14 Sarcomas and Sarcomatoid Neoplasms of the Lungs and Pleural Surfaces

This chapter summarizes the clinicopathologic information pertaining to such lesions. It devotes exclusive attention to malignant lesions; benign mesenchymal neoplasms of the lung and pleura are discussed in Chapter 19. Pseudotumors are likewise considered in another portion of this book. Nevertheless, those pathologic categories and other lesions will indeed be mentioned here in the context of differential diagnosis. The entities that are discussed are arranged in order of frequency, to give the reader a sense of their relative incidences.

Sarcomatoid Carcinoma of the Lung

Recent changes in the classification of lung tumors have included sarcoma-like tumors. Five subtypes of those lesions are now codified; pleomorphic carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, giant cell carcinoma, carcinosarcoma, and pulmonary blastoma are predicated on the particulars of their microscopic appearances.1,2 We consider all of these neoplasms to be part of the same tumor family, that of sarcomatoid carcinomas (SCs), as discussed in more detail subsequently. Although SCs are rare in an absolute sense, they represent the most common mesenchymal-like malignancies of the airways.3,4 True sarcomas are very infrequently seen in the tracheobronchial tree.4–13 Therefore, one usually considers a cytologically atypical spindle cell tumor of the lung to be an SC unless thorough immunohistological and ultrastructural studies indicate otherwise.5 This review will discuss neoplasms in this general category, using information taken from the pertinent literature as well as the personal experience of the authors.

Historical and Terminologic Considerations

Over time, morphologically similar tumors have been given a variety of designations in the upper and lower respiratory tracts. These diagnostic terms have included blastoma, sarcomatoid carcinoma, spindle cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma with pseudosarcomatous stroma, pseudosarcoma, and carcinosarcoma, based largely on the specific microscopic attributes of the lesions in question and the conceptual leanings of the authors describing them.14–43

More than 70 years ago, Saphir and Vass44 assessed the literature then extant on carcinosarcomas and concluded that they represented primary epithelial malignancies that had undergone divergent differentiation (tumor metaplasia). Their paper cited several lesions of the lung. Thereafter, opposing publications on histogenesis espoused the opinion that biphasic neoplasms of the airways were “collision” tumors, or that they reflected the proliferation of non-neoplastic mesenchymal tissue components that were induced by the carcinomatous elements.45–47 At the turn of the last century, Krompecher48 and others49 had held to the same theories as those of Saphir and Vass. In the past two decades, results of studies using electron microscopy, immunohistology, and “molecular” assays of clonality have tended to support the latter foresighted views of those pioneers convincingly. Hence, it is believed currently that blastomas, carcinosarcomas, carcinomas with pseudosarcomatous stroma, and SCs comprise a single morphological spectrum of basically epithelial tumors, regardless of their anatomic locations.34–36 Biphasic sarcomatoid carcinoma and monophasic sarcomatoid carcinoma have been proposed as replacements for the former designations of carcinosarcoma and spindle cell carcinoma, respectively.33,34,37 In the penultimate iteration of the World Health Organization nosologic scheme, such lesions were included in the category designated “carcinoma with pleomorphic, sarcomatoid, or sarcomatous elements.”36

Clinicopathologic Features of Pulmonary Sarcomatoid Carcinomas

Clinical Attributes

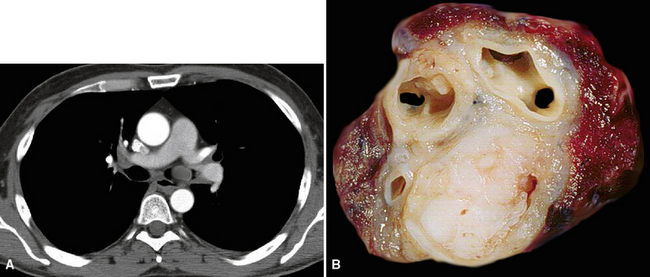

SCs arise in the large bronchi and peripheral lung fields much more often than in the trachea, although the authors have indeed seen some lesions that originated above the carina. The majority of individuals with pulmonary SC are men, and most have a history of heavy smoking.14,23,24 The average patient is 60 years of age.33 Clinical signs and symptoms produced by these tumors are directly associated with the tumor’s specific location. Endoluminal lesions in large tubular airways characteristically cause refractory or recurrent pneumonia in the corresponding distal parenchyma, or they are associated with progressive dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, and audible expiratory rhonchi over the affected lung field.14–17,23,45–47,50,51 In contrast, SC in the peripheral lung often manifests no symptoms or, alternatively, leads to chest pain caused by invasion of the pleura and extrapulmonary soft tissue.23 As might be expected, central endobronchial tumors are smaller than peripheral SCs; their average sizes are 6 cm and greater than 10 cm, respectively46,52 (Fig. 14-1).

Despite their anaplastic nature, SCs of the lung are surgically resectable in roughly 90% of cases,23,33 and approximately one half of patients with such neoplasms present with stage I disease. Paradoxically, however, the prognosis of pulmonary SC is still dismal. Overall 5-year survival is 20%, with a slightly better figure being associated with small, central endobronchial lesions.23,33,52 Metastatic SC of the lung involves the same organ sites that are affected by more usual forms of lung cancer: namely, the opposite lung, liver, bones, adrenal glands, and brain.46,51 The metastases may exhibit either carcinomatous or sarcoma-like histologic configurations, or both.46 Adjuvant radiation treatment and chemotherapy have been used in many cases of pulmonary SC, but these measures have provided little benefit in general.14,33,38

Macroscopic Features

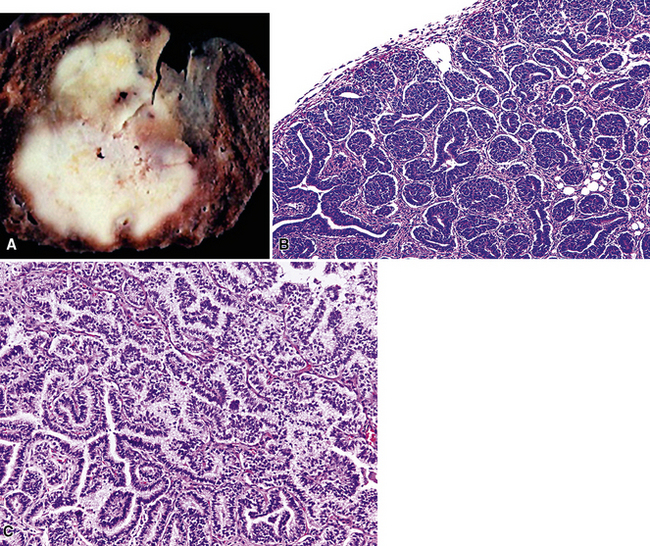

Grossly, the lesions of pulmonary SC that are greater than 5 cm in size tend to exhibit central necrosis and hemorrhage, and they also demonstrate irregular permeation of the surrounding lung parenchyma33,34 (Fig. 14-2). Tumors that are smaller and located within bronchial confines often exhibit a polypoid appearance and are attached to the subjacent mucosa by a relatively narrow stalk of tissue.52 SCs in the peripheral lung parenchyma may have the gross appearance of conventional adenocarcinomas.34

Histologic Characteristics

Homologous Biphasic Sarcomatoid Carcinoma

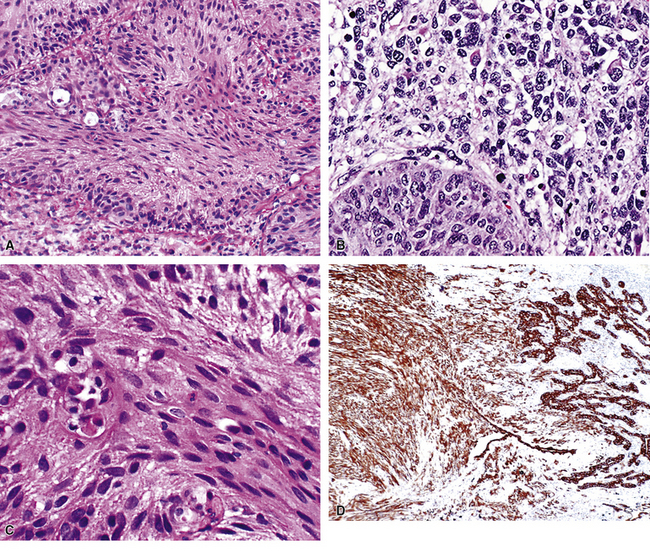

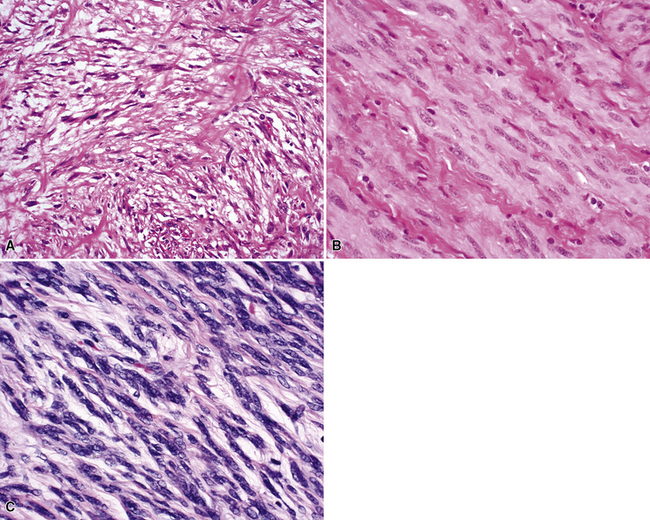

Variants of SC that are also called spindle cell carcinomas are constituted microscopically by a predominance of nondescript spindled and pleomorphic cells, admixed with a minor, obviously carcinomatous, component. The latter portion of such lesions is generally inconspicuous and variably distributed; in roughly 40% of cases, such foci are very rare and require extensive sampling to document their presence. The general appearance of the carcinomatous elements is that of a well- to moderately differentiated squamous malignancy in most instances, whereas adenosquamous, adenocarcinomatous, large cell undifferentiated, or neuroendocrine carcinoma is seen in a minority of cases14,53–56 (Fig. 14-3). Rare examples of this tumor type show mixtures of several carcinoma morphotypes.54 Zones of transition between epithelial and sarcoma-like components are usually evident, at least focally.

The sarcomatoid elements of this subtype of SC lack specialized differentiation into identifiable myogenic, chondro-osseous, or vasoformative tissues by standard light microscopy, and, as such, are homologous (organ-appropriate) to the lung. They are composed of markedly heterogeneous cells with nuclear atypia and variable growth patterns. The corresponding microscopic images range from those of fibromatosis-like or low-grade fibrosarcoma-like areas, with relatively bland nuclear features, sparse mitoses, moderate-to-rich matrical collagen deposition, and a “herringbone” pattern, to others in which pleomorphic giant cells are mixed with fusiform elements showing dense cellularity, coarse chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and numerous mitoses14–16,23,33,45 (Fig. 14-4). The last of these descriptions is closely similar to that attending spindle cell–pleomorphic malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) of the soft tissues.54 Neoplastic spindle cells often infiltrate the submucosa of small- and medium-sized bronchi, which nonetheless tend to retain their mural cartilage plates and mucosal integrity.33,34

Sarcoma-like elements in some biphasic spindle cell carcinomas may include cytologically bland, osteoclast-like giant cells52,57,58 (Fig. 14-5). The latter are admixed with atypical fusiform cells or more uniform polygonal tumor cells. Another variant histologic pattern is that in which bluntly fusiform tumor cells surround discrete zones of necrosis, producing a necrotizing granuloma-like image. Rare examples of SC may demonstrate extravasated erythrocytes between relatively bland spindled tumor cells, simulating the characteristics of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) or even nodular fasciitis.33

Heterologous Biphasic Sarcomatoid Carcinoma

Other biphasic sarcomatoid neoplasms differ from the descriptions just given, in regard to their content of focal myogenous, vasogenic, chondro-osseous, or lipogenic differentiation.59 Thus, they are analogous to the heterologous form of malignant mixed müllerian tumors of the uterus, ovaries, and other female genital sites.60,61 Those neoplasms may exhibit microscopic foci that simulate embryonal or adult-type pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma, which contain proliferations of closely apposed compact round cells with a slightly myxoid background, or large “strap” cells with cytoplasmic eosinophilia and cross-striations, respectively14–16,33,34,46,52 (Fig. 14-6). Other heterologous SCs contain components that closely imitate the histologic features of osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma.23,34 In light of this information, it is easy to understand why lesions with such microscopic features were believed to be carcinosarcomas in the past and are still so designated by some observers today. The obviously carcinomatous elements in these lesions usually take the form of squamous carcinoma, but lesions with glandular or neuroendocrine differentiation have also been reported.14,54,55 Transitional zones between obvious epithelial foci, nondescript sarcomatoid areas, and myosarcoma-like components are often evident.

With regard to the relationship between biologic behavior and histologic appearance, there is no difference in the clinical evolution of homologous and heterologous biphasic pulmonary SCs. A distinction is made between those lesions only to reflect their synonymity with sarcomatoid epithelial tumors in other body sites.60,61

Monophasic Sarcomatoid Carcinomas

Some SCs display no conventional light microscopic evidence of epithelial differentiation whatsoever. A carcinomatous nature for these neoplasms is discerned only after immunohistochemical or ultrastructural evaluations have been done, but it is usually suspected beforehand because of the clinical and gross characteristics of the lesions.33

Most tumors in this category are constituted exclusively of cell populations like those in the sarcoma-like components of biphasic SCs. These potentially include foci that have an unremarkable spindle cell or pleomorphic image (Fig. 14-7) as well as areas imitating rhabdomyosarcoma, osteosarcoma, or other morphologic appearances that do not correspond to native tissues in the non-neoplastic lung. Because of the monomorphic nature of the tumor variants under discussion here, which lack any attributes of conventional lung carcinomas histologically, the corresponding diagnosis suggested by the World Health Organization criteria for pulmonary neoplasms62 (based only on hematoxylin and eosin stains and conventional histologic examination) would be that of a primary pulmonary sarcoma. The latter point has made the existence of monophasic SC of the lung somewhat contentious. Nevertheless, we have no doubt of its validity as a reproducible pathologic entity, and other authors appear to concur.35

Indeed, one might go so far as to state that virtually all malignant pulmonary tumors that are exclusively composed of heterologous (organ-inappropriate) elements—such as osteoblastic tissues63,64—are, in reality, monophasic SCs. That statement pertains even if no immunohistochemical evidence of epithelial differentiation can be found, because the ultimate biological evolution of such lesions is identical to that of conventional lung cancers.

Special Variants of Sarcomatoid Carcinoma of the Lung

Pulmonary Blastoma

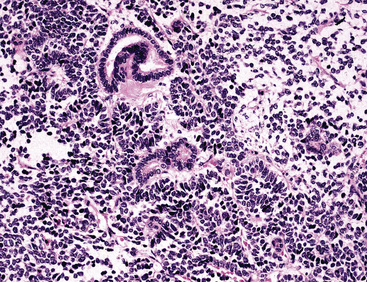

Since its initial description by Barnett and Barnard65 and a later discussion by Spencer,66 pulmonary blastoma (PB) has been regarded by some observers as the pulmonary counterpart of primitive childhood tumors of other organs.67–73 This view has been fostered in part by confusion of PB with pleuropulmonary blastoma (PPB; discussed subsequently), the latter of which is primarily seen in adolescent patients.74–80 PB is a biphasic neoplasm, containing a mixture of tubular epithelial cell profiles and compact groupings of nondescript bluntly fusiform cells with a blastema-like configuration39,74,77 (Fig. 14-8). These resemble the elements of renal Wilms tumors.81 On the other hand, PPB altogether lacks epithelial differentiation and may instead show divergent mesenchymal differentiation into myogenous or chondro-osseous tissues.77 Moreover, PB shows no particular disease associations, whereas PPB is linked in a familial fashion to a number of other malignant neoplasms and non-neoplastic disorders.79

If one carefully excludes examples of PPB from consideration, it becomes clear that PB is seen overwhelmingly in adults, and its clinical characteristics are superimposable on those of ordinary lung cancers and other pulmonary SCs. This realization allows one to more easily embrace an alternative view of the nature of PB that was advanced in the past by Souza and colleagues,82 Stackhouse and associates,14 and Millard,83 among others. Those authors held the opinion that PB is merely a special, usually peripheral form of pulmonary SC (carcinosarcoma), rather than a blastemal neoplasm that contains truly embryonal tissues. We also espouse the latter premise.

Returning to the particular microscopic attributes of PB, it should be noted that this tumor may demonstrate the same range of epithelial and mesenchymoid differentiation that is seen in other biphasic pulmonary SCs.39,69,84 The epithelial elements in PB resemble fetal pulmonary pseudoglands (a misnomer), composed of stratified columnar cells with glycogen-rich clear cytoplasm and high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios.69,84–86 Luminal mucin may be present in those cellular arrays, and squamous morules are sometimes also evident.69 Interestingly, “occult” neuroendocrine differentiation is a rather common finding in the epithelial components of PB, with potential histochemical argyrophilia and immunoreactivity for neuroendocrine markers.87,88 There is a significant sharing of microscopic features between classic PB and the tumor described as “pulmonary endodermal tumor resembling fetal lung” or alternatively as “well-differentiated adenocarcinoma simulating fetal lung” (Fig. 14-9). It differs in its relative lack of a malignant stromal component and more frequent synthesis of a particular oncofetal polypeptide—α-fetoprotein.39,85,87–90

The elements of PB showing mesenchymoid differentiation are, as stated earlier, usually nondescript morphologically and blastema-like or fibroblast-like. However, examples of this tumor have been documented in which heterologous rhabdomyoblastoid, leiomyosarcomatoid, or apparent chondro-osseous tissues were present.69,84 This observation serves to further solidify the linkage of PB to other sarcomatoid pulmonary carcinomas, as do reports of some tumors in which “typical” PB was admixed with homologous or heterologous biphasic SC, as described earlier.82,91–93

The clinical behavior of PB is difficult to determine with certainty, because of the aforementioned contamination of some series with cases of PPB. However, mortality figures of 30% to 70% have been reported, with death usually being due to distant metastases.67,69,84 Secondary deposits of PB may have a purely epithelial, purely mesenchymal-like, or biphasic appearance, as is true of other SCs.

