Renal Artery Fibromuscular Dysplasia

DAWN M. COLEMAN

Presentation

A 29-year-old woman carries a 12-month history of hypertension (HTN). She has been progressively managed medically by her primary care physician and is requiring three drugs presently. She presents with headaches of increasing frequency and intensity. Her review of systems is also notable for new dyspnea on exertion that has been progressive in nature. Exam reveals severe HTN (185/95), a right-sided abdominal bruit, and palpable femoral and dorsalis pedis pulses bilaterally.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for HTN in young adults is broad but should include essential HTN, endocrine dysfunction (i.e., pheochromocytoma, hyperaldosteronism, and hyperthyroidism), renal parenchymal disease, toxins/drugs (i.e., steroid, sympathomimetic drug, and cocaine use), central nervous system pathology and renovascular HTN from aortic coarctation, atheroemboli or renal artery stenosis secondary to atherosclerosis, vasculitis, or fibromuscular dysplasia (FMD). Additionally, given this patient’s history of dyspnea on exertion, cardiac dysfunction (and specifically hypertrophic cardiomyopathy) should be considered.

This patient’s young age (less than 30 years), three-drug antihypertensive regimen, and bruit should prompt consideration of secondary HTN, and specifically renovascular HTN secondary to renal FMD. Additional indications for diagnostic workup of secondary HTN include sudden acceleration of serum creatinine and HTN, increasing serum creatinine with the administration of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), worsening of previously well- controlled HTN, spontaneous hypokalemia, and unexplained (flash) pulmonary edema. Notably, HTN and headache are the most common FMD presenting symptoms, affecting 64% and 52% of patients, respectively, according to United States Registry for Fibromuscular Dysplasia. Interestingly, headaches are common among patients with isolated renal artery FMD despite well-controlled HTN.

Workup

Additional clinical history should elicit constitutional symptoms concerning for vasculitis and endocrine dysfunction, flank pain, hematuria, and relevant family history. Further symptoms of carotid, mesenteric, and lower extremity FMD might include tinnitus, dizziness, neck pain, flank/abdominal pain, postprandial abdominal pain, claudication, amaurosis fugax, Horner’s syndrome, and history of completed myocardial infarction or stroke.

A thorough clinical exam should assess for abdominal bruit, abdominal mass, peripheral pulses and pulse discrepancy across all four extremities, Horner’s syndrome (suggesting carotid dissection), neurologic deficit suggesting previous stroke, and a complete cardiopulmonary exam given concerns for hypertrophic cardiomegaly and possible heart failure.

Blood work should be sent to assess renal function (BUN, creatinine), vasculitis (C-reactive protein), and electrolyte levels. Additional blood hormone levels may help differentiate the diagnosis. Specifically, high plasma renin activity indicates renovascular HTN while altered aldosterone, thyroid, and catecholamine levels may indicate endocrine dysfunction. Urinalysis will reveal hematuria or azotemia, concerning for intrinsic renal disease.

Ultrasonography should be considered the first-line diagnostic imaging modality in patients with renovascular HTN. While a high-quality duplex ultrasound examination in an experienced center is extremely accurate for the diagnosis of main renal artery FMD, sensitivity is compromised when surveying branch or parenchymal renal arteries. Ultrasonography allows for determination of renal length and symmetry, the presence of main renal artery stenosis or aneurysm, and the resistive index.

Echocardiography should be performed to assess for left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and ventricular function. Computed tomography angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) are both useful adjunctive imaging modalities that will define better focal stenosis, aneurysms, renal infarcts, and dissections. CTA offers excellent spatial resolution, and generated three-dimensional multiplanar images can be very helpful in treatment planning for renal artery aneurysms. CTA, however, is limited in detecting subtle FMD lesions and branch vessel involvement. MRA is often favored in younger patients as it offers diagnostic sensitivity without the associated risks of irradiation.

Catheter-based arteriography remains the gold standard imaging modality for renovascular HTN given its unparalleled spatial resolution and ability to detect reliably branch vessel and parenchymal involvement. Additionally, pressure gradients can be measured across a stenosis (a systolic pressure gradient less than 10 mm Hg is considered normal), intravascular ultrasound may be used to further characterize the renal artery, and any clinically indicated therapeutic interventions can be performed in the same clinical setting.

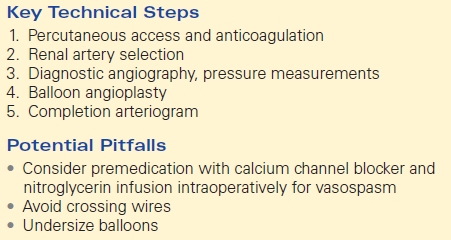

This patient’s electrolytes were normal and creatinine measured 0.7. Renal duplex ultrasound revealed a left renal longitudinal diameter of 11 cm and a right renal longitudinal diameter of 9 cm, a main right renal artery stenosis, and a resistive index of 0.56. Echocardiogram revealed mild LVH with preserved function. An arteriogram revealed alternating stenoses and dilation of the distal two thirds of the main right renal artery producing a “string of beads” appearance (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1 Classic arteriographic appearance of medial fibromuscular dysplasia—alternating stenoses and dilation affecting the distal two thirds of this main renal artery yield a “string of beads” appearance.

