Chapter 10 Bronchoscopic Treatment of Wegener’s Granulomatosis–Related Subglottic Stenosis

Case Description

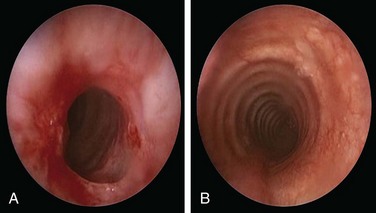

A 49-year-old woman with a 20 year history of Wegener’s granulomatosis (WG) now presents with cough and limited exercise capacity. Disease had been limited to her sinuses and had been treated in years past with prednisone and cyclophosphamide (CYC). CYC was switched to methotrexate owing to hematuria. Her last relapse occurred 18 months earlier. She was active and routinely swam 10 laps in her pool until 2 months ago, when she developed a dry cough and shortness of breath. Her primary care physician ordered a two-dimensional echocardiogram, which was normal. Physical examination was unremarkable except for her cushingoid face. Chest radiograph, complete blood count, urine analysis, and liver function test results were normal. Diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy revealed a circumferential subglottic stenosis (SGS) extending 0.5 cm and starting 1.5 cm below the vocal cords. The cross-sectional area at the level of the stricture was reduced by 53% when compared with the normal tracheal lumen distal to the stricture, as measured by morphometric analysis of the bronchoscopic images (Figure 10-1).

Discussion Points

1. Describe five central airway abnormalities seen in Wegener’s granulomatosis.

2. Discuss the role of antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) in monitoring this patient’s disease activity.

3. Describe two adjuvant treatments to laser-assisted dilation of WG-related stenosis.

4. Discuss the prognosis of patients with WG and subglottic stenosis.

Case Resolution

Initial Evaluations

Physical Examination, Complementary Tests, and Functional Status Assessment

In our patient, the diagnosis of subglottic stenosis occurred in the absence of other features of active disease. Tracheobronchial manifestations of WG may take place after remission has been achieved with appropriate immunosuppressive therapy, and airway disease may proceed to airway scarring and stenosis.1 In the absence of persistent active inflammation, however, the development of SGS does not necessarily indicate failure of immunosuppressive therapy. As in our patient, published and anecdotal evidence suggests that when airway obstruction is caused by fibrotic scarring rather than by active inflammation, strictures develop independently of other features of WG and are unresponsive to systemic immunosuppressive therapy.2 SGS, seen in approximately 8.5% to 23% of patients, is considered the most common central airway manifestation of WG. It may be the initial presenting feature in 1% to 6% of patients.3 Isolated SGS is observed in approximately 50% of patients with strictures; in the other half, strictures occur while patients are receiving systemic immunosuppressive therapy for disease activity involving other sites.4

This patient had no stridor on neck auscultation. This finding is consistent with the bronchoscopic classification of moderate airway narrowing based on a stenotic index of 53%. Indeed, stridor is usually a sign of severe laryngeal or tracheal obstruction, signaling more than 70% airway lumen narrowing.5–7 Anatomically fixed obstruction of moderate degree such as that seen in our patient usually causes symptoms with exertion but not at rest.

The absence of ANCA in our patient was not unexpected. In fact, the presence or absence of ANCA neither confirms nor excludes a diagnosis of systemic vasculitis, and both negative and positive predictive values will be strongly influenced by clinical presentation. Most patients with generalized WG have glomerulonephritis and are ANCA positive (90%), whereas those without renal involvement have a lower incidence of ANCA (70%). Among patients with limited forms of the disease, such as those without significant renal involvement and in whom upper respiratory tract symptoms predominate, only 60% are ANCA positive.8

Comorbidities

Lack of cardiac involvement by two-dimensional echocardiography (2D echo) was reassuring because WG disease relapse is often associated with heart involvement, less intensive initial treatment in terms of lower CYC doses, and shorter length of time on prednisone >20 mg/day.9 No evidence of renal or hepatic dysfunction was found; if surgical or bronchoscopic interventions were to be provided under general anesthesia, such dysfunction could adversely affect perioperative fluid management, increase risks for bleeding, and cause postoperative changes in neurologic status.