Pseudoangiosarcomatous (Pseudovascular) Carcinoma

The authors have studied several lung tumors in which obvious squamous cell carcinoma was admixed with areas demonstrating interanastomosing channels mantled by anaplastic, plump, epithelioid cells, focally grouped into pseudopapillae. Because the open spaces in these areas contained erythrocytes and focally formed blood lakes, the histologic appearance was that of biphasic SC in which an angiosarcomatoid component was admixed with overt squamous carcinoma.94 (Fig. 14-10). These neoplasms are believed to represent the pulmonary counterparts of pseudovascular adenoid squamous cell carcinoma, as seen in the skin, breast, thyroid gland, and other organs.34,94–99 This is a tumor type that is known to simulate true angiosarcoma but lacks actual endothelial differentiation. Thus, pseudoangiosarcomatous carcinoma (PASC) would be an apt synonym.96

Primary pulmonary angiosarcoma is, comparatively, a very rare lesion, comprising only 10% of true sarcomas of the lung in one report from the Mayo Clinic.2 Mainly anecdotal reports of this tumor exist in the remaining literature, and not all of them satisfy rigorous diagnostic criteria.100–108 Metastases to the lung from angiosarcomas arising in extrapulmonary sites are much more common, including examples that have originated in the heart, great vessels, or extrathoracic viscera.100

Similar to reports on previously cited pseudovascular carcinomas in other body sites, two publications have specifically considered squamous cell carcinomas of the lung that imitated angiosarcomas. The first, by Banerjee and coworkers,96 showed that such tumors produced clinical symptoms and signs resembling those of ordinary types of lung cancer. They presented in the fifth to seventh decades of life; were associated with cigarette smoking, complaints of cough, weight loss, and dyspnea; and were visible on chest radiographs as well-defined central or peripheral parenchymal masses. In another series by Nappi and colleagues,94 the tumors were essentially identical microscopically to pseudovascular squamous carcinomas of the breast and skin. Important differences between PASCs and true pleuropulmonary angiosarcomas include an absence of atypical endothelial cells in stromal blood vessels surrounding the tumor mass in PASCs; less infiltrative growth through the interstitium of the lung; and, perhaps most importantly, the presence of small foci of morphologically obvious squamous cell carcinoma in most PASCs.94

Inflammatory Sarcomatoid Carcinoma

Much attention has been given to a group of space-occupying lesions in the lung that carry the popular but inaccurate designation of inflammatory pseudotumors (IPs).101–114 These proliferations may occur in children or adults and have been divided into fibrohistiocytic, plasma cell granulomatous, and focal organizing pneumonia types, based on their individual clinicopathological features. The nomenclature used for this group of lesions has been well summarized by Koss114 and Matsubara and associates.106 There is still some controversy over whether all such lesions are neoplastic, or whether some might be reactive in nature.115 However, the bulk of available information indicates that IPs are relatively innocuous clinical imitators of overtly malignant neoplasms.114 Occasional cases have been linked causally to specific infectious organisms,116,117 but the etiologic factors associated with most pulmonary IPs are uncertain.

In contrast, primary SC is generally regarded as a neoplasm that may simulate pleuropulmonary mesenchymal malignancies, and it is typically not mentioned in discussions on the pathologic differential diagnosis of IPs. This is so because SC usually demonstrates obvious cytologic anaplasia and lacks a significant component of inflammatory cells. Indeed, the morphologic distinction between IPs and all bronchogenic carcinomas (including SC) has been portrayed by some authors as an uncomplicated process.105,108 However, we have observed several examples of pulmonary SC that exhibited surprisingly bland morphologic appearances, and which, as a result, were separable from IP only by thorough study and adjunctive pathologic techniques. These have been designated as examples of inflammatory sarcomatoid carcinoma (ISC).118,119

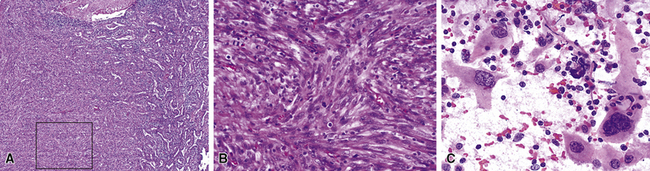

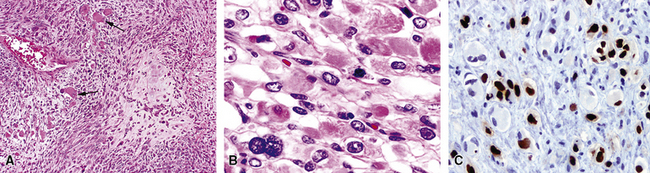

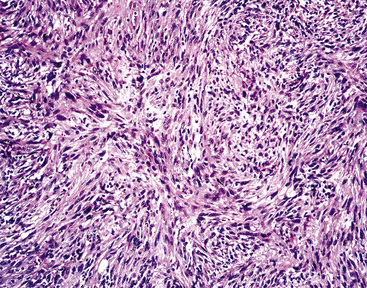

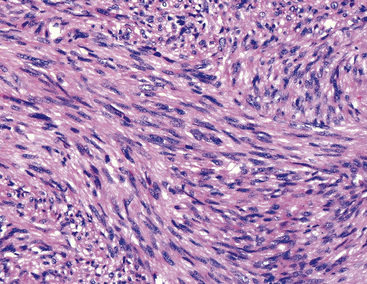

Examples of ISC are composed of variably densely apposed spindle cells with only modest pleomorphism, arranged haphazardly or in fascicular and storiform patterns. The stroma is at least partially myxoid in some cases and may be prominently so. The tumors demonstrate an irregular, spiculated interface with the surrounding lung. The adjacent parenchyma exhibits interstitial fibrosis, and small nodular infiltrates of mature lymphocytes are admixed with dense collagenous tissue at the periphery of ISCs (Fig. 14-11). Focally hyalinized, keloidal-type collagen is admixed with the tumor cells in the central portions of some of these tumors, with or without small foci of central necrosis. Vascular invasion and luminal obliteration by neoplastic cells may be apparent. Similarly, bronchial submucosal infiltration is another potential observation. ISCs do not contain appreciable stromal neutrophils, eosinophils, or xanthoma cells, but a moderate number of lymphocytes and plasma cells can be seen.

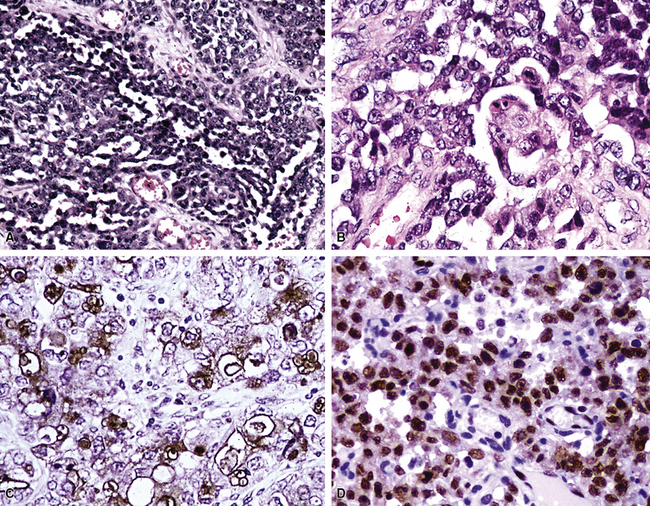

Cytologically, the nuclei of the tumor cells in ISCs are relatively uniform in size and spindle-shaped, with coarse chromatin and occasional small nucleoli (Fig. 14-12). Cytoplasm is moderate in amount and amphophilic. Generally, there are no more than 2 mitoses per 10 high-power fields (×400) on average, and pathologic division figures are absent. Thorough sampling of the tumor tissue in cases of ISC typically demonstrates minute foci of cohesive epithelioid cells, suggesting the diagnosis of squamous carcinoma on conventional histologic grounds. However, some ISCs lack such foci and are recognizable as carcinomas only with special pathologic evaluations (see Fig. 14-12B).118

Pleurotropic (Pseudomesotheliomatous) Sarcomatoid Carcinoma

Occasional examples of SC are distinctive not because of their histologic attributes but because of their macroscopic appearances. In particular, a small subset of these neoplasms arises in the very periphery of the pulmonary parenchyma and grows preferentially into the pleura that encases the lungs.120,121 This produces clinical symptoms and signs that are indistinguishable from those of malignant mesothelioma; hence, the names pleurotropic or pseudomesotheliomatous carcinoma.121,122 Moreover, the microscopic features of pleurotropic SC are basically superimposable with those of biphasic or sarcomatoid mesotheliomas.

Results of Adjunctive Pathologic Studies

Accounts of the electron microscopic and immunohistologic characteristics of pulmonary SC have not been altogether uniform. Some authors have preferred the view that such data in fact confirm the existence of true carcinosarcomas,123–125 whereas others have thought that this information instead supports the concept of a pathologic continuum that is predicated on carcinoma in pure form.15,17,38,126–130 We strongly prefer the second of these opinions.

It is true that the sarcoma-like elements in SC of the airways do not uniformly exhibit the ultrastructural presence of intercellular junctions and tonofibrils, or immunoreactivity for keratin or epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) in fusiform and pleomorphic tumor cells. In fact, these generic markers of epithelial differentiation may be seen only extremely focally in such neoplastic components, and we have even seen isolated examples in which cell membrane–based EMA reactivity was obvious, but keratin positivity was altogether absent. Humphrey and coworkers observed cytoplasmic tonofibrils or keratin positivity in the sarcomatoid elements of only three of eight pulmonary SCs.15 However, it should be noted that the latter study was performed with a single heteroantiserum to high-molecular-weight keratin, representing a relatively insensitive means of immunodetection. In our previously published experience with SCs of the respiratory tract,33 81% were ultrastructurally or immunohistochemically proven (with a mixture of monoclonal antikeratin antibodies [AE1/AE3/CAM5.2/MAK-6]) to be wholly epithelial in nature, and other authors have recorded similar findings at immunohistochemical and genetic levels of investigation.126–132

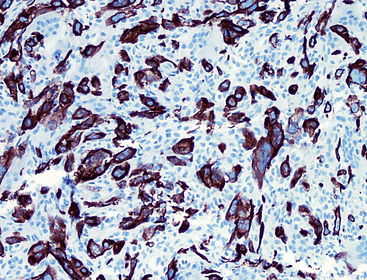

The fact that features of epithelial differentiation are present at all in the sarcomatoid elements of these neoplasms strongly supports the premise that respiratory tract SC is a basically carcinomatous lesion “in transition.”133 This concept has been well-accepted in reference to dedifferentiated sarcomas of the soft tissue, in which clonal evolution is thought to account for a change in the morphology as well as the immunophenotype of the progenitor lesion.134 Lessons learned in the latter sphere—as well as molecular biologic assessments of clonality in SCs135—have direct corollaries in the context under discussion here. We have observed the coexpression of vimentin (a “primordial” intermediate filament) in all examples of keratin-positive SC of the airways, and a minority of these lesions are additionally labeled for desmin (the intermediate filament of myogenous cells) and muscle-specific actin in the same cells that contain the other two filament proteins (Fig. 14-13).33 Collagen type IV is also seen surrounding individual tumor cells in most instances. Markers of neuroendocrine differentiation, such as chromogranin-A, CD57, and synaptophysin, likewise may be seen in selected lesions in their overtly epithelial components,53,55 and S100 protein is apparent in foci resembling chondroid tissue by conventional microscopy.4 In contrast, Friend leukemia-virus integration protein-1 (FLI-1) and CD31 are typically absent in PASC, whereas one or both of those endothelial determinants would be expected in true pleuropulmonary angiosarcomas.95,136

These accrued observations coincide with ultrastructural findings reported by Battifora in two cases of SC, which demonstrated the coincidence of desmosomes, tonofibrils, and collagen production in the same neoplastic cells, implying the presence of multilinear differentiation.137 Thus, SC can be viewed basically as an epithelial neoplasm with divergent mesenchymal differentiation, in which carcinoma cells acquire the potential to express a mesenchymal phenotype at light microscopic, ultrastructural, and immunohistologic levels. The pathogenetic bases for this peculiarity are currently unknown, but the practical deduction to be gleaned from this construct is that all SCs of the respiratory tract should be treated clinically as poorly differentiated carcinomas.

Wakely has reviewed the characteristics of pulmonary spindle cell tumors as seen in fine needle aspiration biopsy specimens138 (see Fig. 14-7). He concluded that adjunctive pathologic studies, such as those discussed above, were virtually mandatory before definitive diagnoses could be reached in that context.

Differential Diagnosis of Sarcomatoid Carcinoma

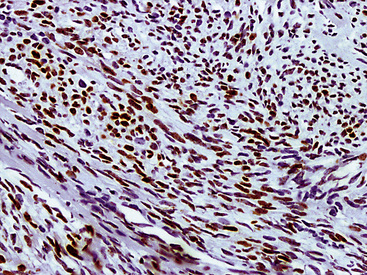

The differential diagnosis of SCs of the airways principally centers on the exclusion of true sarcomas, which are discussed later in this chapter. As a particular word of caution, it should be noted that synovial sarcoma (SS) and sarcomatoid mesothelioma may be very closely similar to SC as seen with the electron microscope or in immunophenotypic evaluations. The marked propensity for SS to affect children, adolescents, and young adults, its typical t(X;18) (p11.2;q11.2) cytogenetic aberration,139,140 and nuclear labeling for transducin-like enhancer [of Split]-1 (TLE1) protein141–144 (not seen in carcinomas) are crucial points in its distinction from SC of the upper airways. Of course, nuances of histologic appearances and radiographic characteristics are also valuable in this specific differential diagnostic setting. Similarly, roentgenologic findings are more helpful than morphologic observations in making the distinction between SC and spindle cell or biphasic mesothelioma. The ultrastructural profiles of the latter two lesions are again very similar,1,4,145 and, aside from selective reactivity for calretinin and podoplanin146 in mesotheliomas, the same comment applies to their immunophenotypes.

True Primary Sarcomas of the Lung

Kaposi Sarcoma

The natural history of KS is a sad testimony to the global impact of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). Before the 1980s, KS was a relatively rare neoplasm outside of Africa and the Mediterranean basin. Moreover, with relatively uncommon exceptions, this lesion was a cutaneous proliferation that uncommonly involved the viscera.147 However, today, with particular regard to the intrathoracic organs, KS is—in most large metropolitan areas of the world—the most common of all pulmonary sarcomas.148 Whereas initial presentation of this tumor in the bronchopulmonary tract was an almost-unknown phenomenon prior to the advent of AIDS, it is currently a well-recognized variation of the latter disease.149

Clinical Summary

In the context just mentioned, many patients with KS of the lung are homosexual men,150–156 but they also include other high-risk groups for AIDS such as intravenous drug abusers. Most individuals with KS generally have other symptoms and signs of AIDS, such as weight loss, fever, night sweats, fatigue, lymphadenopathy, and opportunistic infections. However, fever may be directly caused by KS in the lungs. There has been a case report of an AIDS patient with persistent pyrexia for which no source of infection was found but that finally resolved after radiation therapy.157 Cutaneous KS is usually detected early in its clinical evolution, but identical tumors of the bronchial mucosa and lung parenchyma typically have grown to a volume sufficient to produce symptoms and therefore are relatively advanced at the time of diagnosis.158 Presenting complaints specific to the neoplasm include dyspnea, stridor (when endobronchial lesions are present), cough, and hemoptysis, which may be massive.149

On bronchoscopic examination, nodular or flat bluish-red discolorations in the mucosa are seen, some of which may be actively bleeding. This bronchoscopic appearance is usually considered diagnostic, and endobronchial lesions are not generally biopsied. The diagnostic yield of transbronchial biopsies is usually low, and unless they are deep enough, KS of the lung will be missed because the mucosa itself is uninvolved.159 Open lung biopsies are more productive, but they are not absolutely sensitive.

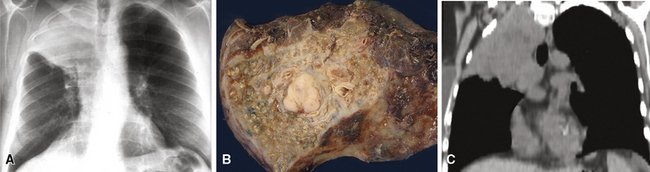

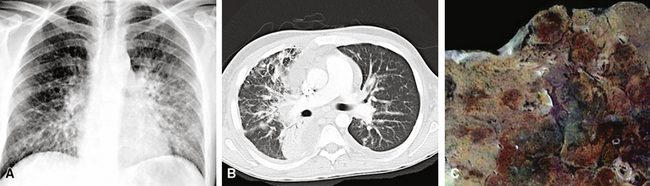

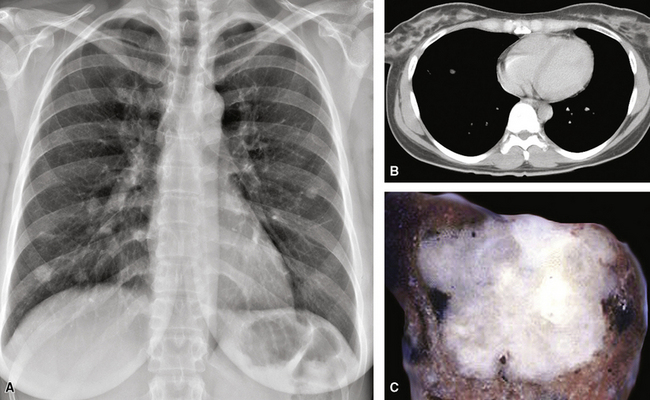

Radiographic findings on chest x-rays may be nonspecific, showing only ill-defined interstitial infiltrates (Fig. 14-14). An alveolar filling pattern is usually evident only if the patient has suffered hemoptysis and aspirated blood, but pleural effusions or pneumothorax may be seen in cases where the lesion involves the serosal surfaces as well as the lung parenchyma.160,161 Mediastinal adenopathy is not common, but, if it is present, this can be very helpful in separating KS from Pneumocystis jiroveci infection, because the latter does not cause adenopathy. Computed tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) generally provide no more information than chest radiography. In summary, the presence of bilateral pleural effusions and bilateral interstitial infiltrates with ill-defined nodularity is suggestive of pulmonary KS, especially in a patient with known tumor elsewhere.150,151

Pathologic Findings

As alluded to above, it is distinctly uncommon for the pathologist to be able to make a definitive diagnosis of KS of the lung on a transbronchial biopsy specimen. Usually, a wedge biopsy is necessary, as obtained via video-guided thoracoscopy or a limited thoracotomy.159 On gross examination, this type of specimen exhibits numerous hemangiomatoid or ecchymosis-like zones of bluish-red discoloration in the parenchyma, with ill-defined borders.

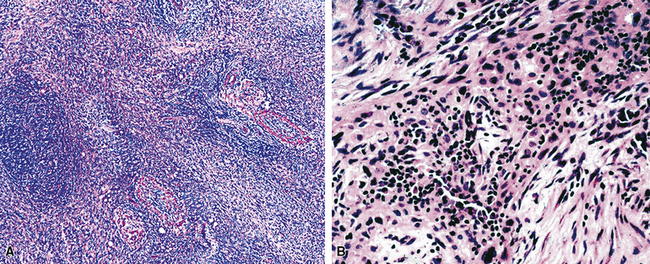

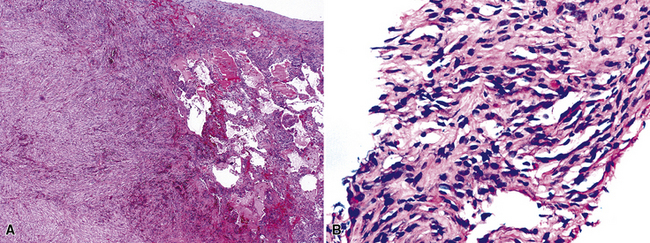

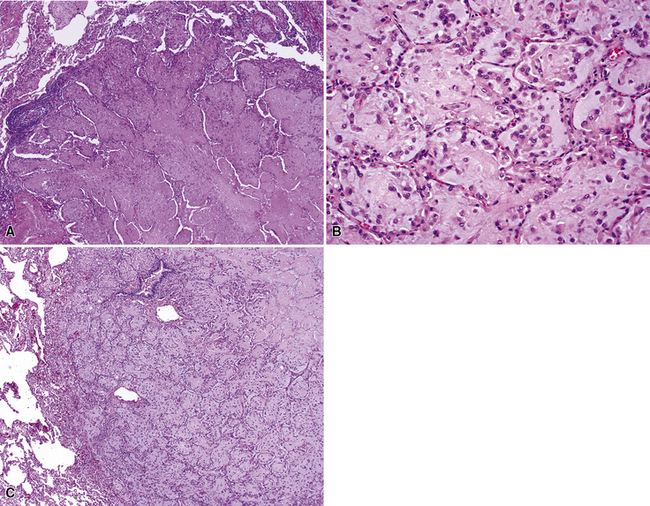

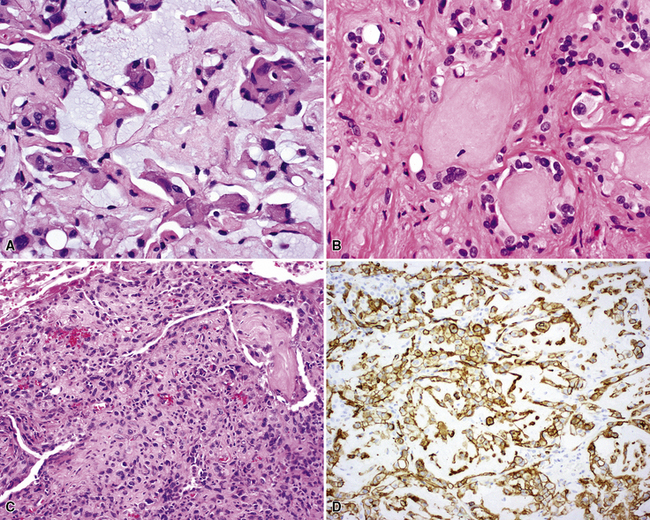

In the lung, KS shows a tendency to grow along pre-existing fibrous intrapulmonary septa, and it also concentrates around small tubular airways and blood vessels (Fig. 14-15). The tumor comprises a mixture of ectatic, thin-walled blood vessels that “dissect” or push through the pulmonary interstitial collagen, together with haphazardly arranged fascicles of spindle cells that show only modest nuclear atypia and may contain cytoplasmic vacuoles.149,159 Extravasated erythrocytes and hemosiderin pigment are common in and around the tumor masses (Fig. 14-16). Pleural KS “layers” itself over the submesothelial mantle of connective tissue, effacing the mesothelium itself in doing so.

The differential diagnosis of KS from vascular granulation tissue and other spindle cell proliferations in the lung is greatly enhanced by immunohistochemical analyses. KS is reactive for latent nuclear antigen-1 of human herpesvirus-8 in approximately 85% of cases162 (Fig. 14-17). It also labels for FLI-1163 and podoplanin.164

Therapy and Prognosis

Regardless of its occurrence in AIDS or in non–human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-related cases, the presence of KS in the lung is prognostically ominous. Virtually all patients with visceral disease die within 2 years, from infection if not from KS itself.148,154,156 Because of the multiplicity of KS, surgical resection is not a realistic option in the management of patients with this neoplasm. Chemotherapy is considered the treatment of choice, with a relatively good response rate and relatively rapid improvement within 2 to 4 weeks.25 Chemotherapy regimens in the few published therapeutic trials designed specifically for pulmonary KS have primarily included adriamycin, bleomycin, and vincristine.149,165–167 Gill and colleagues found an 85% response with combination chemotherapy in a group of 13 patients.166 Patients who benefited from this treatment included those who achieved at least partial responses. Complete response is defined by the following three criteria:

A partial response is characterized by the same three points, except that the degree of resolution is not total.165,166

Despite fairly good results with combination chemotherapy, patients with pulmonary KS do not show long survival. In the trial reported by Gill and colleagues, the median survival for responders was slightly but significantly longer than that of nonresponders (10 versus 6 months, respectively). However, considerable overlap between the two groups was present.166

Other more experimental (and inconclusive) approaches have included the administration of zidovudine, interferon, and other antiviral compounds.147,153,154 Radiotherapy may provide palliation of symptoms but is noncurative. The most important piece of data in prognosticating cases of KS of the lung is the serologic HIV status of the patient, inasmuch as AIDS is currently a uniformly lethal, albeit chronic, illness.

Fibrosarcoma

Primary fibrosarcoma of the lung (FSL), like its soft tissue counterpart, is defined as a fibroblastic spindle cell neoplasm without any evidence of specialized cellular differentiation. Although it has been cited in the past—along with leiomyosarcoma—as the most common primary pulmonary sarcoma,168 FSL was, and probably still is, overdiagnosed.169 Two separate studies from the Mayo Clinic cited two different time-dependent incidence figures for FSL. From 1950 to 1978, it constituted 50% of all primary pulmonary sarcomas170 but only 20% in the decade 1980 to 1990.171 As considered previously, it is our belief that the great majority of pulmonary “fibrosarcomas” are actually SCs. Only those tumors that have been subjected to rigorous and specialized pathologic examination should be accepted as bona fide examples of this rare sarcoma variant.

Clinical Summary

Guccion and Rosen studied 13 cases of FSL, which were divided into endobronchial and intrapulmonary types.168 This classification scheme was said to have clinical and prognostic importance. In conjunction with a review of 48 reported cases in the literature, the authors just cited found that the majority of endobronchial FSLs occurred in children and young adults, whereas parenchymal tumors predominated in middle-aged and elderly patients. In contrast, Pettinato and associates reported three parenchymal tumors in two newborns and a 6-month old infant.172 There was roughly an equal distribution by gender among endobronchial lesions; however, most intraparenchymal neoplasms occurred in men. All cases of endobronchial FSL in a series reported from the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP) had symptoms of cough, hemoptysis, or chest pain; some of the parenchymal cases did as well.168 Thoracic imaging studies of FSL usually show discrete, homogenous masses. However, one reported pulmonary fibrosarcoma simulated a bronchogenic cyst clinically and radiographically.173 Gladish and coworkers13 have observed that fibrosarcoma is much more likely to arise in the soft tissue of the chest wall and secondarily involve the lung than it is to show the converse of that relationship.

Pathologic Findings

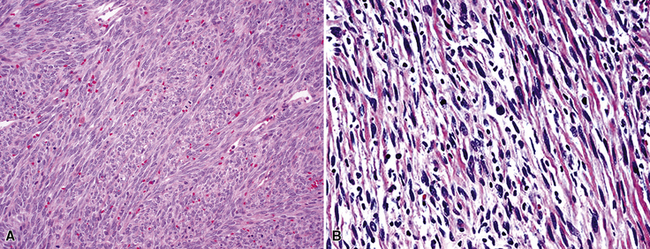

FSL is histologically identical to its soft tissue counterparts and characteristically shows sheets and intertwining fascicles of spindle-shaped cells with a typical interdigitating growth pattern and discernible stromal collagenogenesis (Fig. 14-18). The tumor cells contain oval to elongated, hyperchromatic nuclei, and scant amphophilic cytoplasm with ill-defined cellular borders. In addition, some areas may have a slightly epithelioid appearance, in which the tumor cells are more ovoid than spindled, and others may show significant pleomorphism that merges with the image of MFH (Fig. 14-19). Mitotic activity is variable.

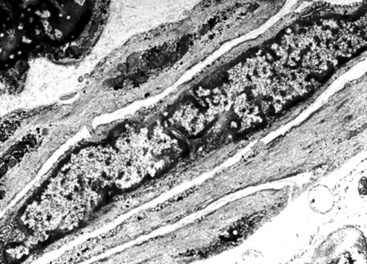

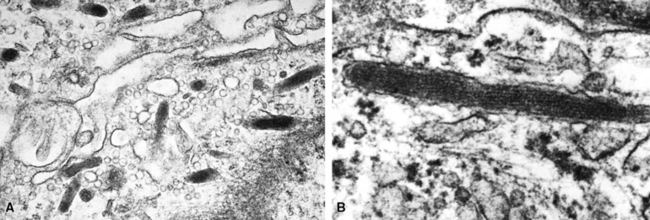

Electron microscopic and immunohistochemical studies are required to confirm the fibroblastic nature of these neoplasms. The tumor cells in FSL are characterized by abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum and free ribosomes, as well as the production of extracellular collagen fibers that may be aligned at right angles to the tumor cell membranes. There should be no detectable myofilaments, pericellular basal lamina, or intercellular junctions in lesions thought to represent FSL. Because there are no specific immunologic markers for fibroblasts, the diagnosis of fibrosarcoma is one of ultimate immunohistologic exclusion. Tumor cells in FSL generally stain only for vimentin, a primitive intermediate filament protein, and they lack all epithelial, myogenous, neural, and endothelial markers.172,174,175

Therapy and Prognosis

Although resection is the treatment of choice, many surgically treated fibrosarcomas of the lungs do recur, and survival after this event is short, with patient fatality usually occurring within 2 years.168 Three cases seen at the Mayo Clinic between 1980 and 1990 occurred in young women whose lesions all recurred within 15 months following surgical excision.171 In contrast, primary bronchopulmonary fibrosarcomas in children appear to have a relatively favorable prognosis and behave only as low-grade malignancies.172,173 The five patients with pediatric FSL reported by Pettinato and colleagues all had complete surgical removal of their tumors, and four were disease-free after 4 to 9 years. The fifth case in that series had insignificant follow-up.172 The efficacy of adjunctive chemotherapy and irradiation has not yet been proven.

Primary Pulmonary Hyalinizing Spindle Cell Tumor with Giant Rosettes

A rare lesion that is probably biologically related to FSL is one called hyalinizing spindle cell tumor with giant rosettes (HSCT). This entity was originally documented as a low-grade sarcoma in the deep soft tissues of adults,176 but at least two cases have been reported as primary pulmonary examples.177,178 HSCT has a distinctive morphologic appearance, featuring the multifocal presence of large rosette-like structures amid a bland spindle cell proliferation (Fig. 14-20). The lesion has infiltrative borders, with no necrosis and only limited mitotic activity.

HSCT has a partial kinship with Evans tumor (low-grade fibromyxoid sarcoma)179 of soft tissue, on behavioral, morphologic, and cytogenetic grounds. Both of those tumors manifest a t(7;16) (q33;p11) chromosomal translocation, producing fusion of the FUS and CREB3L2 genes.178 Unlike FSL, HSCT demonstrates some immunophenotypic variability, often labeling for alpha-isoform actin in its spindle cell population. The cells in the giant rosettes may manifest immunoreactivity for S100 protein and CD45RO,176 the latter of which is more typically a hematopoietic determinant. The precise biologic potential of HSCT in the lung is uncertain, because of the anecdotal nature of reported cases.

Primary Pulmonary Leiomyosarcoma

The most common anatomic locations for leiomyosarcomas in general are the uterus, gastrointestinal tract, and soft tissue, in order of relative frequency. The extremely uncommon primary pulmonary leiomyosarcoma (PPLMS) presumably originates from bronchial or pulmonary vascular smooth muscle. Only three cases of leiomyosarcoma were found among roughly 10,000 primary malignancies of the lung at one large American medical center between 1980 and 1990.171 Because secondary pulmonary involvement by malignant smooth muscle tumors is a relatively frequent event, the diagnosis of PPLMS absolutely requires exclusion of an occult extrathoracic neoplasm presenting with a single “herald” metastasis to the lung.

Clinical Summary

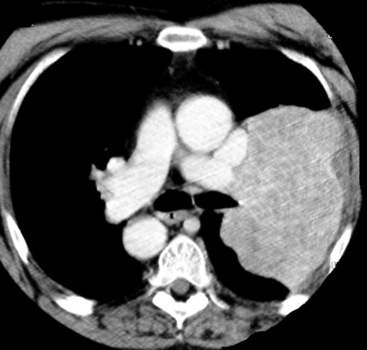

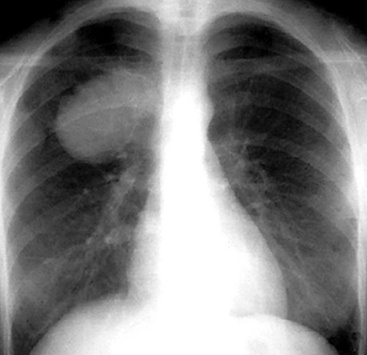

A series of 19 PPLMSs seen at the AFIP was divided into those neoplasms that were predominantly endobronchial and others that were intraparenchymal, in analogy to pulmonary fibrosarcomas.168 The majority of these tumors in children are endobronchial in nature,180,181 whereas those in adults are not. In contrast to leiomyosarcomas of the soft tissue, which occur most commonly in women, patients in the aforementioned report from the AFIP were almost exclusively men. However, another survey that reviewed 92 cases of PPLMS in the literature found a male-to-female ratio of 2.5, suggesting that the paramilitary study just cited was biased demographically by its affiliation with the armed services.182 In contrast to carcinoma of the lung, leiomyosarcoma is not associated with cigarette smoking or other potential inhalant carcinogens. Most patients with PPLMS (particularly its endobronchial form) are symptomatic, often complaining of cough, hemoptysis, or chest pain. However, intraparenchymal lesions may be discovered incidentally on chest radiographs. Roentgenographically, PPLMS usually takes the form of a discrete mass (Fig. 14-21), sometimes with cavitation or cyst formation that is best seen by CT of the thorax.168,183,184

Pathologic Findings

Parenchymal tumors range from 3 to 15 cm in maximum dimension. They are well circumscribed, white to yellowish tan, and variably firm. Cut surfaces of these neoplasms commonly show hemorrhagic and necrotic areas. Endobronchial tumors are often smaller than the intraparenchymal lesions, presumably because of confinement by the bronchial walls.185

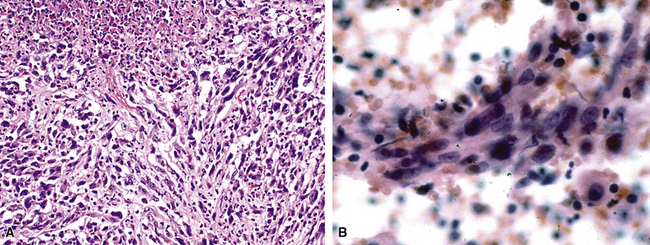

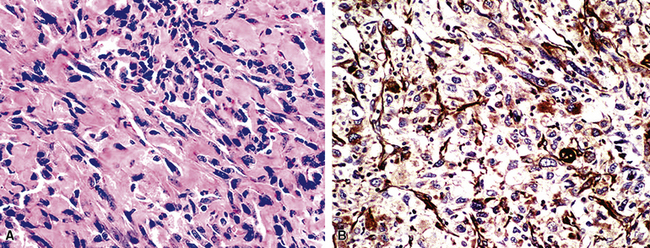

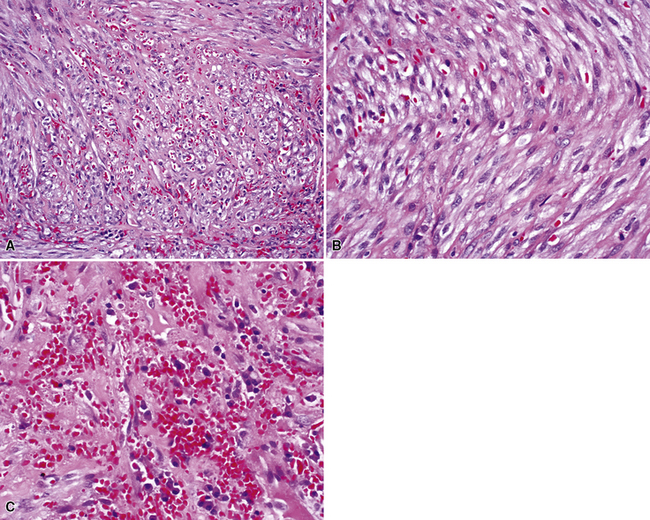

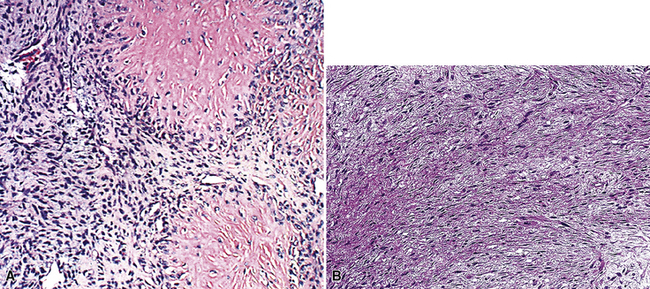

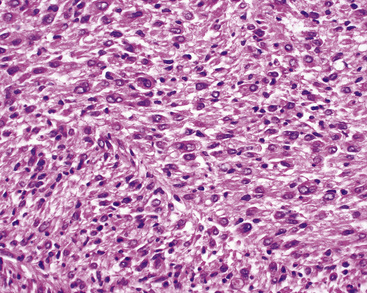

Microscopy discloses histologic features that mirror those of leiomyosarcomas elsewhere in the body. On low-power magnification, there are interlacing fascicles of spindled cells arranged haphazardly, yielding a “whorled” appearance (Fig. 14-22). The neoplastic cells have cigar-shaped nuclei with blunt ends, a moderate amount of cytoplasm, and indistinct cell borders (Fig. 14-23). Fascicles cut in cross section demonstrate characteristic intracellular perinuclear lucencies.185–188 Prominent myxoid stromal change may be observed.189

The differential diagnosis of PPLMS includes fibrosarcoma and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, as well as SC. Electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry are again helpful in confirming the smooth muscle nature of a spindle cell neoplasm.187 Ultrastructural features of leiomyogenous differentiation include cytoplasmic dense bodies punctuating skeins of thin filaments, subplasmalemmal dense plaques, plasmalemmal pinocytotic vesicles, and pericellular basal lamina (Fig. 14-24). Immunoreactivity for desmin, muscle-specific actin, calponin, caldesmon, or smooth muscle actin is also characteristic of the tumor cells in PPLMS.190

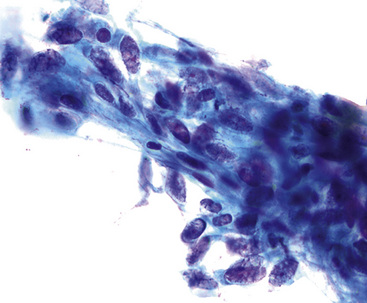

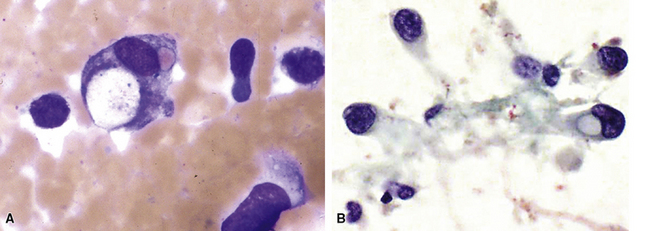

Transthoracic fine needle aspiration of possible PPLMS can be attempted if the lesion is large and peripherally located. The cytologic preparations from that procedure typically show a dyshesive population of relatively monotonous spindle cells, with blunt-ended fusiform nuclei. Mitotic figures and nuclear pleomorphism are variably seen; some lesions also may exhibit a more epithelioid cytologic image191–193 (Fig. 14-25).

Therapy and Prognosis

The natural history of PPLMS and its responses to various therapeutic regimens are difficult to predict because of the rarity of this neoplasm. However, there is generally a consensus that surgical resection is the treatment of choice182,185–187 and that it produces a survival rate of 45% to 50% at 5 years. Survival for as long as 15 to 30 years has been documented in PPLMS cases.168,170 However, pulmonary leiomyosarcomas appear to be relatively resistant to irradiation and chemotherapy.182,188 Various prognostic variables have been discussed in connection with these lesions.168,170 Endobronchial tumors are thought to be less aggressive than parenchymal neoplasms, largely because the former tend to be smaller and are diagnosed earlier. It follows, therefore, that tumor size is an important indicator of biologic behavior for all pulmonary leiomyosarcomas. The scope of mitotic activity may affect prognosis as well. In an AFIP series on PPLMS, a mitotic rate of 8 or less per 10 high-power fields was associated with infrequent metastasis and a generally favorable clinical outcome.168

Epithelioid Hemangioendothelioma

In 1975, Dail and Liebow reported the first cases of an unusual pulmonary neoplasm that they termed intravascular bronchioloalveolar tumor (IVBAT). This name reflected their original hypothesis that the lesion in question was an epithelial tumor—specifically, a bronchioloalveolar carcinoma variant showing prominent vascular invasion.194,195 Four years thereafter, Corrin and associates alternatively proposed an endothelial origin for this tumor based on the results of ultrastructural studies.196 Subsequent evaluations by other authors have confirmed the vascular histogenesis of the IVBAT. Indeed, in 1982, Weiss and Enzinger described a series of soft tissue tumors that were histologically identical to IVBAT, and these authors were the first to use the term epithelioid hemangioendothelioma (EH) to emphasize their distinctively epithelioid (or histiocytoid) cytologic features.197 In addition to the lungs and soft tissues, EH also primarily occurs in the bone and liver.198

Clinical Summary

EH of the lung is a neoplasm that arises predominantly in female patients; women account for roughly 80% of all cases.195,199,200 It primarily occurs in young adults, with approximately 50% of affected individuals being younger than 40 years of age; only 10% are older than 50 years of age at diagnosis.198,201 Many affected persons are asymptomatic, and their tumors are detected incidentally on chest radiographs. Patients who have tumor-related complaints usually present with pleuritic pain, dyspnea, and cough. Case reports have also documented alveolar hemorrhage as a presenting sign of pulmonary EH,202,203 and it may simulate thromboembolic disease symptomatically as well.204 Chest radiographs commonly show numerous, small nodular lesions throughout both lung fields (Fig. 14-26). Therefore, EH enters the roentgenographic differential diagnosis of multiple pulmonary nodules in asymptomatic young women, together with metastatic germ cell tumors, chondroid pulmonary hamartomas, multiple arteriovenous malformations of the lung, deposits of “benign metastasizing leiomyoma,” and malignant lymphoma.205

Pathologic Findings

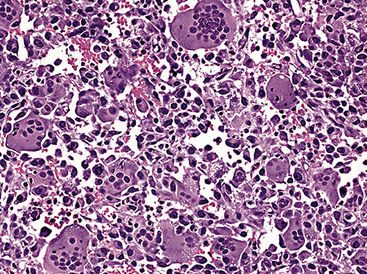

The pathologic diagnosis of EH is almost always made by open lung biopsy, inasmuch as transbronchial biopsy is usually ineffectual because of sampling constraints. Most nodules of EH are discrete and usually measure less than 2 cm. They are grayish-white to tan and have a chondroid macroscopic consistency. More nodules are typically seen on histologic examination than are apparent grossly. Microscopically, EH is typified by multiple oval or round nodules with hypocellular, sclerotic, or necrotic centers195,199 (Fig. 14-27). These are surrounded by rims of viable, more cellular tissue that is associated with a myxohyaline fibrous stroma; exceptionally, metaplastic bone formation may be apparent.206 The neoplastic cell population is composed of plump, epithelioid cells, which are the histologic hallmark of EH (Fig. 14-28). They have centrally located, round-to-oval nuclei, with ample amounts of eosinophilic cytoplasm. Often, intracytoplasmic vacuoles are evident, which should raise the possibility of endothelial differentiation on light microscopy. Saqi and colleagues have described “rhabdoid” cellular differentiation in EH as well.207

Ultrastructural and immunohistochemical evaluation can be of great assistance in confirming the endothelial origin of EH.196,198,208–211 Briefly, ultrastructural features of this tumor include cytoplasmic vacuoles, Weibel-Palade bodies (Fig. 14-29), cell membranous pinocytotic vesicles, and pericellular basal lamina.210 Histochemical and immunologic markers of endothelial differentiation—such as Ulex europaeus I lectin, anti-CD31, anti-FLI-1, and anti-CD34—are helpful in labeling the neoplastic cells in virtually all examples of EH.206,212 Weinreb and coworkers have also described labeling for CD10 in a majority of EH cases.213

Fine needle aspiration biopsy of EH yields a loosely cohesive population of epithelioid cells that may be binucleated or multinucleated. Variably sized cytoplasmic vacuoles are demonstrable in a proportion of the tumor cells (Fig. 14-30).214

Therapy and Prognosis

Surgery is usually not feasible as effective treatment for EH because of its tendency to show intrapulmonary multicentricity. Unfortunately, irradiation and chemotherapy likewise have been of little benefit.195,199 Nevertheless, EH is generally an indolent neoplasm that is classified as a borderline malignancy. It is associated with a protracted clinical course and potential survival of several years after diagnosis.208 Most patients do eventually succumb to the tumor and die of respiratory failure secondary to progressive parenchymal replacement; in one series reported by Einsfelder and Kuhnen, 36% of patients were dead or likely to die of their tumors after 52 months’ follow-up.206 Adverse prognostic factors that predict a more rapid decline in pulmonary function include prominent symptoms at the time of presentation; radiographic demonstration of extensive intravascular, endobronchial, or pleural spread of the tumor;195 and the presence of fusiform tumor cells.200

A particularly vexing clinical problem is represented by those patients who have EH synchronously in several organs, including the lungs. In such cases, one is never certain whether tumor multifocality or metastasis is operative. Pragmatically, each involved organ is usually treated as if it harbors an independent primary tumor in this scenario.215

The general predilection of EH for women, a reported association of primary hepatic EH with oral contraceptives, and the lack of effective therapy for this tumor have prompted some investigators to explore the possibility of treatment involving hormonal modulation. These tumors have been examined for possible expression of estrogen and progesterone receptor proteins as well as other estradiol-binding moieties. Ohori and colleagues analyzed five cases of pulmonary EH for steroid hormone receptors by immunohistochemical methods, using paraffin-embedded material.216 Only one case showed apparent binding of estradiol. Our own unpublished experience with the immunohistologic characteristics of pulmonary EH has disclosed no reactivity with monoclonal antibodies against estrogen and progesterone receptor proteins. Thus, we believe that hormonal therapies are unlikely to produce significant results in this setting.

Hemangiopericytoma and Intrapulmonary Solitary Fibrous Tumor

As first described in 1942 by Stout and Murray,217 hemangiopericytoma (HPC) is an uncommon, potentially malignant neoplasm that shows apparent differentiation toward the phenotype of pericytes. These are cells with long cytoplasmic processes that surround capillaries and serve a vasoregulatory function. HPC occurs most commonly in the deep muscles of the thigh, the pelvic fossa, and the retroperitoneum. However, 5% to 10% of all hemangiopericytomas are said to present as primary pulmonary tumors.185,218 It must be remembered that the lungs and the bones are the anatomic sites that most frequently harbor metastases of HPC,219 and therefore a primary extrapulmonary tumor must be excluded before a diagnosis of a primary HPC can be rendered safely.

It should also be understood that the currently recommended classification scheme for mesenchymal neoplasms has merged HPC with solitary fibrous tumor (SFT).220,221 Hence, for all intents and purposes, the two entities are considered to be closely related if not identical, and the abbreviation of HPC-SFT will be used in reference to that tumor group.

Clinical Summary

Pulmonary HPC-SFT affects men and women equally, and most commonly arises in middle adulthood. The peak incidence of this lesion is in the fifth decade of life, although individuals as young as 4 years of age and as old as 73 years of age have been reported.222,223 Some tumors are detected incidentally on radiographic studies without causing pulmonary symptoms; 6 of 18 cases in one series fit this scenario.224 Alternatively, presenting symptoms may include hemoptysis, chest pain, cough, and dyspnea, and, more rarely, pulmonary osteoarthropathy.224

Various radiographic imaging studies have been used in studying this neoplasm. Although angiography has usually not been performed, vascular contrast studies of HPC-SFT generally show a characteristic intralesional “blush.”225 No other pathognomonic features are evident in chest x-rays, CT scans, and MRIs of the lung.223,226 Plain film x-rays typically show a discrete, homogeneously dense mass with lobulated contours. On CT images, however, HPC-SFT is heterogeneous. Central low-density areas are evident that correspond to necrotic foci, and an apparent capsule may be seen at the interface with surrounding lung parenchyma. MRIs also show intratumoral heterogeneity with respect to tissue density and are apparently more sensitive in depicting intralesional hemorrhage. These images were found to be the most useful in delineating the potential plane of surgical separation between an HPC-SFT and surrounding soft tissue in one report.227 In summary, a radiologic diagnosis of pulmonary HPC-SFT may be suspected in a middle-aged person lacking pulmonary symptoms, but whose radiographic imaging studies reveal a large, lobulated, sharply marginated, variably dense mass (Fig. 14-31) that does not cause compression atelectasis.226

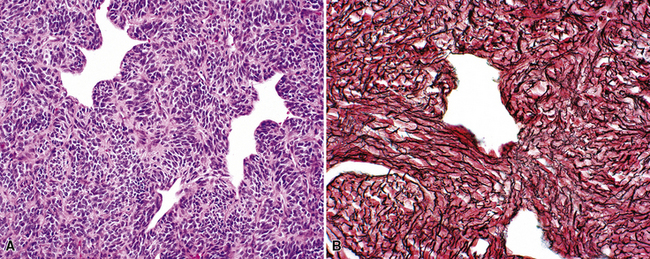

Pathologic Findings

HPC-SFTs of the lung can attain large sizes, and lesions measuring up to 18 cm have been documented. The typical gross appearance of this tumor is that of a well-circumscribed, yellow to tan-brown mass with a pseudocapsule, as well as areas of internal necrosis and hemorrhage. Histologic sections typically show a relatively monomorphous cellular proliferation surrounding thin-walled, anastomosing vascular channels lined by a single endothelial layer. These blood vessels often (but not always) assume gaping, “staghorn,” or “antler-like” configurations (Figs. 14-32 and 14-33). The population of neoplastic cells is uniform, with oval compact nuclei and ill-defined cytoplasm.185 Mitotic activity and areas of necrosis and hemorrhage are noted frequently. Vascular invasion of large pulmonary vessels, however, is uncommon. With regard to the latter features, some pathologists have, in the past, rendered a diagnosis of benign hemangiopericytoma if necrosis, hemorrhage, and mitoses were absent. In our view, this approach is highly inadvisable. We have seen cases of pulmonary HPC-SFT with exceedingly bland histologic profiles in which metastasis nonetheless supervened. Accordingly, it is advised that each report on this tumor should carry the statement that HPC-SFT is at least potentially malignant behaviorally.219,224

Pulmonary HPC-SFT has sometimes been overdiagnosed because other neoplasms may show foci that resemble the former lesion. In this regard, it is notable that in their seminal report, Stout and Murray admonished others to make the diagnosis of hemangiopericytoma by ultimate exclusion.217 The histologic differential diagnosis includes SC, SS, fibrous histiocytomas, leiomyosarcoma, and mesenchymal chondrosarcoma.219 Distinctions among these neoplasms are best made by ancillary studies.

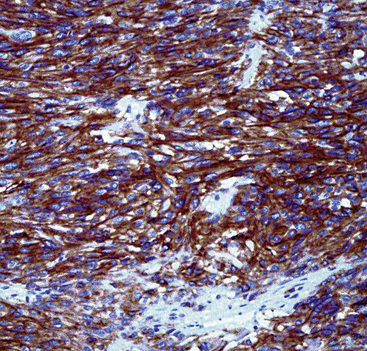

Electron microscopy can confirm the pericytic nature of HPC through the demonstration of polygonal cells with cytoplasmic processes, pinocytotic vesicles, basal lamina, and a paucity of other organelles.174,219 HPC-SFT is a neoplasm that demonstrates a relatively restricted group of immunoreactants; these include vimentin, collagen type IV, CD34, CD99, CD57, and bcl-2 protein54,228 (Fig. 14-34). Endothelial stains such as Ulex europaeus I, CD31, and FLI-1 highlight the lining of intralesional vascular spaces but do not label the surrounding tumor cells. Silver impregnation techniques highlight a complex reticulin matrix with individual cell investment.

Therapy and Prognosis

As in the management of soft tissue HPC-SFT, complete surgical excision is the mainstay of therapy for primary pulmonary tumors of this type. However, it is known that intraoperative rupture of pulmonary HPC-SFT may occur (especially those tumors that are adherent to the chest wall). As expected, this complication results in early local recurrence, as reported by Van Damme and associates, and should therefore be avoided at all costs.223 Chemotherapy and irradiation have not been shown to be consistently effective adjuvant modalities, but they may have some role to play in management.229,230 A study by Jha and coworkers on the general role of radiation therapy in treating HPC-SFT showed that postoperative irradiation was useful for local tumor control, salvage therapy after local recurrence, and palliation.231 Tumors less than 5 cm in maximum dimension exhibit a better response than those that are larger than 10 cm.232

As mentioned above, hemangiopericytomas in general are well known for their unpredictable biologic behavior. Postoperative survival has ranged from 10 weeks to 18 years.223,232 Even with apparently complete surgical resection, HPC-SFT recurs locally within 2 years in approximately 50% of cases,224,227,233 and later recurrences are seen as well; distant metastasis, however, is uncommon.228

Clinical and histologic features that have been cited as prognostically useful219,222,227 include the presence of symptoms at presentation, mitotic activity of four or more mitoses per 10 high-power microscopic fields, spontaneous tumor necrosis, vascular invasion, and tumor size greater than 5 cm. In one series, metastases were seen in one third of tumors that measured greater than 5 cm, and in two thirds of those greater than 10 cm.222 However, Yousem and Hochholzer did not find any single histologic or clinical feature that was statistically significant in reliably predicting the clinical course of primary pulmonary HPC-SFT.224

Malignant Fibrous Histiocytoma

MFH (now commonly called pleomorphic sarcoma, not further specified) is a common, extensively studied soft tissue sarcoma of older adults that develops most frequently in the extremities and the retroperitoneum. In a series of 200 cases by Weiss and Enzinger,234 the lungs were the most common site of metastases. Thus, exclusion of an occult soft tissue tumor is once again necessary before a diagnosis of primary pulmonary malignant fibrous histiocytoma (PPMFH) can be made. A review of Mayo Clinic cases found only four examples among 10,134 tumors arising in the lung.171 Currently, there are fewer than 75 reported cases of PPMFH in the English literature.234–245

Clinical Summary

In general, MFH is a neoplasm of patients who are in late middle age, with a median of 54 years. However, its occasional occurrence in children and young adults has also been reported.235,244 No consistent predilection for either gender is seen. Previous irradiation is a pathogenetic risk factor for tumors arising in soft tissue, and the literature similarly contains sporadic reports of PPMFH presenting in patients who have received radiation therapy previously. Clinical and radiographic features of this tumor are nonspecific, and a distinction from the much more common epithelial tumors of the lungs absolutely requires tissue examination. The majority of patients present with symptoms of cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, or dyspnea. Chest x-rays generally show a solitary mass with a nondescript appearance and a relatively homogeneous density on CT or MRI studies.243

Pathologic Findings

Most examples of PPMFH are intraparenchymal, but occasional endobronchial lesions have also been observed.235 There is apparently no predilection for any particular lobe of either lung. These tumors are usually large, ranging up to 25 cm in maximum dimension,246 with an average size of 6 to 7 cm. They are well circumscribed, lobular, and white-tan, and not uncommonly they contain central necrosis or cavitation on macroscopic examination.

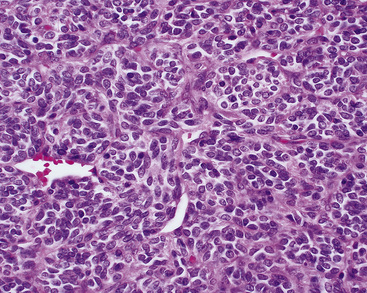

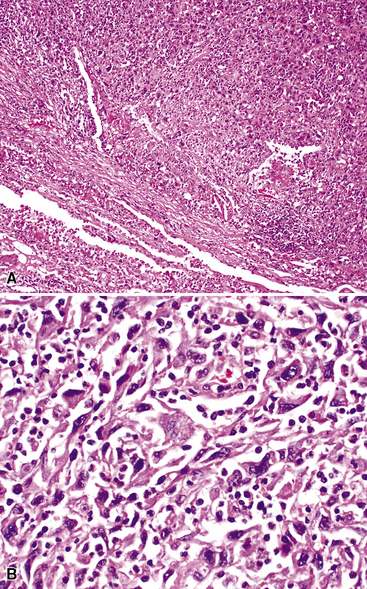

Histologically, PPMFH is characterized by fusiform and pleomorphic elements that are arranged in storiform, fascicular, or medullary patterns (Fig. 14-35). As the name “MFH” implies, this tumor was originally thought to be composed of malignant fibroblast-like and the histiocytoid cells; however, it now appears that there is little if any relationship between the neoplastic elements and true histiocytes. Fusiform tumor cells contain elongated nuclei and relatively scant cytoplasm, and the histiocytoid cells have round-to-oval nuclei with a moderate quantity of amphophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 14-36). A hallmark of most lesions in this category is the presence of large, bizarre, often multinucleated cells with irregular contours. Mitoses, including atypical forms, are easily found and number from 5 to 30 per 10 high-power microscopic fields.174

The differential diagnosis of PPMFH by light microscopy includes primary or secondary pleomorphic sarcomas (e.g., dedifferentiated leiomyosarcoma and pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma), metastatic malignant melanoma, and SC.13 Immunohistochemical and electron microscopic studies can be used to separate these pathologic entities.236–240,246 Ultrastructurally, PPMFH shows fibroblastic and histiocyte-like differentiation, with abundant rough endoplasmic reticulum, numerous lysosomes, and a variable number of small cytoplasmic lipid droplets. Desmosomes, tonofibrils, elongated cell processes, myogenous filament skeins, and cytoplasmic dense bodies are absent. PPMFH expresses vimentin but is devoid of other specialized markers of myogenous, neural, or epithelial differentiation on immunohistologic analyses.174

Therapy and Prognosis

The rarity of PPMFH again serves as an impediment to assessments of optimal treatment for this tumor. Surgical resection is currently the recommended treatment of choice, even if the lesion in question shows limited extrapulmonary spread to the intrathoracic great vessels or soft tissue.247 Adjunctive chemotherapy and irradiation have not proven to be effective in the few published cases of PPMFH in which these treatments have been used.235,245,246 In one series of 22 examples,235 7 of 15 patients who underwent radical surgical resection suffered relapses and died from metastatic disease. There was recurrence in the lungs and pleura, as well as metastasis to the liver and brain; almost all of these events occurred within 12 months of diagnosis. However, survival for as long as 5 to 10 years has been documented in a few patients with PPMFH.235,237

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree