TABLE 78.1 Rate of Positivity, Pulmonary Squamous Cell Carcinomas, Selected Immunohistochemical Markers | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

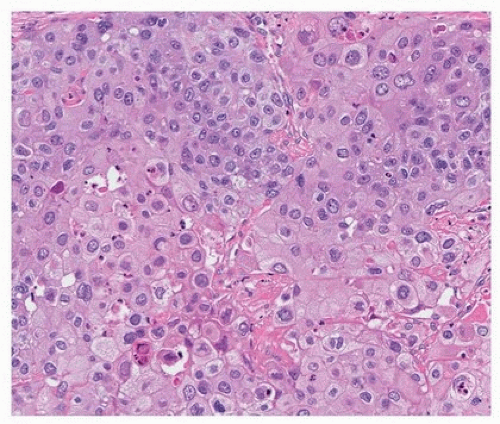

without glandular structures or mucin vacuoles (Figs. 78.3 and 78.4). Nonkeratinizing, poorly differentiated tumors may have a basaloid appearance (see below) or resemble adenocarcinomas with a solid growth pattern, in which case immunohistochemical stains are necessary for a definitive diagnosis. Proximal tumors tend to have a papillary or endophytic growth pattern (Fig. 78.5). Peripheral tumors grow in two overlapping patterns: one that respects alveolar architecture, filling alveolar spaces (Fig. 78.6), and one that is accompanied by fibrosis, with a pushing, destructive edge (Fig. 78.7).8,22 Peripheral tumors are more likely to have vascular (Fig. 78.8) and pleural invasion and less likely to be associated with squamous metaplasia in adjacent bronchi than proximal tumors.10 There may be large areas of cytoplasmic clearing due to intracytoplasmic glycogen (Fig. 78.9), a nonspecific finding that is common in both squamous and adenocarcinoma. Squamous carcinomas may grow along alveolar walls, a pattern that is often confused with adenosquamous carcinoma. This growth pattern has been termed “endoalveolar growth” or “invasion along alveolar walls” and is seen in up to 20% of squamous carcinomas.23,24

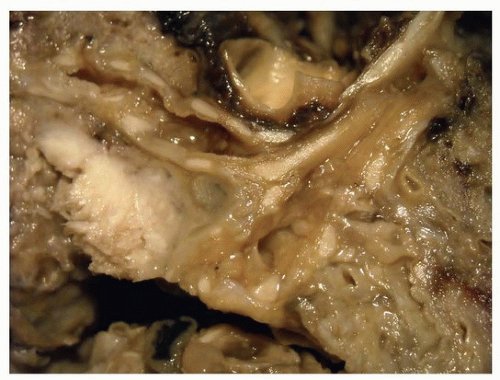

FIGURE 78.1 ▲ Squamous cell carcinoma. The tumor distorts the bronchial surface and invades the adjacent lung. |

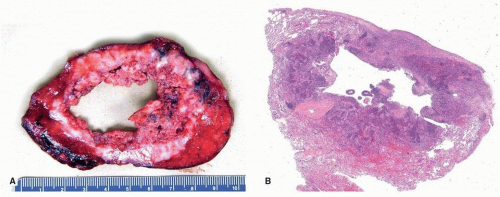

FIGURE 78.2 ▲ Squamous cell carcinoma. Approximately 20% of tumors, especially those that are central, form cavitary masses. A. Gross photograph. B. Corresponding histologic section. |

FIGURE 78.3 ▲ Squamous cell carcinoma. Tumor forms cohesive sheets with scattered dyskeratotic cells. |

lacks specificity (Table 78.2). δNp63 (p40) is of similar sensitivity as p63, but more specific, as it is less likely expressed in adenocarcinomas and neuroendocrine carcinomas than p63.26 For this reason, it has largely replaced p40 in distinguishing poorly differentiated squamous from adenocarcinomas of the lung. Cytokeratin 5/6 is nearly as sensitive and specific as p40 and is often used in panels that include other markers in the distinction between squamous and other carcinomas of the lung.11,12,13

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree