14 ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction

Etiology and Pathogenesis

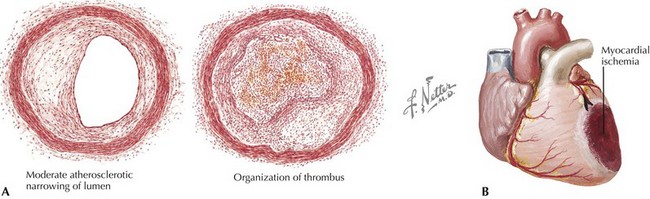

The initial event in formation of an occlusive intracoronary thrombus is rupture or ulceration of an atherosclerotic plaque. Plaque rupture results in exposure of circulating platelets to the thrombogenic contents of the plaque, such as fibrillar collagen, von Willebrand factor, vitronectin, fibrinogen, and fibronectin. Adhesion of platelets to the ulcerated plaque, with subsequent platelet activation and aggregation, leads to thrombin generation, conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin, and further activation of platelets, as well as vasoconstriction, due in part to platelet-derived vasoconstrictors. This prothrombotic milieu promotes propagation and stabilization of an active thrombus that contains platelets, fibrin, thrombin, and erythrocytes, resulting in occlusion of the infarct-related artery (Fig. 14-1A). Upon interruption of antegrade flow in an epicardial coronary artery, the zone of myocardium supplied by that vessel immediately loses its ability to perform contractile work (Fig. 14-1B). Abnormal contraction patterns develop: dyssynchrony, hypokinesis, akinesis, and dyskinesis. Myocardial dysfunction in an area of ischemia is typically complemented by hyperkinesis of the remaining normal myocardium, due to acute compensatory mechanisms (including increased sympathetic nervous system activity) and the Frank-Starling mechanism.

Clinical Presentation

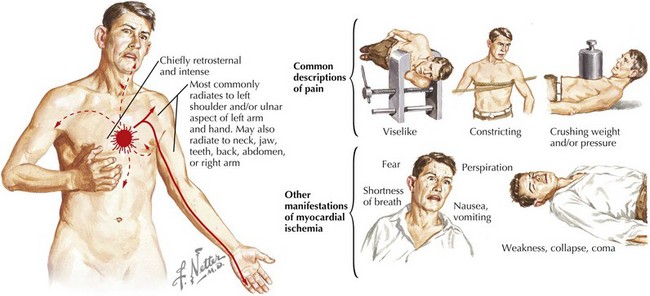

Typical prodromal symptoms are present in many but not all patients who present with an acute MI. Of these, chest discomfort, resembling classic angina pectoris but occurring at rest or with less activity than usual, is the most common. The intensity of MI pain is variable, usually severe, and in some instances intolerable. Pain is prolonged, usually lasting more than 30 minutes and frequently lasting for hours. The discomfort is typically described as constricting, crushing, oppressing, or compressing. Often, the patient complains of a sensation of a heavy weight on or a squeezing in the chest. The pain is usually retrosternal, frequently spreading to both sides of the anterior chest, with predilection for the left side. Often the pain radiates down the ulnar aspect of the left arm, producing a sensation in the left wrist, hand, and fingers. In some instances, pain of an acute MI may begin in the epigastric area and simulate a variety of abdominal disorders. In other patients, MI discomfort radiates to the shoulders, upper extremities, neck, jaw, and even the interscapular region. In patients with preexisting angina pectoris, the pain of infarction usually resembles that of angina. However, it is generally much more severe, lasts longer, and is not relieved by rest and nitroglycerin (Fig. 14-2). In some patients, particularly the elderly, an MI is manifested clinically not by pain but by symptoms of acute left ventricular (LV) failure and chest tightness or by marked weakness or frank syncope. These symptoms may be accompanied by diaphoresis, nausea, and vomiting. More than 50% of patients with ST-segment elevation and severe chest pain experience nausea and vomiting, presumably from activation of the vagal reflex or from stimulation of LV receptors as part of the Bezold-Jarisch reflex. These symptoms are more common in patients with an inferior MI than in those with an anterior MI.

Diagnostic Approach

Electrocardiographic Findings

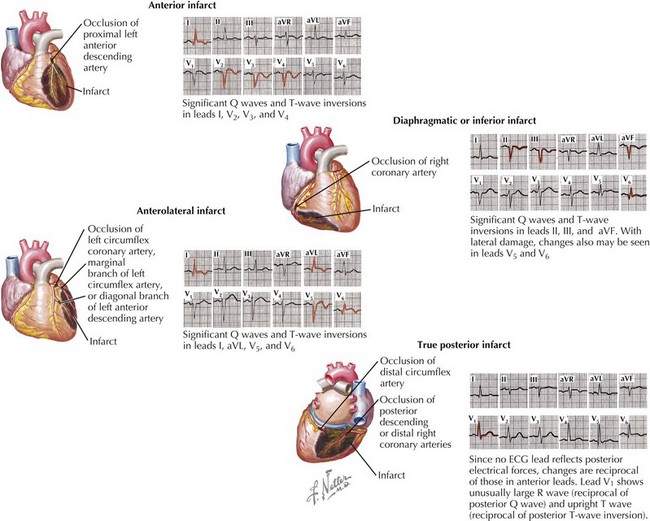

A pattern of ST-segment elevation, especially with associated T-wave changes and ST depression in another anatomic distribution (“reciprocal changes”), combined with chest pain persisting longer than 20 minutes is highly indicative of STEMI (Fig. 14-3). To meet the ECG criteria for STEMI the ST segment must be elevated in at least two contiguous leads by more than 0.2 mV in V1 and V2 in men (0.15 mV in women) and/or by more than 0.1 mV in other leads. Many factors limit the ability of ECGs to diagnose and localize an MI: the extent of the myocardial injury, the age of the infarct, the infarct’s location (e.g., the 12-lead ECG is relatively insensitive to infarction in the posterolateral region of the left ventricle), conduction defects, previous infarcts or acute pericarditis, changes in electrolyte concentrations, and the administration of cardioactive drugs. In addition, some patients with an acute MI do not have significant ST changes because of the location of the infarction. For these reasons, even in the absence of STEMI ECG criteria, severe myocardial ischemia necessitating therapy may be present (see Chapter 13). With an appropriate clinical history, it may be necessary to pursue further diagnostic testing to rule out acute MI.