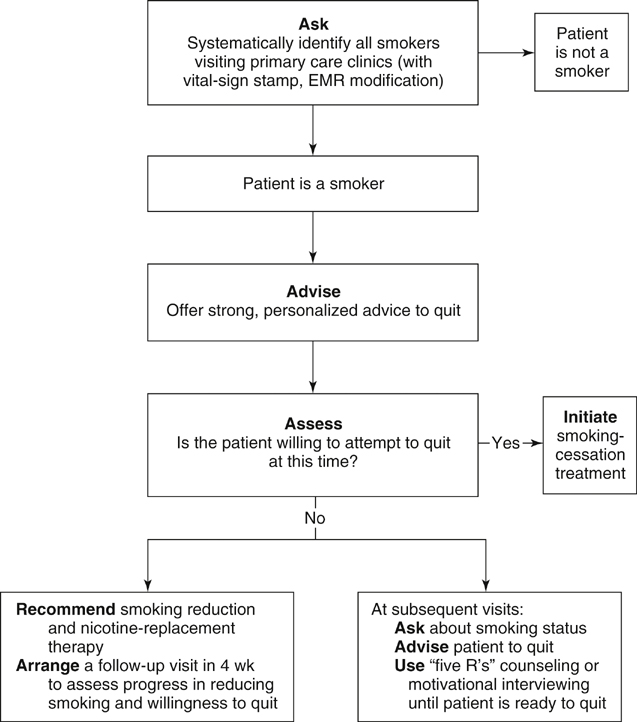

Randomized studies have shown that a significant percentage of smokers can be recruited to quitting and that quit rates are much higher among this group. For those smoking patients unwilling to pursue quitting, a number of approaches should be used. It is important to encourage those unwilling to quit to decrease smoking as much as possible. It is also felt to be effective to recommend nicotine-replacement therapy, such as nicotine patch or gum, even before attempts at smoking cessation are made. The provider should express acceptance of the patient’s reluctance to quit, but informational support, as well as an empathic, supportive discussion, is a recommended strategy. Finally, it is important to reduce barriers to treatment as much as possible. Arranging prompt follow-up, making repeated offers to assist in quitting, and making smoking-cessation counseling available within the same facility as patient visits can all make smoking cessation more likely to occur. The combination of motivational interviewing, smoking reduction, and nicotine-replacement therapy is thought to increase the chances of successful quitting (Figure 1).

Smoking Cessation

Motivating Patients to Quit

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine