INDICATIONS/CONTRAINDICATIONS

Reoperative antireflux surgery is a complex operation, and the success of the operation is strongly correlated with the surgeon’s experience, the patient’s symptom complex, and the findings of detailed objective tests. Performance of the surgery by an inexperienced surgeon will increase the chances of a suboptimal result and the best shot at successful redo antireflux surgery is a first redo in experienced hands. Another important consideration is poor correlation between objective tests and clinical symptoms, which should raise concern when considering redo surgery. For example, if the original indications for surgery were unclear, such as a cough in the setting of a normal pH study and no evidence of a hiatal hernia, additional workup may be needed before considering a redo operation. However, obvious symptoms, such as dysphagia, dumping syndrome, excessive nausea, and chest pain, that were not present prior to the original antireflux operation and are now recalcitrant to medical therapy will frequently need reoperation, depending on the severity.

Failure of antireflux surgery can have numerous etiologies including misdiagnosis prior to the initial operation. Thus, one of the first steps when evaluating these patients is a thorough review of the history and testing performed prior to the original operation. If these considerations are in order, a failure of the original antireflux operation can be due to technical problems during the first operation, or later breakdown of the wrap. A hiatal hernia after antireflux surgery may be due to poor hiatal closure, delayed reherniation, or placement of the wrap on the tubularized cardia due to an unrecognized short esophagus. The cause of symptoms such as recurrent heartburn, regurgitation, and dysphagia should be thoroughly investigated with a barium esophagogram and esophageal physiology testing. Factors such as the type of symptoms (heartburn vs. dysphagia), the status of esophageal motor function, the number of prior antireflux operations, and the patient’s body mass index (BMI) should be strongly considered when counseling patients regarding the options when symptomatic after initial antireflux surgery.

For example, a patient with recurrent or persistent heartburn who has failed optimal medical therapy and with a positive DeMeester score, a barium swallow that demonstrates a recurrent or persistent hiatal hernia, reasonable peristalsis, a normal-range BMI, and a single prior antireflux operation should be considered an ideal patient for a redo fundoplication by an experienced esophageal surgeon. In our experience, many of these redo fundoplications can be performed laparoscopically. Again, it is important to stress that these cases should be performed by an experienced esophageal surgeon who is comfortable with advanced minimally invasive procedures.

Reoperation may be more complex in patients with some of the following characteristics.

Morbid obesity

Morbid obesity

Esophageal dysmotility

Esophageal dysmotility

Multiple prior antireflux procedures

Multiple prior antireflux procedures

In the setting of morbid obesity and the comorbidities of obesity, a patient with a failed antireflux surgery may be the ideal patient for an RNY.8 If an RNY is determined to be a reasonable option, then a full workup for bariatric surgery should be pursued. This might include nutritional counseling, psychiatric evaluation, attendance at a support group meeting, and review of all the implications regarding quality of life (QOL) and the range of potential complications. If the RNY is decided upon, the surgeon should be experienced in both advanced laparoscopic antireflux surgery and gastric bypass techniques. In some cases, this might be best accomplished by consultation with an established esophageal surgeon working with an experienced bariatric surgeon to deliver the best care for these complicated patients. Sound judgment is needed for all patients who undergo reoperative antireflux surgery and the more complex the case, the more experience is needed. In patients with a severely diseased esophagus, such as severe dysmotility, nondilatable strictures, multiple prior operations, and significant gastroparesis, an esophagectomy may be the best option.

In summary, the following two general groups of patients should be considered for reoperative antireflux surgery.

1. Those with intractable recurrent or persiste nt GERD symptoms after prior antireflux surgery.

2. Those with intractable symptoms (e.g., dysphagia, nausea, gas bloat, or pain) that began after the initial antireflux operation, persisted, and did not respond to conservative measures.

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

PREOPERATIVE PLANNING

The workup of a patient who presents with recurrent symptoms after a prior antireflux surgery is initiated with a detailed history of the evolution of symptoms. It is important to evaluate the original symptoms prior to the first operation, the response to medical therapy, and the findings of prior testing. This may identify an esophageal motility disorder that may have been missed or an incorrect indication for the original operation. You may also identify a number of potential warning signs that may have been overlooked and present serious obstacles to successful antireflux surgery including the following.

The presence of severe constipation that has not been resolved

The presence of severe constipation that has not been resolved

Chronic opiate usage, medically controlled or otherwise

Chronic opiate usage, medically controlled or otherwise

Atypical GERD symptoms with poor correlation with objective tests, such as a chronic cough with a normal DeMeester study

Atypical GERD symptoms with poor correlation with objective tests, such as a chronic cough with a normal DeMeester study

Poor esophageal motility

Poor esophageal motility

Morbid obesity with comorbidities

Morbid obesity with comorbidities

Irritable bowel syndromes

Irritable bowel syndromes

The presence of any one of these clinical entities may limit the success of what appears to be a technically sound antireflux operation. Of course, failure can occur in any setting if the technical approach was initially poor, or has changed in an unfavorable way since the initial operation, due to reherniation, crural breakdown, etc.

A detailed review of the original operative report focusing on esophageal mobilization, vagal preservation, division of the short gastric vessels, and crural repair (primarily or with mesh) should give further insight into the technical causes of failure of the prior antireflux operation. Symptomatic improvement or lack of relief after the original repair should be carefully assessed. In addition, it is important to determine if there was a change in the patient’s symptoms (e.g., heartburn before the operation but dysphagia afterward) and the exact timing of the return of symptoms.

During the assessment, it is essential to consider the patient’s BMI and any related comorbidities. There is a strong association between obesity and GERD, and RNY may be an attractive surgical option in severely obese patients with a failed fundoplication.9,10

In addition to a detailed history, a detailed physical examination, and a careful review of the prior operative notes, it is essential to obtain a barium esophagogram as one of the first steps in the workup of the symptomatic patient after antireflux surgery. This simple and inexpensive test is universally available and is extremely useful in defining the anatomy, and identifying the presence of a persistent or recurrent hiatal hernia, a paraesophageal hernia, a tight or twisted wrap with or without herniation, or a specific pattern of failure of the prior fundoplication. In some cases, the barium swallow may be all you need prior to reoperative surgery. In some cases, the esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) may allow the surgeon to define one of the classic patterns of failure. There are many ways that a prior antireflux operation can fail; these have been summarized previously and include crural disruption, transdiaphragmatic herniation of the fundoplication, breakdown of the fundoplication, slipped or misplaced Nissen, misdiagnosis of achalasia, loose fundoplication, or tight fundoplication.5,11–13

Upper endoscopy permits direct visualization of the mucosa with complete evaluation of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, and the fundoplication. The finding of esophagitis or esophageal stricture may contribute to the evaluation. Biopsies can be performed to evaluate for cancer and/or Barrett’s esophagus. Detailed evaluation of the fundoplication and hiatal anatomy will further give insight into the likely cause of failure. Frequently, one can identify subtle recurrent hiatal hernias, failure of the classic “stack of coins” on retroflex view, or a wrap that is simply too tight or too loose.

Repeat pH monitoring is helpful when primary symptoms are heartburn-related; however, it is clear that some patients may have a normal pH study and still have marked symptoms from a twisted wrap, too tight of a wrap, or a completely herniated and partially obstructing wrap. A repeat manometry is important in the workup of the patient with a failed Nissen, even if the prior manometry was normal, but is especially helpful in patients with predominant symptoms of dysphagia. Intractable bloating or gastroparesis may indicate vagal nerve compromise and gastric emptying studies may help in planning the best approach. All of these studies are very valuable in identifying the cause of the patient’s symptoms and help the surgeon tailor the best redo operation for the patient.11, 14, 15 After completion of all comprehensive testing, the surgeon and the patient discuss the findings and determine the best course of action, which may include continuation of medical therapy, redo fundoplication, conversion to an RNY, or esophagectomy or colon interposition. Factors to consider in determining the best course of action will depend on the dominant clinical symptoms (i.e., heartburn or dysphagia), baseline esophageal function on physiology testing, number and success of the prior antireflux operations, evidence of gastroparesis, and the patient’s BMI. A number of warning signs were listed earlier and must be considered prior to reoperation.

One example of a warning sign that may have been overlooked and may present serious obstacles to successful antireflux surgery is chronic constipation due to bowel abnormalities or simply due to chronic opiate usage. In this setting, one can anticipate extremes of gas bloating and recurrent GERD due to extremely poor downstream peristalsis. In some cases, simply resolving the chronic constipation can go a long way to improving symptoms of bloat, gas, and in some cases even typical GERD symptoms. Thus, in all patients with constipation, we first work on a bowel regimen that normalizes bowel movements. Consultation with an experienced gastroenterologist is essential to resolve these issues prior to surgery. We consider chronic opiate usage a very serious warning sign that a simple Nissen may be technically adequate but postoperatively, the patient may be troubled by excessive gas, bloat, abdominal cramps, nausea, and failure to reach a satisfactory resolution of GERD symptoms. In this setting, we give strong consideration to the possibility of first working on a satisfactory bowel regimen, then reassessing the patient to see if indeed some of the GERD symptoms have resolved. We have seen many cases where a patient troubled by GERD and on chronic opiates with severe constipation is managed with a successful bowel regimen, and the GERD symptoms markedly improve. This is becoming an increasingly familiar clinical problem, and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) has noted a clear epidemic of the legal use and abuse of prescription narcotics and has estimated that the prescribing of narcotics in the United States has increased over 600% in the past decade.16 In some of these patients, aggressive proton pump inhibitor (PPI) use, bowel regimens to control constipation, or working with the patient and the pain clinic to lower or completely eliminate the opiate, if possible, may resolve the GERD symptoms.

In summary, assessment of patients with failed fundoplication contains the following steps.

A detailed history and physical examination with review of all prior testing and records.

A detailed history and physical examination with review of all prior testing and records.

A comprehensive evaluation that includes an endoscopy and a barium esophagogram, and frequently manometry, pH testing, and gastric emptying studies.

A comprehensive evaluation that includes an endoscopy and a barium esophagogram, and frequently manometry, pH testing, and gastric emptying studies.

Establishing a correlation between clinical symptoms and objective testing to tailor an appropriate redo operation.

Establishing a correlation between clinical symptoms and objective testing to tailor an appropriate redo operation.

SURGERY

SURGERY

Esophageal-preserving surgical options for redo antireflux surgery include redo fundoplication (partial or complete) and RNY. To provide the best outcome, an individualized approach based on the cause of fundoplication failure, the overall esophageal motility, and the patient’s BMI is necessary. As a last resort, an esophagectomy or a colon interposition may be the only viable option. Operative technique for redo fundoplication and RNY will be discussed.

Key factors to consider when selecting the type of operative approach include the following.

Redo fundoplication is ideal for a first-time redo in patients who have preserved esophageal function, an obvious anatomic wrap failure, objective evidence of recurrent reflux, and who are not obese.

Redo fundoplication is ideal for a first-time redo in patients who have preserved esophageal function, an obvious anatomic wrap failure, objective evidence of recurrent reflux, and who are not obese.

RNY should be considered in obese patients with recurrent symptoms and multiple comorbidities.

RNY should be considered in obese patients with recurrent symptoms and multiple comorbidities.

For very complex settings, such as patients with multiple failed redo operations, poor esophageal motility, and associated gastroparesis, going straight to minimally invasive esophagectomy with a high intrathoracic anastomosis and narrow gastric tube may be considered.

For very complex settings, such as patients with multiple failed redo operations, poor esophageal motility, and associated gastroparesis, going straight to minimally invasive esophagectomy with a high intrathoracic anastomosis and narrow gastric tube may be considered.

Positioning

Once the patient is under general anesthesia, an arterial line, a Foley catheter, and adequate intravenous access are placed. The patient is placed supine in reverse Trendelenburg position with his or her arms out. In anticipation for a long operative case, all pressure points need to be padded.

Operative Technique for Redo Fundoplication

The principles of reoperative antireflux surgery, whether minimally invasive or open, are the same. The focus should be on first carefully assessing the existing anatomy, reestablishing the normal anatomy (step by step), preserving vagal integrity, preserving crural integrity if possible, looking for and recognizing a short esophagus and performing an esophageal-lengthening procedure when necessary, identifying the need for crural reinforcement, and properly constructing the fundoplication. The operation should be performed at a center with extensive experience in reoperative esophageal surgery.

On-table endoscopy is performed to evaluate the esophagus, the stomach, and the fundoplication. An assessment of the mucosa is essential to rule out the presence of Barrett’s esophagus or neoplasm that might change the operative plan.

On-table endoscopy is performed to evaluate the esophagus, the stomach, and the fundoplication. An assessment of the mucosa is essential to rule out the presence of Barrett’s esophagus or neoplasm that might change the operative plan.

The abdomen is prepped and draped, and the initial port is placed away from prior incisions via a cut-down technique to allow safe entry into the abdomen. In most cases, we are able to perform laparoscopic lysis of adhesions to allow the remaining ports to be placed under direct visualization. However, the surgeon should not hesitate to open the abdomen, if needed, at any time.

The abdomen is prepped and draped, and the initial port is placed away from prior incisions via a cut-down technique to allow safe entry into the abdomen. In most cases, we are able to perform laparoscopic lysis of adhesions to allow the remaining ports to be placed under direct visualization. However, the surgeon should not hesitate to open the abdomen, if needed, at any time.

The upper abdomen is explored and additional lysis of adhesions is performed to free the liver from the prior fundoplication. The caudate lobe of the liver is identified, which will allow the surgeon to recognize the right crus. Right and left crural mobilization is performed from the liver and the spleen, respectively, paying particular attention to preserving the integrity of the crus.

The upper abdomen is explored and additional lysis of adhesions is performed to free the liver from the prior fundoplication. The caudate lobe of the liver is identified, which will allow the surgeon to recognize the right crus. Right and left crural mobilization is performed from the liver and the spleen, respectively, paying particular attention to preserving the integrity of the crus.

Frequently, it is necessary to go from side to side, moving from areas of recognizable anatomy, and into more difficult areas carefully. We frequently first work a little lower on the crus muscle and identify normal planes and carefully move up the crus.

Frequently, it is necessary to go from side to side, moving from areas of recognizable anatomy, and into more difficult areas carefully. We frequently first work a little lower on the crus muscle and identify normal planes and carefully move up the crus.

Once the crura have been identified, we attempt to remove crural sutures and open the posterior mediastinum.

Once the crura have been identified, we attempt to remove crural sutures and open the posterior mediastinum.

Next, we carefully work along the crural planes laterally into the mediastinum, attempting to avoid injury to the vagus nerves, and avoid entering the pleura. Early entry into the pleura may necessitate placing a pigtail catheter into the respective pleural space. As we move into the mediastinum, we can frequently see the esophagus and vagus nerves proximally. We carefully continue this plane of dissection and then begin to move anteriorly.

Next, we carefully work along the crural planes laterally into the mediastinum, attempting to avoid injury to the vagus nerves, and avoid entering the pleura. Early entry into the pleura may necessitate placing a pigtail catheter into the respective pleural space. As we move into the mediastinum, we can frequently see the esophagus and vagus nerves proximally. We carefully continue this plane of dissection and then begin to move anteriorly.

As one moves either anteriorly or posteriorly, care must be taken to preserve vagal integrity. We avoid going directly between the two limbs of the wrap in the initial phases of the reoperation as the vagus nerves are particularly at risk early in the reoperation before the anatomy is identified.

As one moves either anteriorly or posteriorly, care must be taken to preserve vagal integrity. We avoid going directly between the two limbs of the wrap in the initial phases of the reoperation as the vagus nerves are particularly at risk early in the reoperation before the anatomy is identified.

Sharp dissection with the ultrasonic shears or other device will provide a relatively bloodless field allowing safe recognition of important structures.

Sharp dissection with the ultrasonic shears or other device will provide a relatively bloodless field allowing safe recognition of important structures.

At any point in the operation, where progress is not safe, we will move to another area and reassess there. For example, assessing slightly lower on the greater curvature of the stomach and taking down the short gastric vessels and dissecting up toward the left crus from below can be a rewarding plane in some cases.

At any point in the operation, where progress is not safe, we will move to another area and reassess there. For example, assessing slightly lower on the greater curvature of the stomach and taking down the short gastric vessels and dissecting up toward the left crus from below can be a rewarding plane in some cases.

As we work on the right or left crus, knowledge of the operative steps during the initial operation(s) is essential. Knowing if the vagal nerves were left inside the wrap (as in most cases) or outside the wrap or if mentioned at all can be helpful.

As we work on the right or left crus, knowledge of the operative steps during the initial operation(s) is essential. Knowing if the vagal nerves were left inside the wrap (as in most cases) or outside the wrap or if mentioned at all can be helpful.

If the wrap was tacked to the right and left crus, it is very easy to inadvertently enter the stomach. Again, we frequently go back and forth from the right crus to the left, looking for areas of safe progress. Once we have some identification of the stomach and wrap limbs, we generally start on the left limb of the wrap and gently work inside of this, sweeping any fat or tissue centrally, assuming the anterior vagus is between the suture limbs of the wrap. As this is done, removal of fundoplication sutures can safely be done from just on the undersurface of the wrap on the left, thereby preserving the anterior vagal trunk. Once this is done, one can frequently pick up the right limb of the wrap, sweep inside of this, and gently clear the esophageal side of the wrap until both limbs of the gastric wrap are mobilized.

If the wrap was tacked to the right and left crus, it is very easy to inadvertently enter the stomach. Again, we frequently go back and forth from the right crus to the left, looking for areas of safe progress. Once we have some identification of the stomach and wrap limbs, we generally start on the left limb of the wrap and gently work inside of this, sweeping any fat or tissue centrally, assuming the anterior vagus is between the suture limbs of the wrap. As this is done, removal of fundoplication sutures can safely be done from just on the undersurface of the wrap on the left, thereby preserving the anterior vagal trunk. Once this is done, one can frequently pick up the right limb of the wrap, sweep inside of this, and gently clear the esophageal side of the wrap until both limbs of the gastric wrap are mobilized.

Once both limbs are mobilized completely, the wrap is freed completely from the right and posterior crus and tucked back under the esophagus into its normal anatomic location.

Once both limbs are mobilized completely, the wrap is freed completely from the right and posterior crus and tucked back under the esophagus into its normal anatomic location.

If we can pick up the fundic tip and it lifts easily and completely, then we consider that near-normal anatomy is reestablished. At this point, we completely remove the fat pad, starting from the angle of His and moving from the left crus side toward the right. We avoid the anterior vagus and identify the true esophageal wall as it meets the stomach.

If we can pick up the fundic tip and it lifts easily and completely, then we consider that near-normal anatomy is reestablished. At this point, we completely remove the fat pad, starting from the angle of His and moving from the left crus side toward the right. We avoid the anterior vagus and identify the true esophageal wall as it meets the stomach.

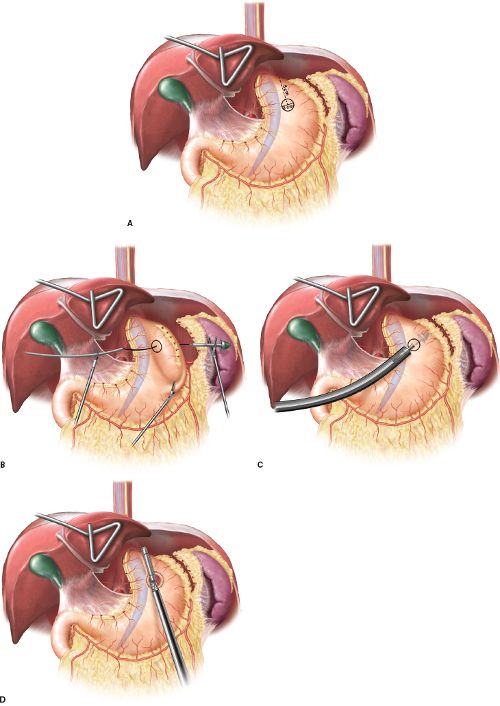

Next, we completely mobilize the esophagus into the mediastinum and assess the esophageal length to determine if it is adequate. Ideally, 2.5 to 3 cm of tension-free intra-abdominal esophageal length should be established. If we do not have this length, we first attempt to mobilize the esophagus more proximally to gain additional length. If the esophagus is still short, a Collis gastroplasty should be strongly considered. Collis gastroplasty can be performed with a bougie in the esophagus, using a circular end-to-end anastomotic (EEA) technique (Fig. 8.1), but is more commonly performed with a wedge gastroplasty (Fig. 8.2).

Next, we completely mobilize the esophagus into the mediastinum and assess the esophageal length to determine if it is adequate. Ideally, 2.5 to 3 cm of tension-free intra-abdominal esophageal length should be established. If we do not have this length, we first attempt to mobilize the esophagus more proximally to gain additional length. If the esophagus is still short, a Collis gastroplasty should be strongly considered. Collis gastroplasty can be performed with a bougie in the esophagus, using a circular end-to-end anastomotic (EEA) technique (Fig. 8.1), but is more commonly performed with a wedge gastroplasty (Fig. 8.2).

An on-table endoscopy is again performed to evaluate any inadvertent esophageal or gastric perforations. It is very easy to miss a small gastric enterotomy, and these injuries should be repaired before performing a fundoplication. If there is extensive damage to the gastroesophageal junction or the fundus, such that repair or a safe fundoplication cannot be constructed, a different surgical option, such as RNY or esophagectomy, should be considered. We always discuss these extreme situations with the redo patient before operation and the consent indicates these other options as “possible.”

An on-table endoscopy is again performed to evaluate any inadvertent esophageal or gastric perforations. It is very easy to miss a small gastric enterotomy, and these injuries should be repaired before performing a fundoplication. If there is extensive damage to the gastroesophageal junction or the fundus, such that repair or a safe fundoplication cannot be constructed, a different surgical option, such as RNY or esophagectomy, should be considered. We always discuss these extreme situations with the redo patient before operation and the consent indicates these other options as “possible.”

If performing a complete wrap, we do a floppy, two-stitch fundoplication on the esophagus over a 52 to 56 F bougie or on the neoesophagus if a Collis gastroplasty was performed. (Fig. 8.3). It is essential to deliver the fundus with proper orientation in an untwisted, nonspiraled fashion, as assessed by the “shoe-shine” maneuver.

If performing a complete wrap, we do a floppy, two-stitch fundoplication on the esophagus over a 52 to 56 F bougie or on the neoesophagus if a Collis gastroplasty was performed. (Fig. 8.3). It is essential to deliver the fundus with proper orientation in an untwisted, nonspiraled fashion, as assessed by the “shoe-shine” maneuver.

For patients with severe dysmotility or significant dysphagia, a partial wrap (Dor or Toupet) may be considered. In rare circumstances, in the setting of a very tight wrap that led to long-standing dysphagia, manometry testing may suggest pseudoachalasia. In these unusual cases, a distal myotomy may be needed in addition to converting the wrap to a partial fundoplication.

For patients with severe dysmotility or significant dysphagia, a partial wrap (Dor or Toupet) may be considered. In rare circumstances, in the setting of a very tight wrap that led to long-standing dysphagia, manometry testing may suggest pseudoachalasia. In these unusual cases, a distal myotomy may be needed in addition to converting the wrap to a partial fundoplication.

The crural repair completes the operation. The crura are approximated posteriorly with permanent suture. It is important to completely mobilize the right and left crus of the liver and the splenic attachments to allow tension-free primary closure. If the integrity of the crura is compromised or a tension-free closure cannot be achieved despite all efforts (e.g., inducing a left-side pneumothorax or lowering intra-abdominal pressure during laparoscopy), a biologic mesh should be used to reinforce the crural repair. Nonabsorbable mesh should be avoided at all costs due to the concern of delayed erosion into the esophagus.

The crural repair completes the operation. The crura are approximated posteriorly with permanent suture. It is important to completely mobilize the right and left crus of the liver and the splenic attachments to allow tension-free primary closure. If the integrity of the crura is compromised or a tension-free closure cannot be achieved despite all efforts (e.g., inducing a left-side pneumothorax or lowering intra-abdominal pressure during laparoscopy), a biologic mesh should be used to reinforce the crural repair. Nonabsorbable mesh should be avoided at all costs due to the concern of delayed erosion into the esophagus.

Figure 8.1 Collis gastroplasty performed with a transgastric EEA followed by a linear stapler. A–C: Anvil positioning of the EEA stapler. D: Creation of the neoesophagus with an Endo GIA stapler.