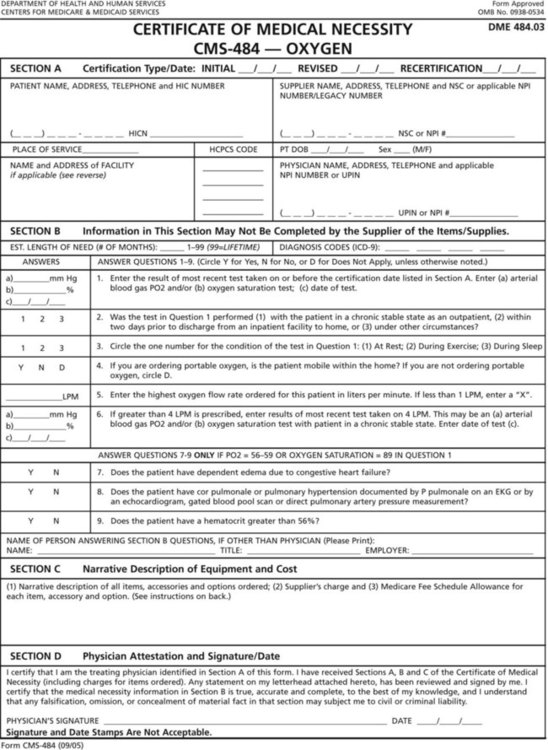

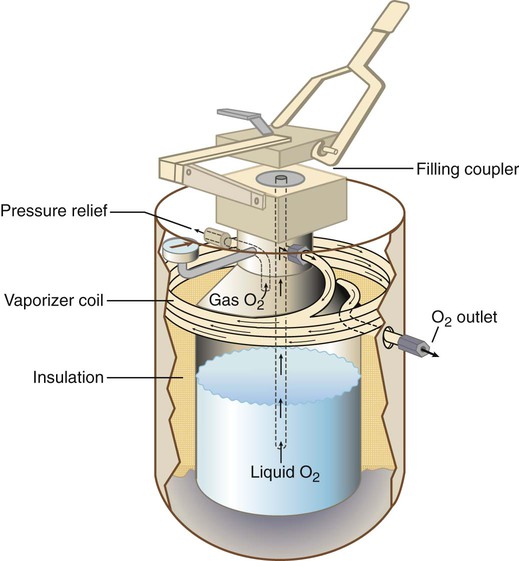

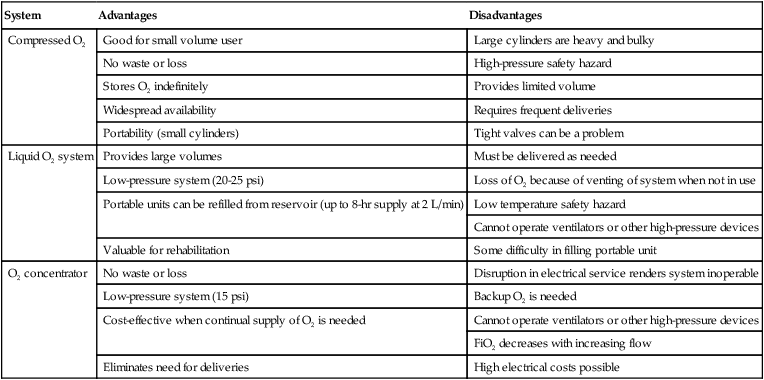

After reading this chapter you will be able to: With the introduction of Medicare in 1965, the cost savings and patient welfare benefits associated with home care and other nonacute care settings were recognized. This legislation established a reimbursement structure for health care services in alternative settings, including services provided at home. Since its adoption, Medicare is credited with substantial increases in the number of patients cared for at home. From 1967-1985, the number of home care agencies certified to participate in Medicare tripled to almost 6000. This figure peaked to slightly more 10,000 in 1997, the year in which the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) was introduced. The BBA of 1997, which is discussed in more detail in the following section, and other subsequent legislation had a monumental impact on health care reimbursement by reducing payments to durable medical equipment (DME) companies, home health agencies, and other alternative sites. Despite this reduction in reimbursement, however, approximately 10 million Americans continued to receive health care at home in 2007 at an estimated cost of approximately $50 million.1 Alternative health care settings offer the advantage of lower costs and enhanced patient comfort compared with acute care facilities. In 2007, the average daily acute care hospital charges were more than $4000 versus less than $1000 for SNFs.1 However, improper or premature discharging of patients to alternative care settings and poor care plan implementation can erase these benefits and result in short-term readmission. This problem is particularly relevant to respiratory care because it has been found that the short-term readmission rate for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is almost 20%.2,3 Proper patient screening and evaluation and appropriate discharge planning, including a multidisciplinary care plan, proper care plan implementation, and patient follow-up, can minimize the risk of readmission.4 This chapter provides relevant definitions, discusses more recent policy developments, discusses aspects of optimal discharge and patient care planning, and reviews various therapeutic respiratory modalities in alternative care sites. A major alternative site is the sleep laboratory where respiratory therapists (RTs) conduct polysomnography, or sleep studies; this facet of respiratory care is covered in Chapter 30, which focuses exclusively on the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of disorders of sleep. One of the most notable changes is the introduction of Medicare’s prospective payment system (PPS). Until the introduction of the PPS in the 1990s, Medicare mainly reimbursed providers such as home care agencies for “reasonable” charges up to a maximum monthly or one-time amount. However, under the PPS, reimbursement for many types of respiratory equipment in alternative sites is based on a predetermined monthly payment, adjusted for factors such as the health condition and geography. Additionally, certain types of respiratory equipment are categorized as capped-rental items. Capped-rental items are items eligible for reimbursement under the PPS for only a predetermined number of months, after which the equipment is deemed owned by the patient and rental payments cease. Other legislation that has substantially affected Medicare reimbursement includes the BBA of 1997 and the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005. Among other things, the BBA reduced reimbursement for home O2 by 25% in 1998 and another 5% in 1999. The Deficit Reduction Act modified the PPS further by again reducing monthly payment for selected respiratory equipment and adding to the list of capped-rental items. Under this legislation, modalities such as home O2 and bilevel positive airway pressure (bilevel PAP) with timed respiratory rate backup are capped at 36 months (O2) and 13 months (bilevel PAP). The net effect of these and subsequent reimbursement reductions has been much lower reimbursement for respiratory care equipment in alternative sites. This unfavorable trend continues to present challenges to agencies and facilities attempting to provide quality care to patients in such settings.5 At the time of the writing of this chapter, other policy and legislative changes have been enacted but not yet fully implemented. Most notable of these is the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010. There are many facets to this bill ranging from the expansion of health care coverage to many uninsured Americans, prohibiting the exclusion of preexisting conditions, and increasing the scope of coverage for certain types of preventive care. However, the provisions of this bill are still being closely examined, and modifications are likely. The exact impact of this bill and any related legislation on the U.S. health care system and the field of respiratory care remains to be seen.6 Another area that has been under review for some time is reimbursement for reasonable time spent by RTs in administering care and patient education in alternative care settings such as the home. Reimbursement under federal Medicare and state Medicaid programs applies only to respiratory equipment, such as home O2 and mechanical ventilators, and RT time is not covered. Although a few states have piloted programs to reimburse for certain therapies and education done by RTs in alternative settings, widespread acceptance has not occurred. Although Medicare provides limited payment for nursing and physical therapy at home, it generally does not reimburse for RTs in such a setting. The American Association for Respiratory Care (AARC), through its Government Affairs initiatives, continues to promote legislation and sponsor efforts to expand the recognition of RTs. As a result of the delicate balance among factors such as increasing health care costs, limited resources, and patient care, it appears that the PPS and other related policies will continue to be reviewed and modified by government agencies such as the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS).7 Other changes affecting RTs in alternative sites have resulted from research study outcomes. In 1999, a report from Muse and Associates to the AARC found that Medicare beneficiaries treated by RTs had better outcomes and lower cost in such facilities.8 More recently, other research projects have shown cost and quality benefits when RTs are involved in the management of patients receiving home O2 therapy and in outpatient asthma education programs.9 It is hoped that the Muse Report and the growing body of evidence stemming from other initiatives will help public agencies and private health care payers recognize the value of RTs in alternative care settings and shape policies accordingly. Advances in technology, research, and clinical specialization have permitted more acutely ill patients to be treated outside of large-scale, acute care hospitals. Over the past decade, LTACHs have become more prevalent. These facilities provide highly focused care to patients with complex medical conditions, including patients who have been ventilator-dependent and difficult to wean. Generally, LTACHs employ a highly experienced clinical staff, including RTs, to provide integrated interdisciplinary care using the latest equipment and specialized treatment protocols. During the 20- to 30-day typical length of stay at an LTACH, patients commonly experience significant improvement, including successful weaning from mechanical ventilation and increased tolerance for activities of daily living.10 According to the National Association of Subacute/Post Acute Care, subacute care is a comprehensive level of inpatient care for stable patients who (1) have experienced an acute event resulting from injury, illness, or exacerbation of a disease process; (2) have a determined course of treatment; and (3) require diagnostic or invasive procedures but not those requiring acute care.10 Typically, the severity of the patient’s condition requires active physician direction with frequent on-site visits, professional nursing care, significant ancillary services, and an outcomes-focused interdisciplinary approach employing a professional team. The goal of acute care is to apply intensive resources to stabilize patients after severe episodic illness, whereas subacute care aims to restore the whole patient back to the highest practical level of function—ideally self-care. This holistic approach requires goal-oriented interdisciplinary team care, with frequent assessment of progress and a time-limited plan of care.11 The AARC defines respiratory home care as specific forms of respiratory care provided in the patient’s place of residence by personnel trained in respiratory care working under medical supervision.12 The primary goal of home care is to provide quality health care services to patients in their home setting, minimizing their dependence on institutional care. In regard to respiratory home care, several specific objectives are evident. Respiratory home care can contribute to the following: • Supporting and maintaining life • Improving patients’ physical, emotional, and social well-being • Promoting patient and family self-sufficiency • Ensuring cost-effective delivery of care Although not all aspects of respiratory home care have proven effective, various studies have shown that carefully selected treatment regimens can be of significant benefit to patients. These benefits include increased longevity, improved quality of life, increased functional performance, and a reduction in the individual and societal costs associated with hospitalization.13,14 Most reimbursement for care in alternative settings is through either the federal Medicare program or federal or state Medicaid programs. As the largest purchaser of health services, the federal government (in connection with state and local governments) plays a major role in setting standards and regulating this industry. The federal agency responsible for the overall administration of Medicare and Medicaid is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Created in 1997, CMS oversees the framework for providing health coverage to elderly adults, disabled adults, and many disadvantaged young children in the United States.5,6 As part of this structure, CMS created the Medicare Provider Certification Program. This program ensures that institutional providers that serve Medicare beneficiaries, including hospitals, SNFs, LTACHs, home health agencies, and assisted living facilities, meet minimum health and safety requirements. These requirements are called conditions of participation. Current conditions of participation emphasize quality indicators, outcome measures, and cost efficiency designed to improve the quality and effectiveness of care provided to beneficiaries.5,6 Institutions undergo certification surveys to determine their compliance with the applicable conditions of participation. These surveys are conducted by either state survey agencies or private accrediting organizations, such as The Joint Commission (TJC), which is discussed in more detail in the following section.15,16 The primary organization responsible for standard setting and voluntary accreditation of care providers in alternative settings is TJC. To assist hospitals and health care organizations with the accreditation process and overall performance improvement, TJC develops and publishes standards and National Patient Safety Goals for long-term and subacute care, home care, and assisted living facilities. The standards cover general functional categories relating to quality patient care and the process and structure of the organization. These categories include patient rights, ethics, and assessment and organizational leadership and management of information. The patient safety goals target for improvement common problem areas for health care organizations, such as proper patient identification, medication safety, and infection control.15,16 In regard to home care, TJC applies different protocols to assess different types of home care agencies. The home equipment management protocol pertains only to companies that rent or sell home medical equipment. In most cases, this type of provider is involved only with basic O2 and aerosol therapy setups and does not provide in-depth visits for patient assessment or evaluation. Agencies involved with clinical respiratory services perform periodic home visits with patient assessment. Agencies applying for accreditation at this level are involved with more sophisticated forms of home care that require routine follow-up visits, such as management of artificial airways and ventilator-dependent patients. The standards for this type of home care accreditation are more extensive and rigorous.15,16 For the RT, working in the alternative care setting is distinctly different from working in an acute care hospital. Key differences involve resource availability, supervision and work schedules, documentation and assessment, and provider-patient interaction (Table 51-1).17 Although some practitioners do not like the alternative work settings, many find the greater independence, professional team orientation, creativity, and higher level of patient and family interaction quite rewarding. In addition, most RTs working in the alternative care environment argue that only in these settings is their full scope of training really used. TABLE 51-1 Effective discharge planning provides the foundation for quality care in the alternative care setting. A properly designed and implemented discharge plan guides the multidisciplinary team in successfully transferring a respiratory care patient from the health care facility to an alternative site of care.18 Effective implementation of the discharge plan also ensures the safety and efficacy of the patient’s continuing care. To guide practitioners in providing quality care, the AARC has published Clinical Practice Guideline: Discharge Planning for the Respiratory Care Patient.19 Excerpts from this guideline appear in Clinical Practice Guideline 51-1. Although a physician normally initiates an order to discharge a patient to an alternative site, many other health care professionals are involved in the discharge process. Table 51-2 identifies these key professionals and their major responsibilities.18 As with pulmonary rehabilitation (see Chapter 50), a team approach produces the best patient results. Communication and mutual respect for the talents and abilities of each team member are two key elements in making patient care in the alternative care setting work. Any breakdown in the system may delay or adversely affect patient discharge and the patient’s physical health and mental well-being. TABLE 51-2 Members of Patient Care Team in Alternative Settings The primary factors determining the appropriate site for discharge are the goals and needs of the patient. These goals and needs should be met in an optimal and cost-effective manner using the resources available at the proposed site. In terms of institutional personnel, the staff of the selected facility must have all the competencies required to meet the patient’s respiratory needs, be able to provide other needed health care services (e.g., physical therapy), and provide adequate 24-hour coverage.17,19 For discharge to the home, it is essential that the ability of caregivers to learn and perform the required care be evaluated before transfer. Caregivers must clearly demonstrate and have documented the competencies required to care for the specific patient and, in combination, provide 24-hour coverage.17,19 • Service 24 hours, 7 days a week • Third-party insurance processing • Home instruction and follow-up by an RT When selecting a DME supplier from the available choices, the patient and family members and other members of the discharge planning team should consider the company’s accreditation status, cost and scope of services, dependability, location, personnel, past track record, and availability. To help ensure a basic level of quality, one should select a DME supplier that is accredited. In addition, the service should be problem-free and provided by reliable, experienced, professional, and courteous staff. Charges should be reasonable and competitive, and clinical respiratory services should be provided by credentialed RTs.17 Finally, the selected site must meet basic safety standards and be suitable for managing the patient’s specific condition. It should be free of fire, health, and safety hazards; provide adequate heating, cooling, and ventilation; provide adequate electrical service; and provide for patient access and mobility with adequate patient space (room to house medical and adaptive equipment) and storage facilities. The selected site must be capable of operating, maintaining, and supporting all equipment needed by the patient; including both respiratory and ancillary equipment and supplies as needed, such as the ventilator, suction, O2, intravenous therapy, nutritional therapy, and adaptive equipment.17,19 Box 51-1 lists key factors one should assess in planning the discharge of a respiratory care patient to the home environment. O2 therapy is the most common mode of respiratory care in alternative care settings. This high use is based on the fact that O2 therapy improves both survival and quality of life in selected patient groups, especially patients with advanced COPD.20,21 In particular, studies have shown improved nocturnal O2 saturation, reduced pulmonary artery pressure, and lower pulmonary vascular resistance with appropriate outpatient O2 therapy.22,23 To guide practitioners in providing quality care, the AARC has published a Practice Guideline on Oxygen Therapy in the Home or Extended Care Facility.24 Excerpts from the AARC guideline, including the indications, contraindications, precautions and possible complications, method, assessment of need, assessment of outcome, and monitoring, appear in Clinical Practice Guideline 51-2. As indicated in Clinical Practice Guideline 51-2, O2 prescriptions must be based on documented hypoxemia, as determined by either arterial blood gas analysis or oximetry. Prescriptions for O2 therapy no longer can be based simply on patient diagnosis or signs and symptoms. In addition, as-needed O2 therapy is no longer acceptable in the alternative care setting. When the need for O2 therapy is established, the physician writes a prescription. A prescription for O2 therapy in the alternative care setting must include the following elements:25 • Flow rate in L/min or concentration or both • Frequency of use in hours per day and minutes per hour (if applicable) • Diagnosis (severe primary lung disease, secondary conditions related to lung disease and hypoxia, related conditions or symptoms that may improve with O2) • Laboratory evidence (arterial blood gas analysis or oximetry under the appropriate testing conditions); home care companies cannot provide this testing • Additional medical documentation (no acceptable alternatives to home O2 therapy) For home use, the ordering physician must authorize O2 therapy using the CMS Certification of Medical Necessity form for O2 (Figure 51-1). After the need for long-term therapy is documented, repeat arterial blood gas analysis or SpO2 measurements are not needed. However, blood O2 levels may still be measured when the need arises to assess changes in the patient’s condition.26 Most alternative care sites do not have bulk O2 storage or delivery systems. In these settings, O2 normally is supplied from one of the following three sources:27 (1) compressed O2 cylinders, (2) liquid O2 systems, or (3) O2 concentrators. Table 51-3 summarizes the major advantages and disadvantages of each system. TABLE 51-3 Advantages and Disadvantages of Major Alternative Oxygen Supply Systems The primary use of compressed O2 cylinders in alternative settings is either for ambulation (small cylinders) or as a backup to liquid or concentrator supply systems (H/K cylinders). Safety measures for cylinder O2 are the same as those discussed in Chapters 37 and 38. For home use, the RT should thoroughly review these safety measures with both the patient and family members. After instruction, the RT should always confirm and document abilities of caregivers to use the delivery system safely. In addition to the cylinder gas, a pressure-reducing valve with flowmeter is needed to deliver O2 at the prescribed flow. Standard clinical flowmeters deliver flows up to 15 L/min; flows used in alternative settings are typically in the 0.25 to 5 L/min range. For this reason, the RT should select a calibrated low-flow flowmeter whenever possible. Alternatively, a preset flow restrictor can be used (see Chapter 37). As in the hospital, there is usually no need to humidify nasal O2 at flows of 4 L/min or less.24 If humidification is needed, a simple unheated bubble humidifier can be used. Because the mineral content of tap water may be high (hard water), water used in these humidifiers should be distilled. Otherwise, the porous diffusing element may become occluded. Although complete blockage is unlikely, occlusion of the diffusing element can impair humidification and alter flow. Because 1 cubic ft of liquid O2 equals 860 cubic ft of gas, liquid O2 systems can store large quantities of O2 in small spaces; this is ideal for the high-volume user. As shown in Figure 51-2, a typical personal liquid O2 system is a miniature version of a hospital stand tank. Similar to its larger counterpart, this system consists of a reservoir unit similar in design to a thermos bottle. The inner container of liquid O2 is suspended in an outer container, with a vacuum in between. The liquid O2 is kept at approximately −300° F. Because of constant vaporization, gaseous O2 always exists above the liquid. When the cylinder is not in use, this vaporization maintains pressures between 20 psi and 25 psi. When pressures increase above this level, gas vents out the pressure relief valve.

Respiratory Care in Alternative Settings

Describe alternative care settings in which respiratory care is often performed.

Describe alternative care settings in which respiratory care is often performed.

Discuss more recent developments and trends in respiratory care at alternative sites.

Discuss more recent developments and trends in respiratory care at alternative sites.

Identify who regulates alternative care settings.

Identify who regulates alternative care settings.

List the standards that apply to the delivery of respiratory care in alternative settings.

List the standards that apply to the delivery of respiratory care in alternative settings.

Describe how to help formulate an effective discharge plan.

Describe how to help formulate an effective discharge plan.

List factors to evaluate when assessing alternative care sites and support services.

List factors to evaluate when assessing alternative care sites and support services.

Discuss how to justify, provide, evaluate, and modify oxygen (O2) therapy in alternative care settings.

Discuss how to justify, provide, evaluate, and modify oxygen (O2) therapy in alternative care settings.

Explain how to select, assemble, monitor, and maintain O2 therapy equipment in alternative settings.

Explain how to select, assemble, monitor, and maintain O2 therapy equipment in alternative settings.

Identify the special challenges that exist in providing ventilatory support outside an acute care hospital.

Identify the special challenges that exist in providing ventilatory support outside an acute care hospital.

Describe how to instruct patients or caregivers and confirm their ability to provide care in alternative settings.

Describe how to instruct patients or caregivers and confirm their ability to provide care in alternative settings.

Identify which patients benefit the most from ventilatory support outside acute care hospitals.

Identify which patients benefit the most from ventilatory support outside acute care hospitals.

Explain how to select, assemble, monitor, and maintain portable ventilatory support and continuous positive airway pressure equipment, including applicable interfaces or appliances.

Explain how to select, assemble, monitor, and maintain portable ventilatory support and continuous positive airway pressure equipment, including applicable interfaces or appliances.

Describe proper documentation regarding patient evaluation and progress in alternative settings.

Describe proper documentation regarding patient evaluation and progress in alternative settings.

State how to ensure safety and infection control in alternative patient care settings.

State how to ensure safety and infection control in alternative patient care settings.

More Recent Developments and Trends

Relevant Terms and Goals

Long-Term Subacute Care Hospitals

Subacute Care

Home Care

Standards

Regulations

Private Sector Accreditation

Traditional Acute Care Versus Alternative Setting Care

Area

Traditional Setting (Acute Care Hospital)

Alternative Settings (Long-Term Acute Care, Subacute, Home Care)

Diagnostic resources

In-house laboratory, x-ray, ABG analysis, PFT

Must rely on outside vendors to provide diagnostic tests

Equipment support

Extensive; supported by piped-in O2 and suctioning

Limited availability; must use portable O2 and suctioning systems

Travel requirements

None; remain in one facility

Must travel between facilities or residences

Level of supervision

Direct supervision

Respiratory care provider works independently with minimal supervision

Patient assessment

Moderate—primarily provided by attending physician or residents

Heavy—core responsibility related to care planning

Documentation requirements

Moderate—limited to medical recordkeeping

Heavy—includes initial justification, ongoing follow-up, and often detailed financial recordkeeping

Work schedule

Specific hours

Varied work schedule, often including “on-call” off hours coverage

Time constraints

More than one shift to deliver therapy

Must complete all therapy during shift or visit

Patient-family interaction

Limited treatment time available; little family interaction

One-on-one therapy; intensive family interaction

Provider interaction

Primarily attending physicians and patient’s nurses

Continuous interaction with all members of professional team

Discharge Planning

Multidisciplinary Team

Discipline

Responsibilities

Utilization review

Advises or recommends consideration of patient discharge. Documents patient’s in-hospital care

Discharge planning (social service or community or public health)

Brings all the needed elements together and ensures that a patient can be discharged to alternative care sites. Makes contacts with outside agencies that may assist with patient care

Physician

Writes order for patient discharge. Evaluates patient’s condition and prescribes needed care. Establishes therapeutic objectives

Respiratory care

Evaluates patient and recommends appropriate respiratory care. Provides care and follow-up

Nursing

Writes and implements nursing care plan for patient. Assesses patient’s status and provides necessary follow-up

Dietary and nutrition

Assesses patient’s nutritional needs and writes dietary plan for patient. Makes arrangements for meals as necessary

Physical and occupational therapy

Provides necessary physical therapy and recommends any additional modalities or procedures

Psychiatry or psychology

Assesses patient’s emotional status and provides any needed counseling or support

DME supplier or home care company

Provides needed equipment and supplies and handles any emergency situations involving delivery or equipment operation

Site and Support Service Evaluation

Oxygen Therapy in Alternative Settings

Oxygen Therapy Prescription

Supply Methods

System

Advantages

Disadvantages

Compressed O2

Good for small volume user

Large cylinders are heavy and bulky

No waste or loss

High-pressure safety hazard

Stores O2 indefinitely

Provides limited volume

Widespread availability

Requires frequent deliveries

Portability (small cylinders)

Tight valves can be a problem

Liquid O2 system

Provides large volumes

Must be delivered as needed

Low-pressure system (20-25 psi)

Loss of O2 because of venting of system when not in use

Portable units can be refilled from reservoir (up to 8-hr supply at 2 L/min)

Low temperature safety hazard

Cannot operate ventilators or other high-pressure devices

Valuable for rehabilitation

Some difficulty in filling portable unit

O2 concentrator

No waste or loss

Disruption in electrical service renders system inoperable

Low-pressure system (15 psi)

Backup O2 is needed

Cost-effective when continual supply of O2 is needed

Cannot operate ventilators or other high-pressure devices

FiO2 decreases with increasing flow

Eliminates need for deliveries

High electrical costs possible

Compressed Oxygen Cylinders

Liquid Oxygen Systems

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Respiratory Care in Alternative Settings