, T-tubes, or tracheostomy tubes.3,11 In one series of 16 patients with malignant thyroid disease, neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd : YAG) laser treatment (n = 3) and stent insertion* (n = 13) resulted in restoration of airway patency and symptomatic improvement in 92% of patients (see video on ExpertConsult.com) (Video V.20.3![]() ). Data revealed 15% short-term† and 8% long-term complications‡ and a median survival time (MST) of 17 months.3 Shorter survival times of only 4 months were reported, however, by other investigators.20 In a large retrospective study of 35 patients with advanced thyroid cancer requiring stent insertion for managing airway obstruction, the authors compared studded silicone stents (Novatech, Aubagne, France) and T-tubes (Koken, Tokyo, Japan) versus self-expandable metallic stents—covered and uncovered Ultraflex (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass) and Spiral Z (Medico’s Hirata, Tokyo, Japan).11 All patients reported immediate symptomatic relief objectively documented by improvements in both Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and the Hugh-Jones dyspnea scale. MST was 8 months. One-year survival was 40%, but death was due to progression of disease at sites other than the airway.11 In this series, almost all stent-related complications requiring further intervention occurred in patients who had a studded silicone stent or a T-tube inserted. These included stent migration, retained secretions, granulation tissue formation, and tumor overgrowth. Critical complications of stent insertion included supraglottic stenosis (5 cases, 14% of stent implantations) and migration within 1 week of insertion (4 cases, 11% of stent implantations). These were associated with studded silicone stents in the proximity of the cricoid cartilage, indicating that migration occurred in as many as 40% of all studded silicone stent placements.11

). Data revealed 15% short-term† and 8% long-term complications‡ and a median survival time (MST) of 17 months.3 Shorter survival times of only 4 months were reported, however, by other investigators.20 In a large retrospective study of 35 patients with advanced thyroid cancer requiring stent insertion for managing airway obstruction, the authors compared studded silicone stents (Novatech, Aubagne, France) and T-tubes (Koken, Tokyo, Japan) versus self-expandable metallic stents—covered and uncovered Ultraflex (Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass) and Spiral Z (Medico’s Hirata, Tokyo, Japan).11 All patients reported immediate symptomatic relief objectively documented by improvements in both Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status and the Hugh-Jones dyspnea scale. MST was 8 months. One-year survival was 40%, but death was due to progression of disease at sites other than the airway.11 In this series, almost all stent-related complications requiring further intervention occurred in patients who had a studded silicone stent or a T-tube inserted. These included stent migration, retained secretions, granulation tissue formation, and tumor overgrowth. Critical complications of stent insertion included supraglottic stenosis (5 cases, 14% of stent implantations) and migration within 1 week of insertion (4 cases, 11% of stent implantations). These were associated with studded silicone stents in the proximity of the cricoid cartilage, indicating that migration occurred in as many as 40% of all studded silicone stent placements.11

Team Experience

For inoperable patients requiring bronchoscopic treatments, procedures are usually performed with the patient under general anesthesia and using rigid bronchoscopy.3,11 Therefore referral to a center experienced in this procedure is warranted. For operable patients, the surgeon who is unfamiliar with techniques of open tracheal resection has several options when encountering tracheal invasion, including operative exploration without thyroidectomy, or leaving complete, combined resection to the surgeon trained in thyroid and airway procedures. Alternatively, combined resection may be performed by a multidisciplinary team of thyroid and tracheal surgeons. If thyroidectomy has been completed with a shave resection, tracheal or laryngotracheal resection may then be performed after referral to a surgeon experienced in airway surgery.5

Therapeutic Alternatives

Endoscopic tumor ablation by debulking with an Nd : YAG laser has been performed for patients with endoluminal tumor involvement in whom radical operations are contraindicated. In one study, 22 consecutive patients underwent endoscopic tumor ablation* for well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma. During a follow-up period of up to 125 months, 6 of 22 patients died (median survival, 50 months), mainly of lung metastases, but all had a patent airway at the time of death. The authors noted that post intervention extraluminal lesion growth is indolent, and because relapse of the intraluminal lesion is the main cause of symptoms, local control could be obtained by repeat ablation of the mucosal lesion.12

Tracheostomy is the traditional method used for primary treatment of acute airway obstruction due to malignant invasion and compression of the trachea from thyroid carcinoma. However, insertion of tracheal stents may obviate the need for tracheostomy.11 Indeed, emergent stent insertion in 10 patients with a severe, mixed type of airway obstruction caused by various malignancies, including papillary thyroid carcinoma, resulted in a median survival time of 8 months.21 Patients with repeated local recurrence over a long period from the time of initial treatment often are unable to undergo radical surgery, in which case tracheotomy could be performed to establish a patent airway. Tracheostomy may be technically difficult, however, in the case of a large, bulky thyroid mass,22 in which case a tracheal stent is often a feasible alternative.

Surgical airway resection when performed immediately after detection of airway invasion at the time of thyroidectomy is associated with longer disease-free survival compared with later resection (after a mean period of 67 months, at recurrence).23 In our patient, no airway mucosal invasion was evident on bronchoscopy; however, if detected at the time of surgery, airway resection could become necessary. In general, strategies for surgical resection of the airway for laryngotracheal invasion are considered in five different clinical settings5: (1) when the thyroid gland adheres to the airway at the time of initial thyroidectomy; (2) in cases referred after incomplete tangential excision* of tumor; (3) when invasion with airway obstruction is detected before the time of surgical therapy; (4) in cases of local recurrence with airway obstruction late after thyroidectomy; and (5) in some cases of airway obstruction in the presence of distant metastatic disease.† Several surgical alternatives have been described and include tangential excision of tumor, tracheal or laryngotracheal sleeve resection,‡ and laryngectomy with cervical exenteration,§ all of which usually are considered salvage resections for patients with extensive invasive disease or locoregional recurrent disease following previous resection or radiation.5,24

Self-expandable metallic stents are a reasonable alternative to silicone stent insertion in inoperable patients with malignant thyroid tumor and airway obstruction.11 Placement of covered retrievable self-expandable nitinol stents was safe and effective in patients with airway obstruction caused by benign or malignant thyroid disease, and in some patients served as an effective bridge to surgery.19 For patients with thyroid carcinoma, one study showed that the uncovered Ultraflex stent was associated with fewer complications (supraglottic obstruction and migration) than were observed with silicone stents.11

Radioactive iodine (RAI) therapy: This is usually indicated alone for metastatic or locally advanced disease when surgical options are exhausted. Postoperatively, this adjuvant therapy for residual disease in the tracheal wall may have limited effectiveness because tumors invading the airway are often less differentiated, may have less RAI uptake, and may be resistant to therapy. However, postoperative adjuvant RAI is commonly administered after surgical resection.5

External beam radiation therapy (EBRT): Adjuvant or palliative radiation is proposed to improve local control for patients with advanced cancer after incomplete resection. EBRT may potentially improve recurrence rates25 in patients with resected locally advanced disease.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree