Polysomnography in severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS). Lines represent 60 s of sleep N2. Two obstructive events are shown (in red). Desaturations (in green) can be observed toward the end of the obstructive events

Physiopathological mechanisms associated with the described consequences of SDB are fundamentally sleep disruption, intermittent night hypoxemia, and chronic inflammation of the airway.

Epidemiology

The prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing (SDB) is estimated to be about 10–20%, and OSAS prevalence is estimated to be about 1% in children under 15 years old. These numbers fluctuate from region to region, and the prevalence is higher in Afro-American and Hispanic populations. Multiple risk factors affect the prevalence of SDB, and the sociodemographic factor is an important one. These factors are more frequent in children of lower socioeconomic status, premature, and obese. The prevalence of OSAS linearly varies according to the body mass index of the patients studied, and it was present in about 60% of morbidly obese patients. In Chile, studies have shown an SDB prevalence of 18% in the pediatric population.

Physiopathology

Ventilation control that regulates upper airway tone and awakening response; both physiologically decrease during sleep.

Residual functional capacity decreases and may cause hypoxemia and apnea, which is caused by a reduction of the intercostal muscular and upper airway tone, especially during REM sleep.

The tone of the upper airway tract is reduced during sleep and causes an increase of its resistance, which at the same time may impact ventilation and gas exchange.

Progressively, and as a result of the aforementioned phenomena, hypoxemia and hypercarbia will be present during sleep. This physiological phenomenon worsens if it coexists with any other lung or airway disease.

Besides this, children with OSAS tend to have an airway with reduced space. They generally present with a narrowing of the airway related to intermittent hypercarbia and hypoxia. The site of greater obstruction tends to be more distal than in adults, usually including the oropharynx and hypopharynx. Children with this symptom have inspiratory aphasic activity in the muscles of the upper tract of the airway during sleep.

Infants and children normally have a narrower airway than adults. Nevertheless, they usually snore less and show fewer obstructive apneas in comparison to adults, which could be explained by anatomical differences and also by a different muscular tone of the upper airway. Critical pressure reflects the balance between the anatomical structure and the muscle tone of the airway; however, it is very difficult to determine a critical pressure in children as the airway is very resistant to collapse, probably because children have a greater ventilatory drive. Because of this, it is possible that children have greater activation of the muscles of the upper airway when responding to different stimuli.

The upper airway in children with OSAS is more collapsible in comparison to control children without this syndrome, for both awake or sleep and anesthesia periods. A series of mechanisms may create a greater degree of collapsibility in these patients, among which we can mention lower muscle tone, increase of airway distensibility, and increase in the inspiratory pressure, caused by the narrowing of the proximal airway.

A recent study used magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate the changes in the shape and size of the sectional area in the airway during breathing at tidal volume. In this study, it was shown that children with this syndrome have greater fluctuations in the airway when compared to control subjects. The explanations for this can lie in a reduced distensibility or a greater resistance. Studies that have involved the denervated upper airway have shown that lack of muscle tone may cause a greater collapse. It was recently proven that children have active upper airway responses to both negative pressures and hypercapnia during sleep. Healthy children could compensate the small size of the airway by increasing ventilatory command. This compensation mechanism could be reduced or absent in children with this syndrome.

To summarize, a combination of the structure of the airway with neuromuscular control, besides other genetic, hormonal, and metabolic factors, cause the appearance of OSAS in children.

Physiopathological Consequences

This increase could be a factor that causes poor growth in children with OSAS. As a result of the greater diagnosis and consciousness about this syndrome, most children are detected before they can present any lack in their growth, and currently it is very infrequent.

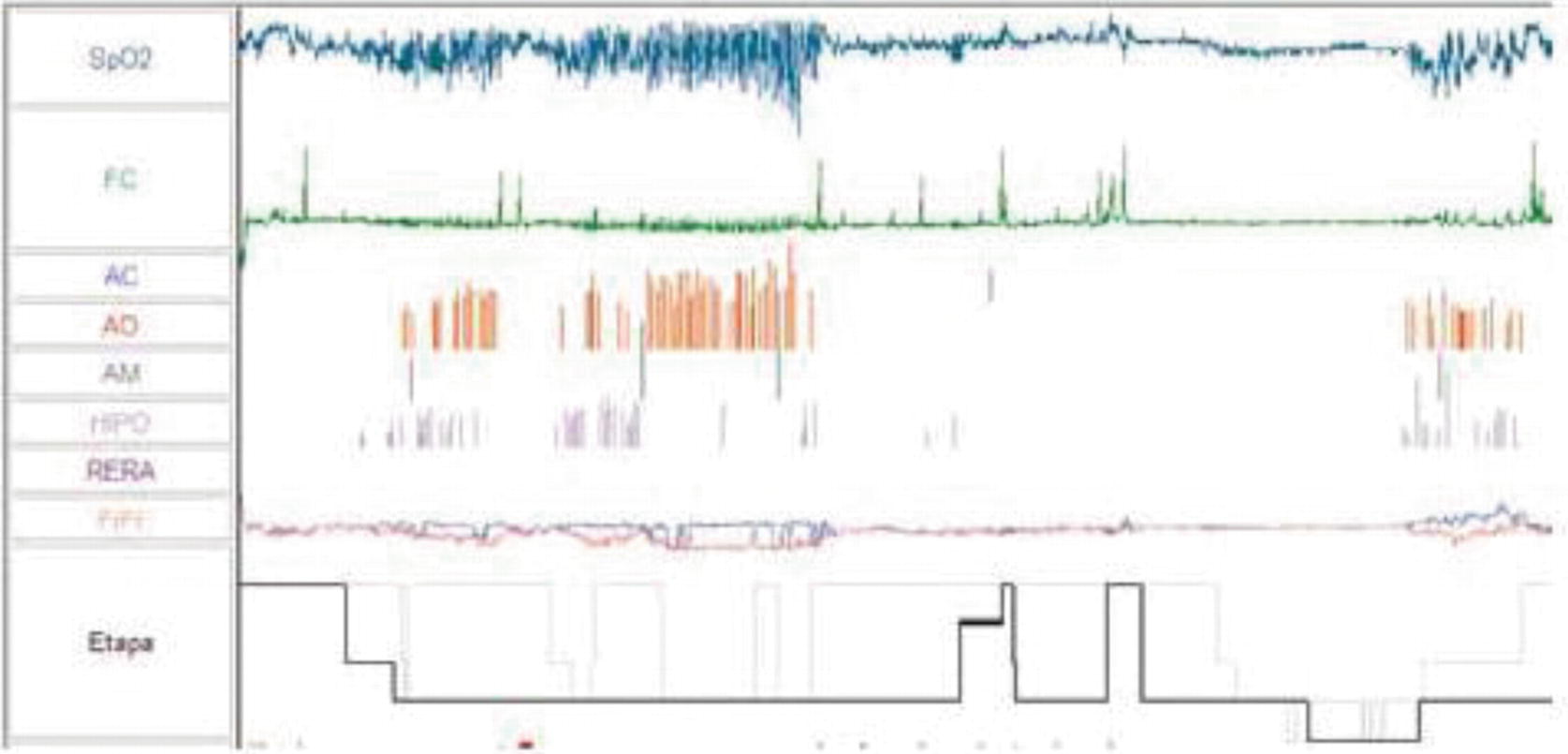

Hypnogram in severe OSAS. Record of 4 h in a 1-year-old patient showing frequent obstructive events (in red) and cluster desaturations (in green)

Sleep fragmentation is a well-documented consequence of OSAS in adults, but it is not yet fully understood in children. Although micro-awakenings have a protective role in this syndrome, their increase in frequency can cause a disruptive sleep instead of a reparative one. Sympathetic activation, as well as the activation of secondary inflammation mediators, has similar or even worse consequences than intermittent hypoxemia. The identification of micro-awakenings in adults is based on ECG interpretation. In contrast, in children more variables have to be considered, as most micro-awakenings are subcortical and are not necessarily observable through ECG.

Associated with OSAS, alveolar hypoventilation is the result of long periods of upper airway increased resistance and hypercapnia, with or without hypoxemia. In the end, this causes long-term effects in the neural tissue and vasomotor tone. CO2 increase is the main characteristic of this condition.

Clinical Presentation

Nighttime Symptoms

Symptoms Related to OSAS in Children

Daytime |

Behavioral problems |

Hyperactivity |

Belligerence |

Poor school performance |

Lack of appetite |

Daytime sleepiness |

Poor concentration |

Nighttime |

Snoring |

Respiratory distress |

Apnea as reported by parents or caregivers |

Nonrestful sleep |

Frequent awakenings |

Night sweats |

Night enuresis |

Such distress is a subjective manifestation usually informed by the parents of children with OSAS. Usually, they describe paradoxical respiratory movements in which “the abdomen lowers, while the chest rises.”

Parents frequently describe breathing stops during sleep, and some of them mention that respiratory noises stop for a few seconds, which are followed by a “grunt” or energic breathing.

These three cardinal symptoms are the most consistent ones in children with this syndrome. At the beginning of the 1980s, Brouillete et al. used these to create the “OSA Score.” This score states that those children who snore every night had sleep respiratory distress, and those whose parents have witnessed apneas would have OSAS. Although the predictive positive value was acceptable (50–75%), this was not true for the predictive negative value (25–80%).

Unrestful sleep is the consequence of repeated micro-awakenings during sleep. Parents usually describe a child who moves and has diverse postures during sleep, sometimes with the head in hyperextension.

Such awakenings are a commonly reported clinical situation. At first, parents may believe that this is related to behavior, hunger, or thirst during sleep.

Night sweats are the result of respiratory distress during sleep and micro-awakenings and movements. It can be observed in an important number of children affected.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree