Chapter 21 Severity Scoring and Outcomes Measurement

Historical Background

With these words from 1775, Patrick Henry set a standard for the role of progress. Moving forward demands a look back and a commitment not to abandon the lessons of the past to the lure of an untested future.1

The approach to accepting change and advancement in medicine and surgical technology is much the same. The promises of the new must meet the expectations built from the experience of the old. The responsibility of the physician is to rigorously evaluate new developments through analysis of data and to share those findings with his or her patients and other physicians.1

There is evidence of the recognition of varicose veins as early as ancient Egyptian and Greek periods, including a familiar tablet in Athens, Greece, of a man displaying a leg with visible varicosities.2 Other writings have offered descriptive accounts of circulation, arteriography and venography, the introduction of heparin, and the embolectomy catheter. From Oribasius in the fourth century, who also wrote about surgical procedures for varicose veins, to Harvey in the 17th century, these writings described in detail the structure and function of the circulatory system.

In an article about the discovery of venous valves, Scultetus et al. wrote: “With the formidable advances of the diagnostic methods and new therapeutic modalities, we will be able to make earlier diagnoses, begin treatment sooner, and increase life expectancy. However, we must not forget the origin of our knowledge—the past.”3

The end of the 20th century and the first decade of the 21st century have marked a change of focus in venous disease and therapy. Although treatments were regularly being offered for many vascular conditions, the outcomes were only sporadically evaluated. After introducing several valvular reconstructive procedures, Kistner found that reporting methods were not standardized across facilities, preventing interinstitutional trials and confounding results reporting.4 According to Mozes and Gloviczki, “The time has come to standardize the clinical classes of venous disease, to compare treatment and outcome, and to speak the same language when we talk about venous problems all around the world.”5

This realization that the language of diagnostic and treatment information needs to be universal has shifted the focus of physicians to organize information to provide a framework for clinical practice and research.4 Dayal and Kent6 wrote about the need for reporting standards to address important elements of assessment, including clinical classification of disease, a grading system for risk factors, categorization of operations and interventions, complications encountered with grades for severity or outcomes, and criteria for improvement, deterioration, and failure.

Results should be evaluated alongside other options such as the natural course of the disease itself, nonsurgical therapies, additional surgical interventions, or alternative ways of performing an intervention.7 Developing and using proper outcomes assessment tools should be paramount in the minds of those treating venous disease. The assessment of outcomes in chronic venous disease is multifactorial and is more complicated than in other vascular conditions.8 The end points of comparison must be objective usable measures that reflect signs, symptoms, and patient quality of life.9 Rutherford said, “Comparing results is not a simple matter, but if we develop a good, readily usable approach to outcomes comparisons, one by which the results of our labors can be properly judged, the results are great.”7

Etiology and Natural History

In the 1950s, life table analysis was used to examine and predict survival and success rates from many surgical procedures. When the concept was applied to cancer survival in the mid 1970s, it gained acceptance as a valid reporting method for outcomes assessment.10 Reports of short- and long-term survival after procedures for lower extremity ischemia became more common in the 1970s and 1980s, culminating in the 1986 findings of an ad hoc committee of the Society for Vascular Surgery/North American Chapter, International Society for Cardiovascular Surgery.11 This group was charged with standardizing reporting practices for lower extremity ischemia. It was one of several subcommittees that met to determine reporting standards for numerous vascular conditions and therapies. Around this same time, reports were being published on clinical outcomes and quality-of-life assessment. Many of the instruments used were able to be applied to the emerging field of venous disease.

The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) is a generic quality-of-life survey developed from components of multiple surveys used in the 1970s and 1980s. It was first used in a developmental form in 1988 and in a standard form in 1990. It is designed to assess physical health (the patient’s level of functioning) and mental health (an indication of well-being) by breaking these categories into eight domains: physical and social functioning, role limitations because of physical or emotional problems, mental health, pain, vitality, and perception of health. This survey has been widely used and validated in small and large studies, most notably the Bonn Vein Study.11a This German study evaluated 3072 participants and was designed to determine the rate of occurrence and severity of chronic venous disease among the general public. The SF-36 was useful in this study because of its specific objectives. Patients were enrolled from the community without prior knowledge of their venous disease status. By using the reliability and validity of the SF-36 along with physical examinations, it was possible to determine the rate of occurrence of chronic venous disease and its effect on several quality-of-life variables. The International Quality of Life Assessment Project aims to translate and adapt the SF-36 into all major languages. If this undertaking is successful, the SF-36 will gain strength internationally as a measure of health-related quality of life.12,13

In addition to generic measures, patient-reported disease-specific instruments have been used extensively in reporting chronic venous disease and therapy. A patient-reported outcome (PRO) is any report of patient health condition made by the patient and reported as said, without physician interpretation. Such an instrument can be used during the diagnostic phase to measure symptoms or disease states and following therapy to evaluate changes and treatment effect. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommends the use of a PRO instrument when the element being measured is best known and expressed by the patient.14

The Chronic Venous Insufficiency Questionnaire (CIVIQ) has had two versions. The first version, CIVIQ 1, was developed in French in 1994, and it was validated in English between 1997 and 1999 in the Reflux Assessment and Quality of Life Improvement with Micronized Flavonoids study.15 The survey evaluated physical, psychological, social, and pain effects. Different numbers of questions were asked in each category, rendering the instrument difficult to score. A revised version, CIVIQ 2, equally distributed the effects across 20 questions to provide a composite score. Both versions of the CIVIQ have been used and validated.12

The Venous Insufficiency Epidemiological and Economic Study (VEINES) instrument was validated in 2006. It consists of 35 items in two categories to generate two summary scores, one for quality of life and another for symptoms. The quality-of-life survey has 25 items that estimate the effect of disease on quality of life, and the symptom survey has 10 items that measure symptoms. The focus is on physical manifestations rather than psychological and social elements. Along with score division into categories of symptoms and disease effect, this makes the VEINES instrument useful for many clinical applications. The VEINES has been validated in four languages.12

The Aberdeen Varicose Vein Questionnaire is a 13-question survey developed in 1993 addressing all elements of varicose vein disease. Examined are physical and social issues, including pain, ankle edema, ulcers, and the use of compression therapy as well as the effect of varicose veins on daily life and as a result of cosmetic issues. It is scored from 0 (no effect) to 100 (maximum effect). Specifically addressing the effect of varicose veins on quality of life, including cosmetic impact, this questionnaire was designed to improve the sensitivity of response among all patients, even those with less severe physical symptoms. This survey has been validated and used for all types of venous disease.12,16

The Charing Cross Venous Ulceration Questionnaire was developed and validated in 2000 to provide a quality-of-life measure for patients with venous ulcers. Before the existence of this instrument, there was no standardized measure of the effects of treatment for venous ulcers. The survey contains 20 questions scored from 0 (no effect) to 5 (maximum effect). The instrument is scored from the sum of these individual question scores. It has been validated and used in patients with ulcers.12,17

The Specific Quality of Life and Outcome Response–Venous (SQOR-V) survey was initially validated in French in 2007 and was continuing to undergo validation in English in 2010. It differs from the other patient-reported surveys in its focus on the relationship between the patient’s primary complaint and his or her venous disease. It groups questions regarding symptoms, cosmesis, effect on activities and habits, and worry about the health implications of venous disease. Most of its 15 questions are broken into specific subcategories to elucidate thorough information about each aspect of the patient’s concerns.12,18

The CEAP classification was developed in 1994 as a common descriptive platform for the reporting of diagnostic information in chronic venous disease. The clinical component is scored for active disease severity from 0 (none) to 6 (active ulcers). The etiology section categorizes the venous disease as congenital, primary, or secondary. The anatomic classification identifies affected veins as superficial, deep, or perforating. The pathophysiologic section details the presence or absence of reflux in the superficial, communicating, or deep veins and any incidence of outflow obstruction. The revised CEAP classification, published in 2004, is widely used as the reporting standard in venous disease but is not without drawbacks. Although an excellent descriptive tool, the revised CEAP classification is static and is limited in its ability to reflect response to treatment, especially in the C4 and C5 categories.12 This is most evident if the CEAP classification is used as a stand-alone instrument.

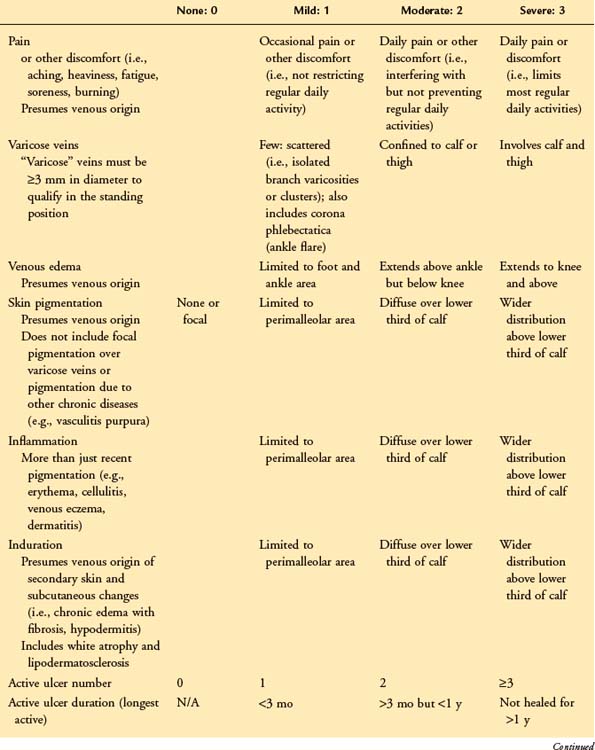

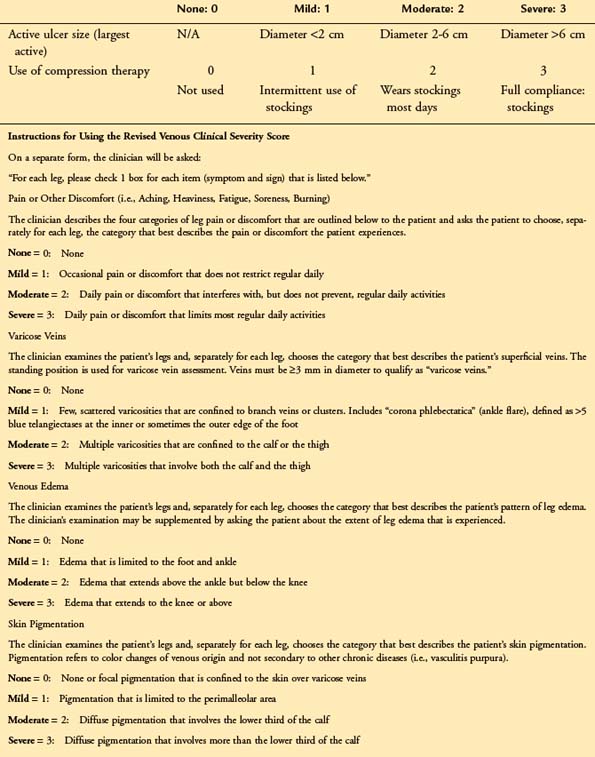

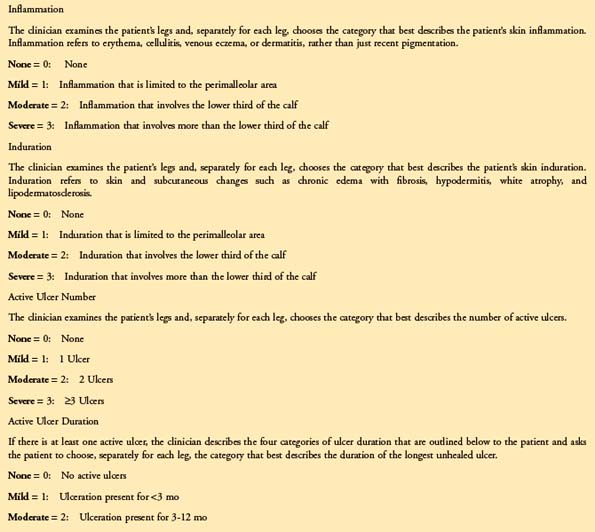

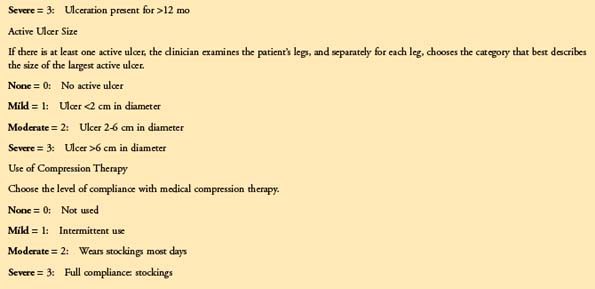

The VCSS was designed in 2000 by a committee of experts to include nine recognized features of venous disease. Each is scored from 0 to 3. The recently revised VCSS19 updates terminology, clarifies application, and combines important language of PROs to reflect severity changes across the spectrum of symptomatic venous disease. The feature that sets the revised VCSS apart from other physician-assessed instruments is its ability to reflect status changes in response to therapy. This is owing to the nature of the categories, which are broken down into elemental aspects of venous disease. The clinical descriptors include vein size and location, the use of compression therapy, skin changes (including pigmentation, inflammation, induration, and ulcers), and edema and its distribution as noted by the patient at different points in the day and by the physician; pain is identified as being “aching, heaviness, fatigue, soreness, and burning.” The revised VCSS is thought to have retained its sensitivity, while better identifying issues of patients with milder venous disease (Table 21-1). The course of outcomes assessment thus far has offered two choices for the type of assessment performed: physician assessed and patient reported. The data derived from physician-assessed instruments may not always be an indication of the effect of disease or the value to the patient of the changes following treatment, even seemingly slight improvements.20,21 However, valuable data can be generated much more readily with little burden to the clinician. Input of these data into available online registries in the United States and in Europe is important to ensure that new therapies meet high standards of safety and reliability and that they address the variables considered important to the physician and the patient.21,22

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree