Figure 35.1

The basic premise of our surgical approach involves complete en bloc removal of the RM, thymus, and surrounding involved structures. Surgery for PMNSGCT is technically demanding because preoperative chemotherapy renders surrounding mediastinal tissues fibrotic, obscuring normal anatomic planes. The effectiveness of cisplatin-based chemotherapy for germ cell cancer, however, also usually results in extensive tumor necrosis that is more marked around the periphery. This finding usually allows a complete resection that minimizes operative morbidity by preserving critical structures that abut but are not densely adherent to nor directly involved with the RM, such as lung, great veins, phrenic nerves, and occasionally cardiac chambers in which the “pericardial barrier” has been violated. In general, we believe an aggressive approach to remove all visible residual disease, but balanced dissection sparing critical structures with generous use of frozen section analysis, is warranted. This approach has allowed resection of virtually all RMs, including extremely large ones, with tumor-free margins. Although all PMNSGCT arise in the anterior mediastinal compartment, the exact location, size, and degree of adjacent organ involvement of postchemotherapy masses are variable. Therefore, the most critical decision initially is determination of the surgical approach. A median sternotomy, bilateral anterior thoracotomy with transverse sternotomy (the so-called clamshell incision), or anterolateral thoracotomy is chosen to optimize dissection around critical structures likely to be encountered during surgery. Based on referred cases to our institution, we currently use the sternotomy and clamshell approaches with approximately equal frequency. A thoracotomy approach is used for less common lateralized RMs, in which there is no substernal component. A sternotomy approach typically is employed for a midline RM or a midline RM with modest to moderate extension into the right chest. With the use of sternal retractors to mobilize internal thoracic arteries for coronary bypass procedures and instruments designed for minimally invasive pulmonary surgery, en bloc right upper and middle lobectomies, if necessary, can be accomplished through this approach

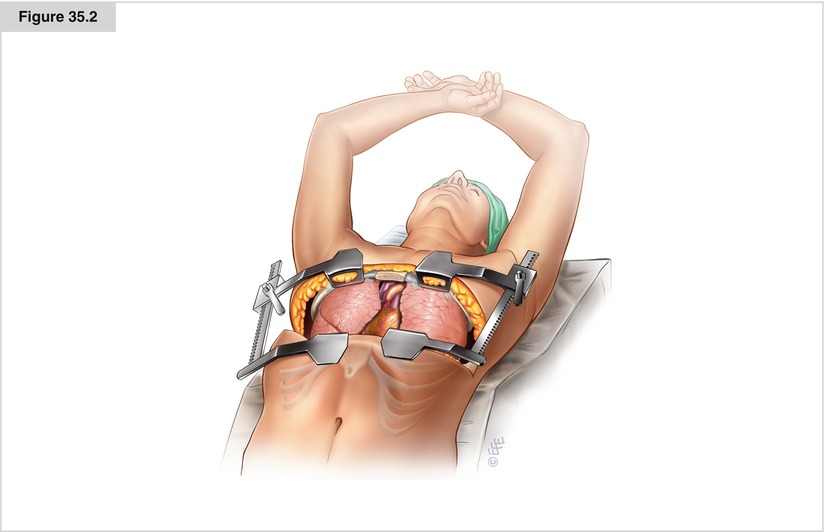

Figure 35.2

A clamshell approach provides the exposure required for midline tumors with significant extension into the right chest. This approach also is used for a substernal RM with anything more than slight extension into the left chest, as the heart makes it difficult to remove a large RM significantly invading the left lung. The patient is positioned supine with both arms crossed, padded, and then secured to an ether screen above the head. Following resection, it is important to perform longitudinal stabilization with short-length but threaded Kirschner pins carefully placed across the transverse sternotomy in addition to standard sternal wires to avoid painful sternal nonunion and secondary subluxation. On a final note, rare patients with both significant substernal and pleural space involvement in which the RM extends inferiorly to the diaphragm may benefit from a sequential sternotomy then thoracotomy approach, as inferior dissection is difficult through a clamshell incision

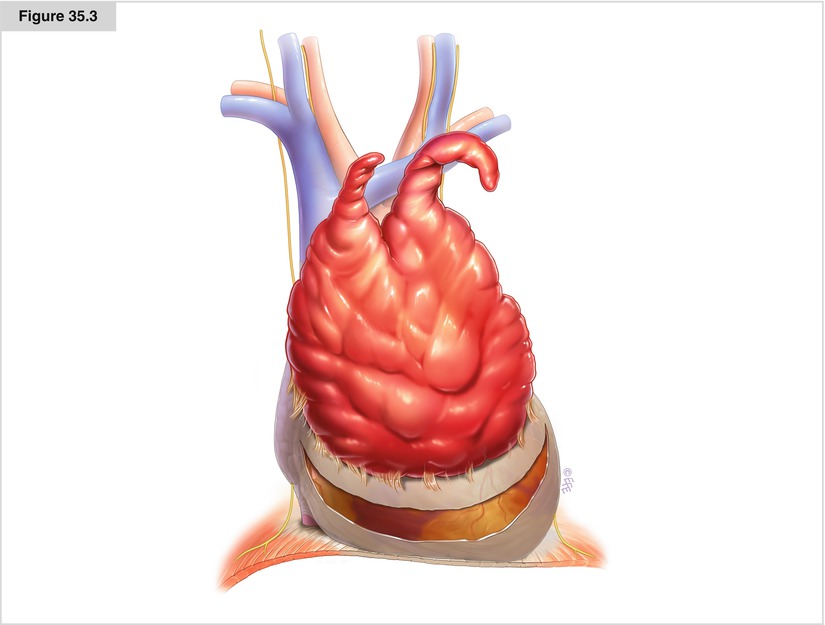

Figure 35.3

For most patients who do not demonstrate CT evidence of frank chest wall/sternal involvement, we begin with an extrapleural dissection until it can be determined that the RM does or does not involve the parietal pleura. The pleural space is entered at any point if the RM is found not to be adherent. If the RM is adherent, then at least a 1-cm rim of visibly normal parietal pleura is removed en bloc. Unfortunately, given the variability in location, size, and degree of the adjacent organ involvement of postchemotherapy masses, there is no consistent step-by-step surgical routine. In general, however, a surgical strategy proceeding from the easiest to the most difficult works best. Typically, we begin by dissecting adherent lung tissue from the RM, particularly if this involves lysis of filamentous adhesions or a stapled wedge resection removing a rim of lung parenchyma more densely adherent to the RM. Stapled wedge resection may be facilitated by passage of a red rubber catheter between the RM and pulmonary hilum for elevation and lateral retraction of the lung parenchyma before stapler division. Invasion of the RM into a significant amount of pulmonary parenchyma or pulmonary hilum usually requires formal anatomic resection, which may be done at this point or after further dissection. In our institution’s experience, more than half of PMNSGCT patients require some form of en bloc pulmonary resection. Formal lobectomy has been required in approximately a third of patients, wedge resection in 20 %, and total pneumonectomy in 5 %. We typically proceed with dissection of uninvolved tissues superior and inferior to the RM. The thymic horns rarely are involved and may be mobilized from the neck easily. Below, the pericardial fat is mobilized along with uninvolved contiguous thymic tissue to within 1 cm of the RM. Typically, the RM is densely adherent to the pericardium. Because there is little downside to pericardectomy, no attempt is made to separate the RM from the pericardium and the pericardium removed en bloc with a 1-cm tumor-free margin. Inspection of underlying cardiac structures, including a determination of whether the RM has transgressed the pericardial barrier, is made at this time. Occasionally, inflammatory adhesions to the epicardial surface are present and may be lysed with frozen section control. Division of the pericardium around the inferior aspect of the RM also may facilitate dissection around more critical structures, such as great veins and phrenic nerves. Following resection, pericardial reconstruction should be performed for most defects, using either fenestrated thin-walled polytetrafluoroethylene or absorbable mesh to eliminate the possibility of cardiac herniation

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree