It is unclear if clinician risk stratification has changed with time. The aim of this study was to assess the temporal change in the concordance between patient presenting risk and the intensity of evidence-based therapies received for non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes over a 9-year period. Data from 3,562 patients with non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes enrolled in the Australian and New Zealand population of the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE) from 1999 to 2007 were analyzed. Patients were stratified to risk groups on the basis of the GRACE risk score for in-hospital mortality. Main outcome measures included in-hospital use of widely accepted evidence-based medications, investigations, and procedures. Invasive management was consistently higher in low-risk patients than in intermediate- or high-risk patients (coronary angiography 66.7% vs 63.5% vs 35.3%, p <0.001; percutaneous coronary intervention 31.1% vs 22.0% vs 12.9%, p <0.001). Absolute rates of angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention in the high-risk group remained 24% and 15% lower compared to the low-risk group in the most recent time period (2005 to 2007). In-hospital use of thienopyridine, low–molecular weight heparin, and glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors showed a similar inverse relation with risk. Prescription of aspirin, β blockers, statins, and angiotensin receptor blockers was inversely related to risk before 2004, although this inverse relation was no longer present in the most recent time period (2005 to 2007). Only in-hospital use of unfractionated heparin showed use concordant with patient risk status. In conclusion, despite an overall increase in the uptake of evidence-based therapies, most investigations and treatments are not targeted on the basis of patient risk. Clinician risk stratification remains suboptimal compared to objective measures of patient risk.

During the past decade, practice guidelines have universally acknowledged the importance of risk stratification, with a current American College of Cardiology and American Heart Association class 1A recommendation for risk stratification in the setting of non–ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes (NSTEACS). Additionally, a number of risk stratification aids, including clinical pathways, diagnostic algorithms, and specific risk stratifications tools including risk scores, are now widely available. However, it is unclear if increased awareness of risk stratification or the wide availability of risk stratification tools has necessarily altered clinicians’ risk stratification behavior. We sought to evaluate this by analyzing practice patterns within the Australian and New Zealand population enrolled in the Global Registry of Acute Coronary Events (GRACE). We specifically sought to determine (1) whether the uptake of evidenced-based therapies observed over time was concordant with the level of patient risk and (2) whether this relation had changed over time to indicate a temporal change in clinicians’ risk stratification behavior. Australia and New Zealand are highly developed nations with advanced health care systems. Importantly, guidelines for acute coronary syndromes (ACS) have been widely disseminated in this population. Although the number of hospitals enrolled in this cohort was small, enrolling hospitals were all metropolitan hospitals, and most were teaching hospitals. More important, patient enrollment in this cohort spanned nearly a decade and thus represents an ideal population to assess temporal change in clinicians’ treatment practices.

Methods

Full details of the methods of GRACE have been published elsewhere. GRACE is designed to reflect an unbiased population of patients with ACS. Patients enrolled in the GRACE registry were ≥18 years of age, were alive at the time of presentation, and presented with symptoms suggestive of coronary ischemia. In addition to symptoms, patients were required to have electrocardiographic changes consistent with ACS, elevation of serum cardiac biomarkers of myocardial necrosis, or documented coronary artery disease. ACS precipitated by noncardiovascular co-morbidities, such as anemia or trauma, were excluded. To enroll an unselected population, the first 10 to 20 consecutive eligible patients were recruited from each site per month. Data were collected by trained coordinators using a standardized case report forms. Demographic characteristics, medical history, presenting symptoms, biochemical and electrocardiographic findings, treatment practices, and a variety of hospital outcome data were collected. Selected study outcomes were assessed 6 months after discharge. Standardized definitions for all patient-related variables and clinical diagnoses were used.

For this analysis, we limited our study to the Australian and New Zealand population enrolled in the GRACE registry from 1999 to 2007. We included all patients with discharge diagnoses of NSTEACS (non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and unstable angina) on the basis of previous published criteria. We included patients who directly presented to the hospital as well as patients transferred from outlying hospitals. The primary outcomes for this study were rates of in-hospital investigations and procedures (coronary angiography, percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI], coronary artery bypass surgery, echocardiography, and exercise stress testing), guideline-based in-hospital medication use (aspirin, thienopyridine, unfractionated heparin, low–molecular weight heparin, glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, β blockers, statins, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers), and referral to cardiac rehabilitation on discharge.

Our study cohort was derived from 11 metropolitan centers, of which 8 (73%) were teaching hospitals with onsite cardiac catheterization facilities. Five of 11 centers (45%) had onsite cardiac surgical facilities. At noninterventional and nonsurgical sites, it would be routine practice to transfer patients for angiography and revascularization (PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting). To account for these centers, our rates of coronary angiography, PCI, and coronary artery bypass grafting included patients if they were referred to other hospitals for the procedures or underwent the procedures as outpatients, provided these were booked from the index admissions. For all other investigation and medications, patients were considered only if they underwent the investigations or received the medications during the index admission.

Data are summarized as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD for normally distributed data. Otherwise, data are presented as medians and 25th and 75th percentiles. For evaluation of temporal trends, the enrollment period was divided into 3 yearly groups (1999 to 2001, 2002 to 2004, and 2005 to 2007). Patients were stratified according to their levels of risk at presentation (low, intermediate, and high risk) according to the GRACE risk score for in-hospital death using previously published cut-off values. Chi-square statistics were used to evaluate differences among risk groups for each year group. Furthermore, the temporal trend (increase or decrease) in the outcome variable across year groups for each risk category was evaluated. Trend analysis was performed using the double-sided Cochran-Armitage test or logistic regression. A p value <0.05 was used as a cutoff for statistical significance. The analysis was performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina). Data were >98% complete for all variables, with the exception of referral for cardiac rehabilitation, for which complete data are available only from 2000 onward. To account for possible changes in baseline risk, we calculated the average GRACE risk score for in-hospital death for each year of enrollment. Although there was a slight increase in baseline risk, this failed to reach statistical significance (p = 0.055).

Results

A total of 3,982 patients with discharge diagnoses of NSTEACS (2,098 with non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarctions, 1,794 with unstable angina) were enrolled in the Australian and New Zealand population of GRACE from 1999 to 2007. Of these, 330 had missing data for ≥1 of the components of the GRACE risk score for in hospital death and were excluded. The remaining 3,562 were included in the study. The population was stratified on the basis of the GRACE risk score for in-hospital mortality ( Table 1 ), and a gradient of risk characteristics was observed. Risk stratification on the basis of the GRACE risk score appropriately predicted in-hospital death, congestive heart failure, and renal failure ( Table 2 ) and death at 6 months. Presentation risk was not associated with risk for in-hospital stroke (p = 0.54) or major bleeding (p = 0.18).

| Variable | Patient Risk at Presentation | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Intermediate | High | ||

| n | 1,370 (38.5%) | 1,172 (32.9%) | 1,020 (28.6%) | 0.191 |

| Age (years) | 57.6 ± 10.4 | 69.8 ± 9.5 | 77.7 ± 8.2 | <0.001 |

| Men | 984 (71.8%) | 771 (65.8%) | 605 (59.4%) | <0.001 |

| Australian | 1,038 (75.7%) | 871 (74.3%) | 770 (75.5%) | 0.671 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Acute myocardial infraction | 481 (35.1%) | 515 (44.1%) | 493 (48.4%) | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 45 (3.3%) | 129 (11.1%) | 291 (28.9%) | <0.001 |

| Angina | 788 (57.7%) | 758 (65.1%) | 656 (64.7%) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 251 (18.3%) | 281 (24.0%) | 207 (20.3%) | 0.002 |

| PCI | 345 (25.2%) | 231 (19.8%) | 101 (9.1%) | <0.001 |

| Hypertension | 741 (54.3%) | 760 (65.1%) | 677 (66.6%) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 912 (66.7%) | 746 (63.8%) | 552 (54.5%) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes (type 1 or 2) | 336 (24.6%) | 323 (27.7%) | 334 (32.8%) | <0.001 |

| Renal impairment | 33 (2.4%) | 104 (8.9%) | 185 (18.2%) | <0.001 |

| Smoker (current or former) | 940 (68.7%) | 727 (62.3%) | 561 (55.0%) | <0.001 |

| Transient ischemic attack or stroke | 91 (6.7%) | 158 (13.6%) | 176 (17.4%) | <0.001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 77 (5.7%) | 148 (12.7%) | 156 (15.4%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 61 (4.5%) | 125 (10.7%) | 211 (20.8%) | <0.001 |

| Major bleeding | 24 (1.8%) | 31 (2.7%) | 36 (3.5%) | 0.026 |

| Prehospital medication use | ||||

| Aspirin | 747 (54.6%) | 673 (57.4%) | 579 (56.8%) | 0.313 |

| Clopidogrel | 102 (10.7%) | 99 (12.0%) | 64 (9.3%) | 0.227 |

| β blockers | 551 (40.3%) | 517 (44.3%) | 431 (42.5%) | 0.129 |

| Statins | 666 (48.8%) | 572 (49.1%) | 442 (43.5%) | 0.013 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs | 514 (38.3%) | 525 (45.9%) | 507 (50.8%) | <0.001 |

| Warfarin | 46 (3.4%) | 73 (6.3%) | 96 (9.5%) | <0.001 |

| Presentation characteristics | ||||

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 73.8 ± 15.7 | 76.4 ± 18.6 | 89.2 ± 27.3 | <0.001 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 150.8 ± 25.6 | 144.8 ± 25.9 | 138.0 ± 31.0 | <0.001 |

| Killip class >1 | 37 (2.7%) | 172 (14.7%) | 484 (47.5%) | <0.001 |

| Cardiac arrest at presentation | 0 (0%) | 3 (0.26%) | 23 (2.25%) | <0.001 |

| ST change | 115 (8.4%) | 297 (25.3%) | 569 (55.8%) | <0.001 |

| Elevated initial cardiac enzymes | 301 (21.9%) | 407 (34.7%) | 554 (54.3%) | <0.001 |

| Initial creatinine (mmol/L) | 84.0 ± 47.2 | 99.7 ± 59.4 | 129.7 ± 93.4 | <0.001 |

| In-Hospital Event | Low | Intermediate | High | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality | 0.3% | 0.6% | 6.7% | <0.001 |

| Heart failure | 2.2% | 6.6% | 24.4% | <0.001 |

| Stroke | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.4% | 0.537 |

| Major bleeding | 0.7% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 0.180 |

| Renal failure | 0.3% | 1.5% | 7.1% | <0.001 |

| 6-month mortality | 0.57 | 3.76 | 10.96 | <0.001 |

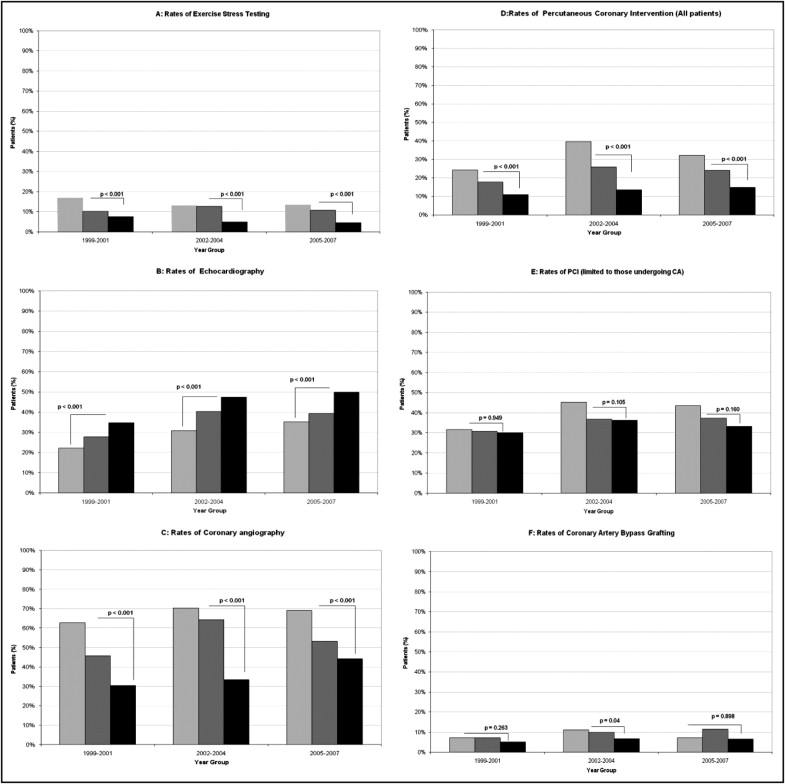

Changes in investigations and revascularization procedures over time stratified according to the baseline risk of the patients are shown in Figure 1 and listed in Table 3 . In-hospital referral for exercise stress testing was concordant with risk with the low-risk group consistently having the highest rates of exercise stress testing ( Figure 1 ). Overall, the rate of referral for exercise stress testing was low. Referral for echocardiography showed a temporal increase in the referral rate across all risk groups ( Figure 1 ). Referral was concordant with patient risk, with more high-risk patients than low-risk patients undergoing echocardiography.

| Variable | Presenting risk category | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Intermediate | High | ||||

| % Change | p Value for Trend | % Change | p Value for Trend | % Change | p Value for Trend | |

| Procedures | ||||||

| Exercise stress testing | −3.43% | 0.119 | 0.60% | 0.727 | −3.00% | 0.092 |

| Echocardiography | 13.1% | <0.001 | 11.4% | <0.001 | 15.0% | <0.001 |

| Coronary angiography | 6.2% | 0.047 | 7.6% | 0.013 | 13.7% | 0.001 |

| PCI (all) | 8.0% | 0.004 | 6.4% | 0.031 | 4.0% | 0.146 |

| PCI (catheterization+) | 11.9% | 0.003 | 6.7% | 0.188 | 3.2% | 0.635 |

| Coronary artery bypass grafting | 0.1% | 0.768 | 4.3% | 0.038 | 1.4% | 0.425 |

| Medications or referral to rehabilitation | ||||||

| Aspirin | −0.9% | 0.378 | −0.5% | 0.852 | 2.9% | 0.244 |

| Thienopyridines | 45.0% | <0.001 | 47.4% | <0.001 | 40.2% | <0.001 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors | 5.1% | 0.008 | 2.5% | 0.108 | 2.4% | 0.124 |

| Low–molecular weight heparin | −2.3% | 0.405 | 6.2% | 0.024 | 1.6% | 0.653 |

| Unfractionated heparin | −17.6% | <0.001 | −15.5% | <0.001 | −15.1% | <0.001 |

| β blockers | 7.3% | 0.002 | 9.8% | 0.001 | 12.4% | 0.000 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs | 28.4% | <0.001 | 17.9% | <0.001 | 15.9% | <0.001 |

| Statins | 15.2% | <0.001 | 24.4% | <0.001 | 29.1% | <0.001 |

| Referral to cardiac rehabilitation | 24.2% | <0.001 | 11.3% | <0.001 | 21.6% | <0.001 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree