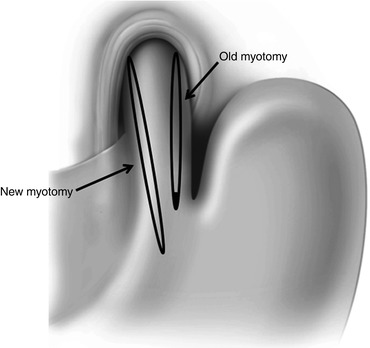

Fig. 17.1

30–40° separation of the myotomy edges

4.

Tight closure of the hiatus. Because sutures that narrow the hiatal opening may impair esophageal emptying, we do not advocate hiatal closure in the average patient with achalasia. The choice of antireflux procedure to be associated with the Heller myotomy (most commonly a Dor or a Toupet) should have no bearing on it. Indeed, when a Dor fundoplication is done, there is not even a need to dissect the posterior aspect of the GEJ, and the hiatus should remain undisturbed. When a Toupet fundoplication is used, the natural opening of the hiatus serves as a perfect platform to “fix” the right and the left side of the partial wrap. Hiatal closure should be considered only for the rare patient who has an associated large hiatal hernia; and in those patients, we recommend the hiatus be closed only partially to avoid persistence of dysphagia.

5.

Wrong type of fundoplication. A 360° fundoplication may create a mechanical obstruction because of the lack of peristalsis in patients with achalasia.

6.

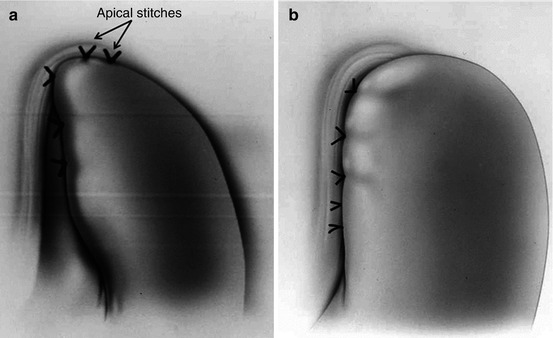

Wrong configuration of the fundoplication. Either an anterior or a posterior partial fundoplication may be a cause of persistent dysphagia. A Dor fundoplication (180° anterior) must be constructed with two rows of sutures only, one on the left and one on the right [9]. The left row should have three sutures, with the upper one incorporating the esophagus, the fundus of the stomach, and the left pillar of the crus. The second and the third stitches are placed between the fundus of the stomach and the left side of the esophageal wall. After folding the fundus over the exposed mucosa, three additional sutures are placed. The first one incorporates the fundus of the stomach, the esophagus, and the right pillar of the crus: the second and the third stitches should only incorporate the esophageal wall and the fundus. Too many stitches at this level will cause constriction of the GEJ (Fig. 17.2a, b). Patti et al. showed that problems with the construction of a Dor fundoplication could be a cause of both persistent and recurrent dysphagia [2]. Apical stitches and transection of the short gastric vessels are also important as they avoid tension on the fundoplication (Fig. 17.2a). A Toupet fundoplication (240° posterior) may also cause angulation of the esophagus (if it is not appropriately sized) and problems with esophageal emptying. The technical steps have been described elsewhere [11].

Fig. 17.2

Dor fundoplication. (a) Correct configuration. (b) Wrong configuration

Recurrent Dysphagia

Recurrent dysphagia is far more common than persistent dysphagia. These are patients who experience substantial relief for months or years after the initial Heller myotomy and then progressive dysphagia slowly develops. The specific cause of recurrent dysphagia is not always easy to elucidate as progression of disease, scarring in the area of the previous Heller, or rare conditions such as cancer may be causing it. Most common causes usually attributed to the development of recurrent dysphagia are:

1.

Scarring of the distal edge of the myotomy. When patients experience recurrent symptoms after a long symptom-free interval, scarring at the distal edge of the myotomy is the most common cause [2, 19, 20]. While studies to date have not identified specific factors that predict this problem, we believe that a longer myotomy and a wider separation of the edges of the myotomy at the time of initial operation should decrease the frequency of this problem [3, 6].

2.

Complete fundoplication. We have long maintained that a partial fundoplication is the procedure of choice in conjunction with a Heller myotomy as it takes into consideration the lack of esophageal peristalsis. Because both a Dor and a Toupet fundoplication are effective in controlling reflux in only 60–70 % of patients, some authors have proposed the use of a Nissen fundoplication which is a more effective antireflux procedure [21]. This approach however is associated with poor long-term results [22, 23]. For instance, Rebecchi et al. compared 71 patients who underwent a laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Dor fundoplication in 67 patients who had a Heller myotomy and a Nissen fundoplication [23]. After 10 years, dysphagia was present in 2.8 and 15 % of patients, respectively. Similar problems have been reported by others [22].

3.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Postoperative reflux is present in 50–60 % of patients when a myotomy alone is performed and in 30–40 % when a partial fundoplication is added. Abnormal reflux is considered a common cause of recurrent dysphagia. Csendes et al. showed that there is a progressive clinical deterioration of the initially good results over time and that this deterioration is mainly due to an increase in pathologic reflux and the development of short- or long-segment Barrett’s esophagus [24]. Unfortunately, most patients that develop pathologic reflux are asymptomatic [1]. It is therefore very important, particularly when operating on young patients, to perform an ambulatory pH monitoring after the operation [25]. If abnormal reflux is demonstrated, acid-reducing medications should be prescribed, and closer endoscopic follow-up performed.

4.

Esophageal cancer. Achalasia patients are at increased risk of developing squamous cell carcinoma. In addition, if pathologic reflux occurs after the myotomy, Barrett’s esophagus and adenocarcinoma can develop causing recurrent dysphagia [26]. Even though precise guidelines about endoscopic follow-up in achalasia patients have not been established, an upper endoscopy should be routinely performed every 3–5 years.

Diagnostic Evaluation

When patients complain of persistent or recurrent dysphagia, it is important to perform a complete work-up to try to identify the cause and site of obstruction in order to formulate a tailored treatment plan [27].

The first step should always be to review the entire history – in particular that which existed before the first operation – and to review, when possible the diagnostic tests performed before the initial operation. It is at this time that we have found, with distressing frequency, that some of these patients did not have achalasia to begin with. Once this process is complete, we like to review the report of the original operation. Often there are clues that explain the symptoms, such as the description of scar tissue due to prior treatment, failure of identifying the anatomic planes, or a short myotomy.

The symptomatic evaluation is the next step. It determines which symptoms are present and compares them to the symptoms present before the first operation. In addition, it distinguishes between persistent and recurrent dysphagia.

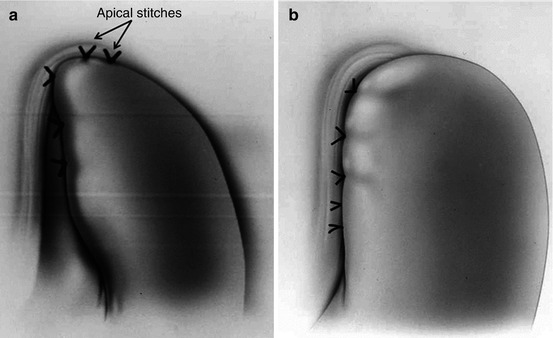

A barium swallow is probably the most useful test to determine the cause of the dysphagia. It identifies the area of obstruction; assesses the degree of esophageal dilatation, the emptying of the barium from the esophagus into the stomach; and reveals the overall shape of the esophagus. It might help distinguish between a short myotomy, a tight closure of the hiatus, and a constricting or malpositioned fundoplication (Fig. 17.3a, b). Loviscek et al. recently reported a series of patients with recurrent dysphagia after Heller myotomy who underwent redo surgery and was able to correlate the preoperative radiologic findings on barium swallow to the postoperative improvement in reflux symptoms. Patients with a straight esophagus (normal or dilated caliber) all had improved dysphagia after revisional surgery, whereas dysphagia improvement was less consistent if the esophagus was sigmoid in shape [27].

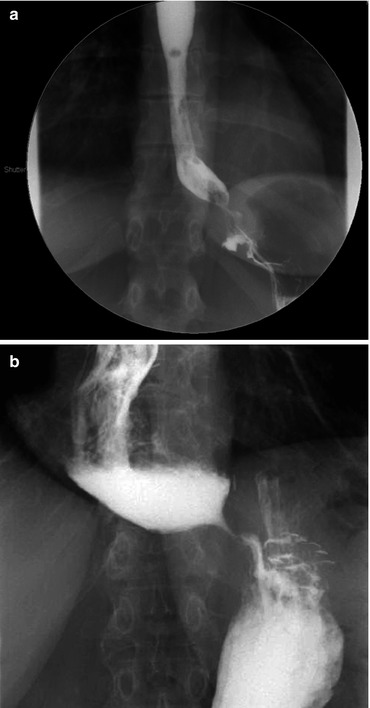

Fig. 17.3

Barium swallow. (a) A malpositioned Dor fundoplication impinges on the gastroesophageal junction creating a partial obstruction. (b) An incomplete myotomy resulting in persistent dysphagia

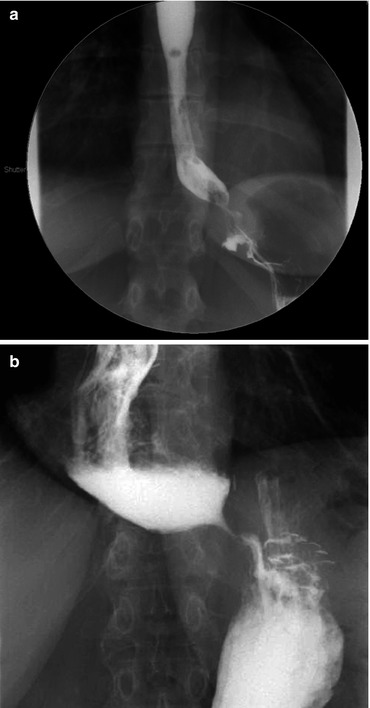

An upper endoscopy should be carried out in every patient. It shows if there is mucosal damage due to reflux, or Candida esophagitis due to slow emptying, and rules out the presence of cancer. Endoscopic evaluation can also reveal angulation of the distal esophagus due to a malpositioned or overly tight fundoplication (Fig. 17.4a, b).

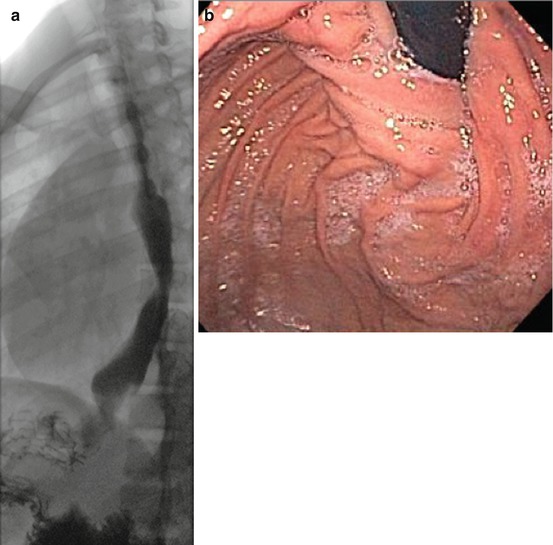

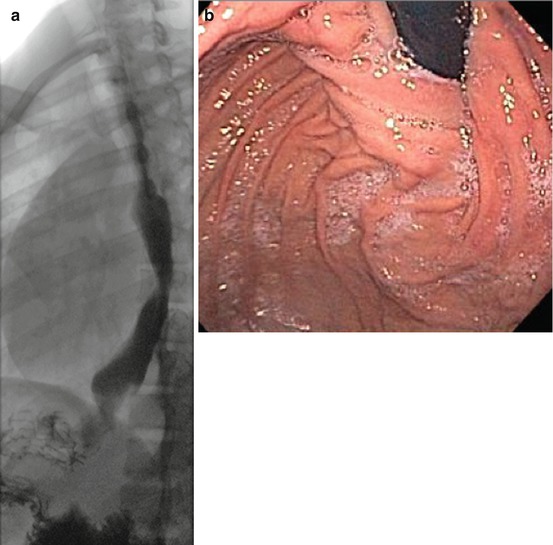

Fig. 17.4

Corroborative studies ((a) barium swallow, (b) upper endoscopy) indicating a defective fundoplication impeding esophageal emptying in a patient with prior Heller myotomy and Toupet fundoplication

Esophageal manometry is essential to confirm the diagnosis of achalasia and to measure the pressure of the lower esophageal sphincter. When compared to the preoperative test, it can show if the myotomy has been extended appropriately onto the gastric wall or if a residual high-pressure zone is still present (Fig. 17.5).

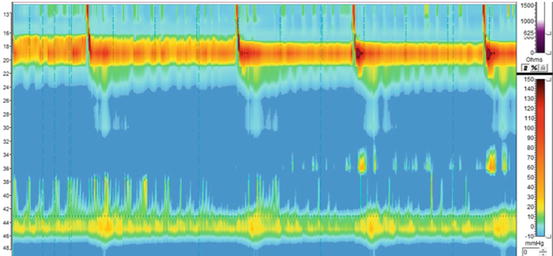

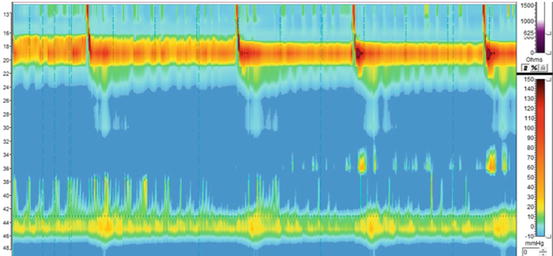

Fig. 17.5

High-resolution manometry of a patient with persistent dysphagia after a Heller myotomy confirming the diagnosis of achalasia with an aperistaltic esophagus and a non-relaxing lower esophageal sphincter

Ambulatory 24-h pH monitoring should be performed in patients with recurrent dysphagia, particularly if a cause for the dysphagia has not been found. It is important to not only look at the reflux score but to review the pH tracing to distinguish between real reflux and false reflux due to stasis and fermentation (Fig. 17.6a, b). This test should be routinely done even in asymptomatic patients after a Heller myotomy as reflux can be often “silent” [1]. This is particularly important when operating on children as a lifelong exposure to reflux can cause Barrett’s esophagus and even esophageal cancer [24, 26, 28].

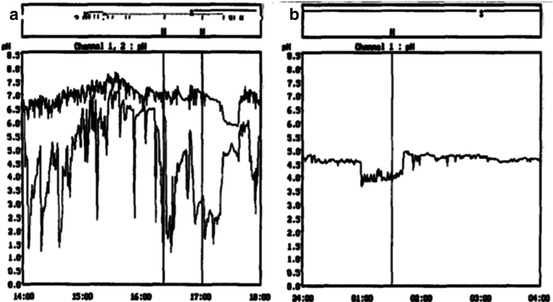

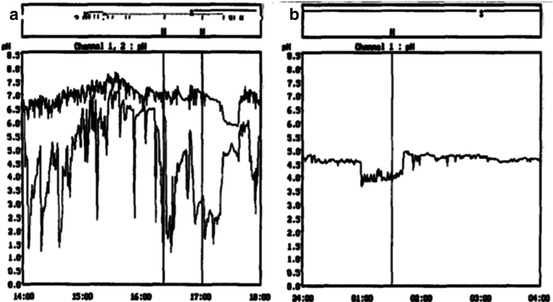

Fig. 17.6

24-h pH monitoring. (a) Real reflux. (b) False reflux

Sometimes patients have persistent dysphagia even though manometry shows achalasia and the myotomy has been properly performed. When pseudoachalasia secondary to the presence a submucosal tumor or a tumor outside the esophagus is suspected, endoscopic ultrasound and computed tomography can help establishing the diagnosis [29].

Treatment

Pneumatic Balloon Dilatation

A balloon dilatation should always be considered in patients with recurrent dysphagia. Contrary to common belief, the perforation rate is very low due to the fact that the myotomy is covered by the stomach if a Dor was performed or by the left lateral segment of the liver if a Toupet was added to the myotomy. Zaninotto et al. documented recurrent dysphagia in 9 of 113 patients (8 %) after laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Dor fundoplication [19]. Seven of the nine patients were effectively treated by balloon dilatation (median two dilatations, range 1–4), while two required a second operation. Similar results were described by Sweet et al. who reported on the effectiveness of dilatation for the treatment of both persistent and recurrent dysphagia [7].

Revisional Surgery

If dysphagia is not relieved by dilatations, a reoperation must be considered. When consenting the patient, it is important to stress that even though most cases can be performed laparoscopically, a laparotomy might be needed. In addition, patients must be aware that in case of severe damage to the mucosa during the course of the operation, an esophagectomy may be necessary.

The first step of the operation consists in separating the liver from the stomach and the esophagus. Subsequently, the fundoplication should be taken down and the fundus brought to the left in order to expose the esophageal wall. Adequate and complete exposure of the esophageal wall including a thorough dissection of the previous myotomy is the next step. Once this has been accomplished, and the area of narrowing is clearly identified, we prefer to correct the problem by performing a new myotomy (usually easier if done to the right of the previous myotomy, through the GEJ and extending it 3 cm onto the gastric wall, close to the lesser curvature). Rather than trying to extend the prior myotomy, it is easier to perform a new myotomy on the opposite side in order to work on an unscarred part of the esophageal wall [27] (Fig. 17.7). The myotomy should be extended for 3–4 cm below the GEJ, and intraoperative endoscopy should be performed to evaluate for inadvertent esophageal or gastric mucosal injury. After the myotomy is completed, consideration should be given whether or not to add a fundoplication. Certainly, if a mucosal injury has occurred, a Dor fundoplication may buttress the closure, decrease the chance of immediate complications, and prevent future reflux. However, in the absence of a perforation, our tendency has been to avoid performing a fundoplication. Our rationale is based on the fact that (a) dysphagia is the primary problem necessitating repeat intervention; (b) returning to the operating room a third time to relieve dysphagia is an increasingly difficult task; (c) occasionally, a fundoplication may contribute to dysphagia; and (d) abnormal reflux can be treated medically far easier than dysphagia. Loviscek et al. recently showed excellent results using this approach [27]. The outcome of 43 achalasia patients who underwent redo Heller myotomy for recurrent dysphagia between 1994 and 2011 was analyzed. Three patients underwent take down of the previous fundoplication only, while the remaining 40 patients had that and a redo myotomy that extended for 3 cm onto the gastric wall. Only about one quarter of these patients had recreation of a fundoplication. All patients were followed for at least 1 year after the operation. At a median follow-up of 63 months in 24 patients, 19 patients (79 %) reported improvement of dysphagia, with median overall satisfaction rating of 7 (range 3–10). Four patients required esophagectomy for persistent dysphagia. Similar results have been reported by others [30–32].