1 The History and Physical Examination

The History

Chest Discomfort

Determining whether chest discomfort results from a cardiac cause is often a challenge. The most common cause of chest discomfort is myocardial ischemia, which produces angina pectoris. Many causes of angina exist, and the differential diagnosis for chest discomfort is extensive (Box 1-1). Angina that is reproducible and constant in frequency and severity is often referred to as stable angina. For the purposes of this chapter, stable angina is a condition that occurs when CAD is present and coronary blood flow cannot be increased to accommodate for increased myocardial demand. However, as discussed in Chapters 12 through 14, there are many causes of myocardial ischemia, including fixed coronary artery stenoses and endothelial dysfunction, which leads to reduced vasodilatory capacity.

Box 1-1 Differential Diagnosis of Chest Discomfort

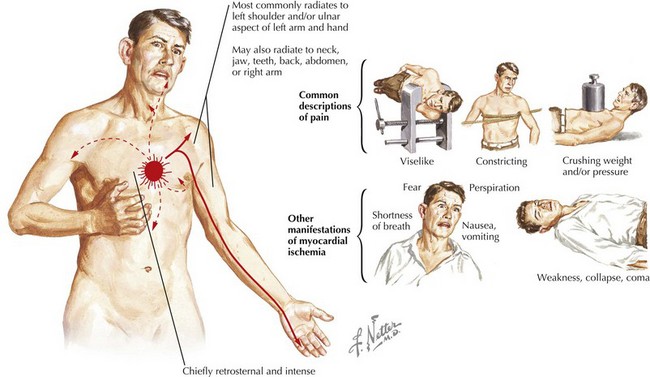

A description of chest discomfort can help establish whether the pain is angina or of another origin. First, characterization of the quality and location of the discomfort is essential (Fig. 1-1). Chest discomfort because of myocardial ischemia may be described as pain, a tightness, a heaviness, or simply an uncomfortable and difficult-to-describe feeling. The discomfort can be localized to the mid-chest or epigastric area or may be characterized as pain in related areas, including the left arm, both arms, the jaw, or the back. The radiation of chest discomfort to any of these areas increases the likelihood of the discomfort being angina. Second, the duration of discomfort is important, because chest discomfort due to cardiac causes generally lasts minutes. Therefore, pain of very short duration (“seconds” or “moments”), regardless of how typical it may be of angina, is less likely to be of cardiac origin. Likewise, pain that lasts for hours, on many occasions, in the absence of objective evidence of myocardial infarction (MI), is not likely to be of coronary origin. Third, the presence of accompanying symptoms should be considered. Chest discomfort may be accompanied by other symptoms (including dyspnea, diaphoresis, or nausea), any of which increase the likelihood that the pain is cardiac in origin. However, the presence of accompanying symptoms is not needed to define the discomfort as angina. Fourth, factors that precipitate or relieve the discomfort should be evaluated. Angina typically occurs during physical exertion, during emotional stress, or in other circumstances of increased myocardial oxygen demand. When exercise precipitates chest discomfort, relief after cessation of exercise substantiates the diagnosis of angina. Sublingual nitroglycerin also relieves angina, generally over a period of minutes. Instant relief or relief after longer periods lessens the likelihood that the chest discomfort was angina.

Although the presence of symptoms during exertion is important in assessing CHD risk, individuals, especially sedentary ones, may have angina-like symptoms that are not related to exertion. These include postprandial and nocturnal angina or angina that occurs while the individual is at rest. As described herein, “rest-induced angina,” or the new onset of angina, connotes a pathophysiology different from effort-induced angina. Angina can also occur in persons with fixed CAD and increased myocardial oxygen demand due to anemia, hyperthyroidism, or similar conditions (Box 1-2). Angina occurring at rest, or with minimal exertion, may denote a different pathophysiology, one involving platelet aggregation and clinically termed “unstable angina” or “acute coronary syndrome” (see Chapters 13 and 14).

When considering the likelihood that CHD accounts for a patient presenting with chest discomfort or any of the aforementioned variants, assessment of the cardiac risk factor profile is important. The Framingham Study first codified the concept of cardiac risk factors, and over time, quantification of risk using these factors has become an increasingly useful tool in clinical medicine. Cardiac risk factors determined by the Framingham Study include a history of cigarette smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, or hypercholesterolemia; a family history of CHD (including MI, sudden cardiac death, and first-degree relatives having undergone coronary revascularization); age; and sex (male). Although an attempt has been made to rank these risk factors, all are important, with a history of diabetes mellitus being perhaps the single most important factor. Subsequently, a much longer list of potential predictors of cardiac risk has been made (Box 1-3). An excellent, easy-to-use model for predicting risk is the Framingham Risk Calculator, as described in the Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (see “Evidence” section).

Box 1-3 Cardiac Risk Factors

Determining whether the patient has stable or unstable angina is as important as making the diagnosis of angina. Stable angina is important to evaluate and treat, but does not necessitate emergent intervention. Unstable angina, or acute coronary syndrome, however, carries a significant risk of MI or death in the immediate future. The types of symptoms reported by patients with stable and unstable angina differ little, and the risk factors for both are identical. Indeed, the severity of symptoms is not necessarily greater in patients with unstable angina, just as a lack of chest discomfort does not rule out significant CHD. The important distinction between stable and unstable coronary syndromes rests in whether the onset is new or recent and/or progressive (e.g., occurring more frequently or with less exertion). The initial presentation of angina is, by definition, unstable angina; although for a high percentage of individuals this may merely represent the first recognizable episode of angina. For those with unstable angina, the risk of MI in the near future is markedly increased. Likewise, when the patient experiences angina in response to decreased levels of exertion or when exertional angina has begun to occur at rest, these urgent circumstances require immediate therapy. The treatment of stable angina and acute coronary syndrome is discussed in Chapters 12, 13, and 14. The Canadian Cardiovascular Society Functional Classification of Angina Pectoris is a useful guide for everyday patient assessment (Box 1-4). Categorizing patients according to their class of symptoms is rapid and precise and can be used in follow-up. Class IV describes the typical patient with acute coronary syndrome.