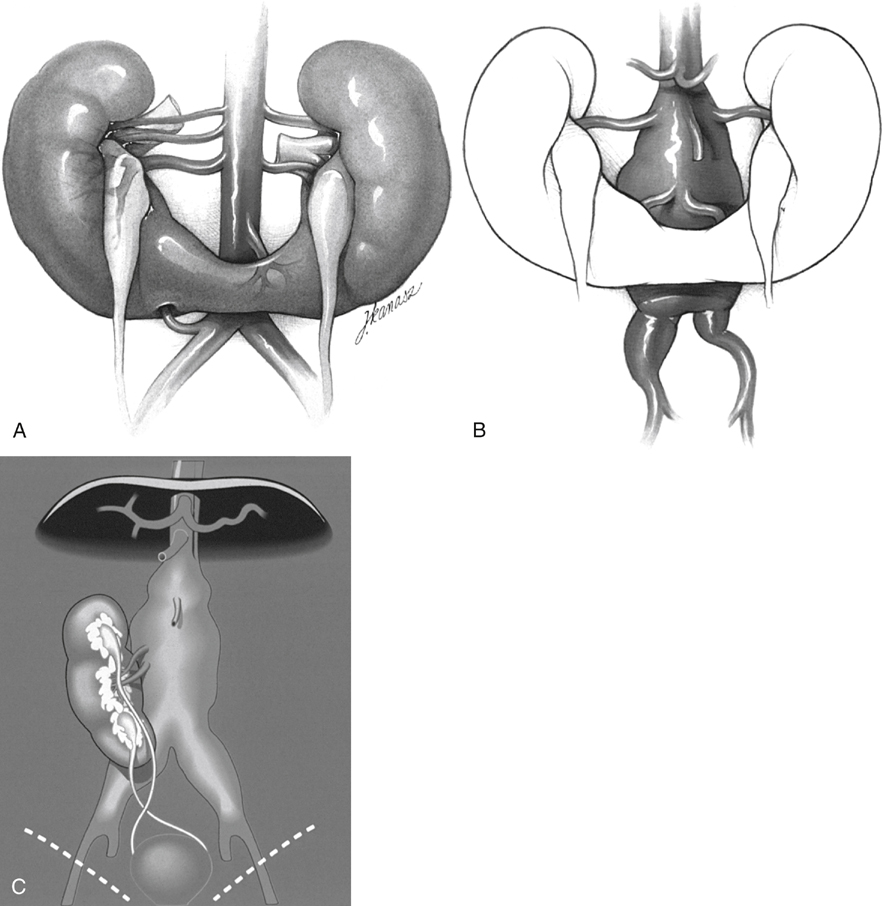

Developmental anomalies of the kidneys and upper urinary tracts may be categorized according to those leading to problems of number, ascent, rotation, or form and fusion of the renal parenchymal mass (Box 1). All may be associated with abnormalities in the renal vasculature as well as in the collecting system, but the problems with renal form and fusion are typically the most troublesome for the vascular surgeon during AAA repair. Anomalies of renal ascent or rotation alone rarely seriously interfere with traditional approaches to aortic reconstruction. In contrast, anomalies of fusion are usually associated with varying degrees of ectopia and malrotation, which can require modification of standard surgical techniques. Horseshoe kidney, thought to occur in 0.25% of the population, is probably the most common of all renal fusion abnormalities and is twice as common in men as it is in women. Horseshoe kidneys result when the metanephric masses fuse anteriorly in the midline. Their normal bilateral ascent is presumed to be blocked by the inferior mesenteric artery, and the associated impaired medial orientation causes the renal hila and collecting systems to be rotated ventrally, in turn inducing the ureters to lie anterior to the renal isthmus (Figure 1A). The horseshoe kidney usually consists of two separate renal masses lying vertically on either side of the midline and connected at their respective lower poles by an isthmus that crosses anterior to the aorta near the origin of the inferior mesenteric artery. This can pose a particular challenge during AAA repair (see Figure 1B). Although occasionally fibrous and avascular, the isthmus may consist of substantial renal parenchyma and its blood supply may be asymmetric, making simple division of the isthmus in the midline hazardous. Furthermore, the collecting systems may also be asymmetric and can extend anteriorly and across the midline in the region of the isthmus. Arterial and venous anomalies are common. If the fused metanephric masses ascend together on one side, in contrast to horseshoe kidney development, then crossed renal ectopia can result. In this anomaly, the ectopic kidney is located on the side contralateral to its ureterovesical junction and, in most instances, is fused to the inferior portion of the ipsilateral kidney (see Figure 1C). Fusion and crossover of the left kidney to the right side is the most common form of this variation and results in a single fused renal unit, with the collecting system lying anterior to the aorta and at least one of the ureters crossing the midline anterior to the aorta, usually above the second sacral vertebra. The arterial and venous anatomy often consists of multiple vessels in unpredictable locations. Crossed renal ectopia has been further classified depending on the shape assumed by the fused renal masses (see Box 1), but all forms are managed the same way during aortic reconstruction.

Renal Ectopia and Renal Fusion in Patients Requiring Abdominal Aortic Operations

Anatomic Subgroups of Renal Ectopia

Horseshoe Kidney

Crossed Renal Ectopia

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Thoracic Key

Fastest Thoracic Insight Engine