Secondary Pulmonary Hypertension

Allen P. Burke, M.D.

General

Pulmonary hypertension secondary to heart and lung diseases is common (Table 64.1) compared to idiopathic and associated pulmonary arterial hypertension, which are relatively rare (Chapter 63). Postcapillary pulmonary hypertension is the result of pulmonary venous hypertension, usually caused by left-sided heart disease. Pulmonary parenchymal diseases, especially chronic obstructive lung disease, are frequent causes of pulmonary hypertension (see Chapter 44) related to hypoxia and destruction of the capillary bed. The most common form of secondary precapillary hypertension is that of recurrent embolism.

Signs and symptoms of secondary pulmonary hypertension are similar to those of primarily pulmonary hypertension but are often less severe. In addition, there are clinical and pathologic features related to the underlying disorder.

In general, plexiform lesions are not considered a feature of secondary pulmonary hypertension. In fact, the reported finding of plexiform lesions in pulmonary hypertension secondary to HIV, schistosomiasis, and sickle cell disease has led to their placement from “secondary” to “associated” pulmonary arterial hypertension, similar to connective tissue diseases and portopulmonary hypertension.1

Pulmonary Hypertension Secondary to Heart Disease

Left heart disease probably represents the most frequent cause of pulmonary hypertension.1 The mechanism involves increased left atrial pressures. In contrast to arterial hypertension, pulmonary, vascular resistance is normal or near normal. Left heart disease that results in pulmonary hypertension includes systolic dysfunction, diastolic dysfunction, and mitral valve disease.

TABLE 64.1 WHO Classification of Secondary Pulmonary Hypertension1 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

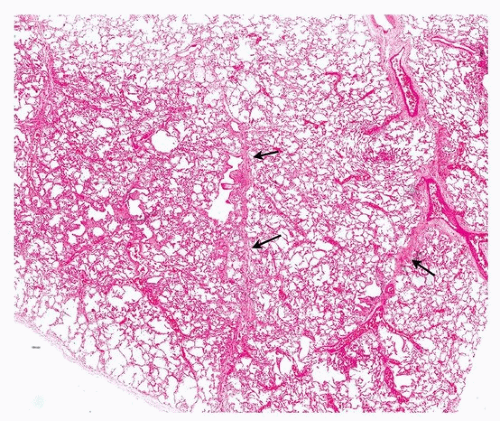

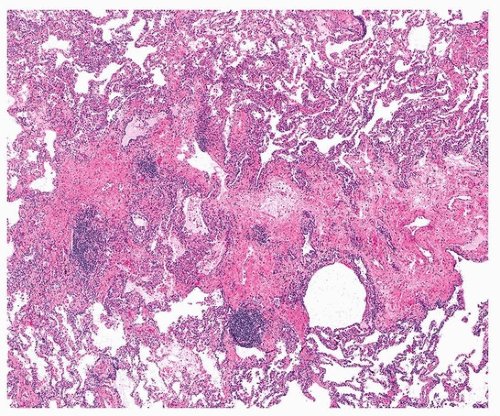

Pathologically, there is edema and fibrosis in the interlobular septa, with thickening of veins (Figs. 64.1 and 64.2). In contrast to pulmonary venoocclusive disease, thrombi are absent in veins. There is typically mild thickening of alveolar walls due to capillary congestion. Intraalveolar edema fluid and scattered hemosiderin macrophages (heart failure cells) are commonly present (Fig. 64.3).

Vascular changes include medial thickening of muscular arteries and eccentric or concentric intimal thickening, which is typically bland and relatively acellular. Concentric rings of elastic tissue and plexiform lesions are not a feature of pulmonary venous hypertension.

Pulmonary Hypertension Related to Lung Disease and/or Hypoxia

The predominant cause of pulmonary hypertension in this category is alveolar hypoxia. This may occur secondary to intrinsic lung disease, especially emphysema and interstitial fibrosis; secondary to impaired control of breathing, as in obstructive sleep apnea; or secondary to residence at high altitude.

FIGURE 64.1 ▲ Pulmonary venous hypertension, secondary to mitral valve stenosis. Low magnification demonstrates interlobular septal thickening (arrows). |

FIGURE 64.2 ▲ Pulmonary venous hypertension, secondary to mitral valve stenosis. In this case, the septal fibrosis is marked. |

The degree of pulmonary hypertension with parenchymal lung disease is generally modest, with mean arterial pressures 25 to 35 mm Hg. In patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who underwent right heart catheterization, only 1% had mean arterial pressures over 40 mm Hg.2 In patients with combined pulmonary fibrosis and emphysema, however, the prevalence of pulmonary hypertension is almost 50%.3

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree