7 Restenosis and Drug-Eluting Stents

Restenosis

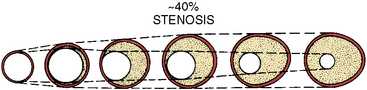

The second component of restenosis, recoil and negative remodeling of the arterial wall is inhibited by stents. Compared to balloon angioplasty, stents have reduced restenosis from 40% to 50% after percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) to 20% after bare-metal stenting. Drug-eluting stents (DESs) have brought restenosis rates to <10% in most patient subgroups. Restenosis still occurs inside stents (called in-stent restenosis [ISR]) mostly, if not exclusively, as a result of endothelial cell proliferation. Rarely does vascular recoil make a contribution, but it must be considered in treating the ISR lesion. Restenosis is not device-specific but rather a function of the anatomic substrate and the type of injury produced (Fig. 7-1).

Definitions of Restenosis

Angiographic Restenosis

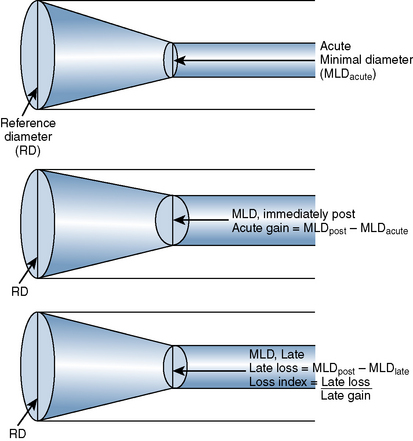

The late loss index is the loss at the lesion site divided by the amount of acute gain (Fig. 7-2). The loss index is accepted as the most sensitive measure of the effectiveness of the technique and should range from 0.4 to 0.6 mm for balloon angioplasty. The lower the loss index is, the more effective the antirestenosis treatment will be.

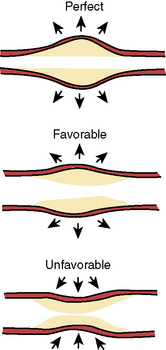

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) imaging is superior to angiography for anatomic and morphologic restenosis definitions. Recent IVUS studies have shown that an important component of restenosis is vessel recoil, a feature prevented by stenting. Normal vessel modeling maintains the coronary lumen. Late negative remodeling of the injured vessel is also prevented by stenting (Figs. 7-3 and 7-4).

Time Course

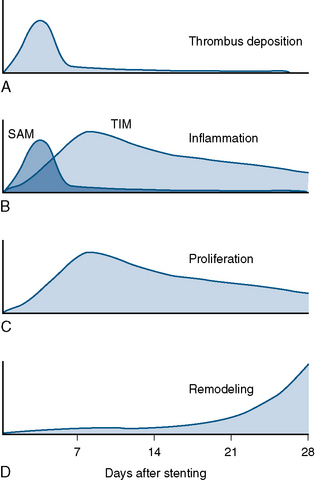

Different mechanisms produce restenosis in a time-dependent manner. Early restenosis is due to thrombus, whereas late restenosis is related more to remodeling (Fig. 7-5).