Diagnosis and Treatment

This patient has signs and symptoms of renovascular HTN secondary to medial FMD of the right main renal artery. FMD is a nonatherosclerotic, noninflammatory vascular disease that may result in arterial stenosis, occlusion, aneurysm, or dissection. FMD most commonly affects the renal arteries (58% to 75% of FMD cases) followed in frequency by the extracranial carotid and vertebral arteries (32%) and others (including iliac, mesenteric, and intracranial arteries). The prevalence of FMD in the general population remains unclear, but it is estimated that 4 in 100 adults are affected by renal FMD. Women are affected more commonly than men by a ratio of 9:1. The etiology remains poorly defined, although evolving data suggests a genetic basis for susceptibility to FMD.

Historically, FMD was classified histopathologically, with medial FMD being the most common histologic variant comprising greater than 90% of cases. Medial FMD includes the following variants: (1) medial fibroplasia (60% to 70%) characterized by deposition of loose collagen in zones of degenerating elastic fibrils in the media resulting in fibromuscular ridges (stenoses) alternating with areas of smooth muscle loss and consequent arterial dilation resulting in a classic “string of beads” angiographic appearance (as described above); (2) perimedial fibroplasia (15% to 25%) characterized by marked fibroplasia of the outer half of the media resulting in irregular luminal narrowing and smaller, less numerous “beads” (or dilated segments) in comparison to medial fibroplasia and obliteration of the elastic lamina; and (3) medial hyperplasia (5% to 15%) characterized by medial smooth muscle hyperplasia without significant collagen deposition such that arterial walls are otherwise well preserved. Intimal fibroplasia and adventitial disease are less common variants of FMD. Most recently, there has been a shift in the classification to radiographic that has been endorsed by the American Heart Association. Specifically, disease is characterized as multifocal (i.e., medial fibroplasia) or focal disease.

Treatment options for renal FMD include medical therapy with surveillance, endovascular therapy, and surgery. First-line antihypertensive agents include ACE inhibitors, ARBs, beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and diuretics. ACE inhibitors and ARBs are specifically effective for the treatment of renovascular HTN, and although acute renal insufficiency may occur with administration of renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system–modulating drugs, it is an uncommon complication of therapy and more often to occur in settings of bilateral renal artery stenosis and/or a sodium-depleted state.

This patient has resistant HTN with poorly controlled blood pressure and LVH despite three antihypertensive agents. Indications for renal artery revascularization in the setting of stenosis, dissection, and aneurysm include the following: (1) resistant HTN (failure to reach goal blood pressures in patients on an appropriate three-drug regimen that includes a diuretic); (2) HTN of short duration with the goal of a cure of HTN; and (3) preservation of renal function in a patient with severe stenosis. Percutaneous transluminal renal angioplasty (PTA) has become the treatment of choice for renovascular HTN secondary to FMD, although open surgical reconstructions should be considered for select cases of associated aneurysm, branch vessel disease, and failed PTA.

Surgical Approach—Percutaneous Transluminal Renal Angioplasty

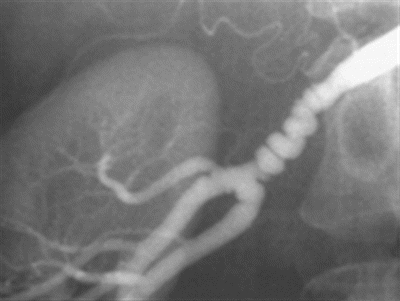

Percutaneous access of the common femoral, brachial, or radial artery should be performed with a micropuncture technique and ultrasound/fluoroscopic guidance. The patient is systemically anticoagulated with Heparin following sheath placement and prior to renal artery selection to decrease the risk of atheroembolism; an activated clotting time greater than 200 should be maintained throughout the procedure. Complete imaging should include aortogram and a full evaluation of the ostia, main renal artery, renal artery branches, and parenchyma of each kidney by way of selective renal arteriography in multiple angles. A trans-lesion pressure gradient evaluation by way of a 4-French catheter or 0.014-inch pressure wire passed into the renal artery will quantify the hemodynamic significance of a radiographic stenosis.

Angioplasty is performed through a guiding catheter or sheath placed at the ostium of the renal artery. Any wire size (0.014 to 0.035 inch) should support balloon delivery and placement across the lesion. Semi-compliant balloon selection is dictated by the diameter of adjacent normal vessel; cutting, scoring, and thermal balloons should be avoided. When the distal artery or its branches are affected, the use of multiple guide wires and a kissing balloon technique may be considered. Completion arteriography and pressure measurements should document procedural success. Primary stenting for renal FMD is not recommended (in contrast to renal atherosclerotic disease) given high rates of in-stent stenosis but may be considered for patients that fail balloon angioplasty or develop a flow-limiting dissection. Endovascular stent grafts may be considered for main renal artery aneurysms, and coil embolization may be considered for branch vessel aneurysms. Anticoagulation should be reversed with protamine prior to sheath removal and manual pressure maintained for hemostasis (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Percutaneous Transluminal Renal Angioplasty