Support System

Our patient was married and had a good social support system. As with other chronic conditions, considerable evidence suggests that vasculitis negatively affects patients’ health-related quality of life (HRQL),10 which usually includes general health, physical functioning, emotional role limitations, physical role limitations, social functioning, mental health, and energy/vitality. Contrary to cancer, which is often considered a “family affair” with significant psychological and emotional impact on family members,11 results of recent studies show that spouses of patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis (AAV), including WG, scored similarly to national norms. Patients with AAV, however, scored lower than normal on all HRQL subscales with the exception of bodily pain. When age, education, race, illness duration, and disease severity were controlled, no significant sex differences in HRQL were noted for patients or spouses.12

Patient Preferences and Expectations

This patient had a very active lifestyle and had clearly expressed a desire for treatment. She was prepared to consider all available therapeutic options, including dilation, laser, surgery, and even airway stent insertion if necessary. She agreed to our request that alternatives be discussed with her husband, so they could participate together in medical decision making. Health care provider investment in patient-centered conversations with family members is usually justified because management of chronic illness is a dyadic process that often involves spouses.13

Procedural Strategies

Indications

Symptomatic WG-related subglottic stenosis is often part of the spectrum of a multisystem inflammatory process that warrants administration of immunosuppressive agents. Some patients, however, develop or continue to have symptoms of airway obstruction after clinical remission induced by standard therapeutic regimens. Although airway manipulation during periods of active WG should be minimized, other treatment modalities may be warranted14 after disease has first been controlled in collaboration with a rheumatologist. A bronchoscopic procedure or open laryngotracheoplasty may be offered to improve dyspnea and restore satisfactory airway lumen patency by mechanical dilation with or without laser.

In patients with tracheal obstruction, dyspnea depends on the degree of airway narrowing, as well as on flow velocity. Airway pressures increase dramatically at rest when well over 70% of the tracheal lumen is obliterated. Our patient’s active lifestyle caused high flow velocity through her stenotic airway. This further increased the pressure drop through the stricture, increasing the work of breathing.15 Improving airway patency to a lesser (mild) degree of narrowing (<50%) would allow our patient to improve exercise capacity and shortness of breath. In one physiology study, the effect of the normal glottis on airway pressure drop is, in fact, of the same order as that of 50% airway narrowing.16 Thus when airway narrowing is treated, symptoms and exercise tolerance may be dramatically improved by small changes in airway caliber, and perfect normalization of airway lumen patency may not be necessary.

Expected Results

In patients with subglottic strictures, the therapeutic success of rigid bronchoscopic dilation is variable. In one study (follow-up after the first dilation of 25.4 ± 14.1 months), two of nine patients never recurred after the initial dilation, and seven required more than one dilation, with one patient requiring permanent tracheostomy.17 In another study, three patients required repeated treatment using neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Nd:YAG) or carbon dioxide (CO2) laser–guided resection to control airway narrowing.14

Team Experience

Experience and expediency might result in reduced complications, a greater chance to restore airway patency, and earlier discharge from the hospital, although studies are needed to support this hypothesis. Prospective and ongoing data analysis for bronchoscopic procedures, both feasible and ongoing, might answer these questions in the future.18

Therapeutic Alternatives for Restoring Airway Patency

Therapeutic alternatives include systemic, bronchoscopic, and open surgical therapies. If disease severity is judged to be life threatening or to be putting an affected organ at risk for irreversible damage, such as airway or renal disease, glucocorticoids in combination with CYC remain the treatment of choice. In less severe cases, methotrexate is the preferred alternative to CYC. Regardless of the severity of other organ manifestations, severe tracheobronchial disease should initially be treated with a combination of oral glucocorticoids and CYC. For patients with documented tracheobronchial disease, some experts use high-dose inhaled glucocorticoids, such as fluticasone 440 to 880 mg twice daily, which is usually initiated when oral glucocorticoids have been tapered to daily doses less than 30 mg.19 Because our patient had failed two immunosuppressive drugs (glucocorticoids and methotrexate) and was intolerant to CYC, one might consider her as having refractory disease. A monoclonal anti-CD20 antibody, rituximab, was shown to be successful in inducing remission in patients with refractory but limited WG manifestations, including chronic sinusitis, pulmonary nodules, orbital pseudotumor, and subglottic stenosis.20 Others, however, report systemic therapy–induced cures at all disease locations except the subglottis.21

Because isolated airway lesions secondary to scarring may improve only after interventional procedures, the decision to use concomitant immunosuppressive medications depends on clinical and laboratory features that may suggest active disease.3 Overall, only 20% to 26% of subglottic strictures caused by Wegener’s granulomatosis respond to glucocorticoids alone or in combination with another immunosuppressant. The remaining 74% to 80% of patients usually require interventional therapies to improve symptoms. In our patient, without clinical or laboratory evidence of other organ involvement, the isolated SGS was considered a manifestation of the scarring process, and she was offered an interventional procedure.

• Balloon or bougie dilation (e.g., Maloney bougies, Fogarty catheter balloon) can be used to increase the airway lumen to facilitate the atraumatic passage of a rigid bronchoscope, or as a sole treatment modality. Balloon dilation can be performed by using flexible bronchoscopy with a balloon catheter threaded over a guidewire and positioned across the stenosis, or by inserting the balloon catheter through the working channel of the bronchoscope. Under direct visualization, the balloon is inflated for 30 to 120 seconds. Repeat inflation-deflation cycles are done if airway narrowing persists after the initial attempt.22

• Adjuvant therapies such as intralesional corticosteroid injection have been reported to reduce the rate of recurrence after bronchoscopic dilation of WG-related SGS. Methylprednisolone acetate is injected directly into the stenotic segment, followed by lysis of the stenotic tissue and serial dilation.4,23,24 In a series with 21 patients (no control group) followed for a mean of 40.6 months, patients who did not have scarring from previous procedures required a mean of 2.4 procedures at mean intervals of 11.6 months to maintain subglottic patency. Patients with established laryngotracheal scarring required a mean of 4.1 procedures at mean intervals of 6.8 months to maintain patency. None of the 21 patients required a new tracheostomy.24 Older studies with a larger number of patients (n = 43) also showed that this approach provides safe and effective treatment for WG-associated subglottic strictures, and that in the absence of major organ disease activity, it can be performed without concomitant administration of systemic immunosuppressive agents.4 Topical application of mitomycin C, an alkylating agent that inhibits fibroblast proliferation and extracellular matrix protein synthesis, can be performed after intralesional corticosteroid injection, dilation, or laser resection with the intent of reducing fibrosis and restenoses. Some authors, however, recommend its use only in patients with active inflammatory lesions.17 A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of patients with laryngotracheal stenosis, including 2 patients with WG, compared restenosis rates with two applications of mitomycin C (0.5 mg/mL for 5 minutes on a 1 × 1 inch cottonoid) given 3 to 4 weeks apart versus one application immediately after surgery.25 Although relapses occurred at a slower rate in the two-application group during the first 3 years, recurrence of laryngotracheal stenosis 5 years after surgery was similarly high (70%) in both groups.

• Laser resection using CO2 or Nd:YAG lasers in Wegener’s granulomatosis patients has shown conflicting results.2,14,26,27 Two studies showed good outcomes in 5 patients after repeated sessions with both lasers14 and in 12 patients with a combination of CO2 laser and dilation.27 In another study, 8 patients developed rapid restenosis after treatment with a CO2 laser.26 Favorable results have been described for avoiding laser intervention when disease is active, prompting investigators to recommend minimizing airway manipulation during periods of systemic disease activity.27

• Silicone and covered metal stent insertion have been used successfully in WG-related subglottic strictures when the glottis is not involved (diseased segment starting at least 1 cm below the vocal cords).28 Covered metal stents are associated with significant complications, especially when in the subglottic region,29 however, and probably should be avoided for histologically proven benign airway disorders.30 Silicone stents seem to provide long-lasting symptomatic relief31 but should be considered only when more conservative treatment modalities fail to restore or maintain airway patency. Stents of any type are a last resort in WG-related subglottic stenosis; some experts consider subglottic stent insertion, without first-line medical and conservative therapy, to be a simple but wrong solution for a complex problem.29

• Open surgical resection such as laryngotracheoplasty or other reconstructive techniques are alternatives for patients who fail bronchoscopic intervention. In one study, 3 of 5 patients underwent primary thyrotracheal anastomosis while disease was in clinical remission, without postoperative compromise of anastomotic integrity or wound healing despite concurrent use of prednisone and CYC.32 Extensive surgical resection is not recommended in patients with active disease because reactivation in the remaining subglottis may cause dehiscence of anastomotic sites and recurrent stenosis.33 Following surgical resection, patients may require dilations or stent placement.34 Results from an older, larger study of thoracic surgery in patients with WG showed that among 47 patients followed over 16 years, only 3 had subglottic strictures. Each was treated by dilation, not by surgical resection.35

• Tracheostomy is warranted in patients with critical airway stenosis unresponsive to medical and dilational therapies. This procedure can be lifesaving and can provide long-term relief. In one series of 27 patients with WG and subglottic strictures, 11 (41%) underwent tracheotomy. Eventual decannulation was possible in a variable percentage of patients.27

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree