Serum magnesium levels may be impacted by neurohormonal activation, renal function, and diuretics. The clinical profile and prognostic significance of serum magnesium level concentration in patients hospitalized for heart failure (HF) with reduced ejection fraction is unclear. In this retrospective analysis of the placebo group of the Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure Outcome Study with Tolvaptan trial, we evaluated 1,982 patients hospitalized for worsening HF with ejection fractions ≤40%. Baseline magnesium levels were measured within 48 hours of admission and analyzed as a continuous variable and in quartiles. The primary end points of all-cause mortality (ACM) and cardiovascular mortality or HF rehospitalization were analyzed using Cox regression models. Mean baseline magnesium level was 2.1 ± 0.3 mg/dl. Compared with the lowest quartile, patients in the highest magnesium level quartile were more likely to be older, men, have lower heart rates and blood pressures, have ischemic HF origin, and have higher creatinine and natriuretic peptide levels (all p <0.003). During a median follow-up of 9.9 months, every 1-mg/dl increase in magnesium level was associated with higher ACM (hazard ratio [HR] 1.77; 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.35 to 2.32; p <0.001) and the composite end point (HR 1.44; 95% CI 1.15 to 1.81; p = 0.002). However, after adjustment for known baseline covariates, serum magnesium level was no longer an independent predictor of either ACM (HR 0.94, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.28; p = 0.7) or the composite end point (HR 1.01, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.30; p = 0.9). In conclusion, despite theoretical concerns, baseline magnesium level was not independently associated with worse outcomes in this cohort. Further research is needed to understand the importance of serum magnesium levels in specific HF patient populations.

Magnesium, the second most common intracellular cation, plays an integral role in myocardial membrane function, enzymatic reactions, and intracellular transport. Investigations in chronic heart failure (HF) are conflicting regarding the prognostic role of varying magnesium levels in stable outpatients. Hypomagnesemia has been consistently linked to increased premature ventricular contractions and potentially increased arrhythmogenesis. The inpatient setting is marked by disturbances to magnesium homeostasis including diuretic therapy, heightened neurohormonal activation, impaired gastrointestinal absorption (secondary to gut edema), renal insufficiency, and poor nutritional intake. Data regarding the association between serum magnesium levels during hospitalization for HF and clinical outcomes are limited and generally inconsistent. In a small single-center study (n = 404), Cohen et al found that aberrations in serum magnesium levels (both hyper- and hypomagnesemia) at the time of hospitalization were associated with an increased postdischarge mortality. However, after adjustment for clinical variables, only low serum magnesium level retained prognostic utility. An Italian study with follow-up up to 3 years showed that hypermagnesemia was associated with increased mortality in elderly patients with HF. These incongruent data highlight the need for more robust and complete characterization of the clinical profiles and prognostic impact of serum magnesium levels during hospitalization for HF. The Efficacy of Vasopressin Antagonism in Heart Failure Outcome Study with Tolvaptan (EVEREST) dataset provides insight into the longitudinal electrolyte profiles in a large cohort of hospitalized patients with HF. Thus, we investigated the association between baseline serum magnesium levels and postdischarge outcomes in patients hospitalized for HF with reduced ejection fraction (EF).

Methods

The study design and primary results of the EVEREST trial have been previously published. In brief, EVEREST was a multicenter, international, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial evaluating tolvaptan, an oral vasopressin-2 receptor antagonist. The trial included patients hospitalized for HF with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class III or IV symptoms, EF of ≤40%, and signs and symptoms of fluid overload. Relevant exclusion criteria include a serum creatinine level of >3.5 mg/dl, serum potassium level of >5.5 mEq/L, and co-morbid conditions with life expectancy <6 months.

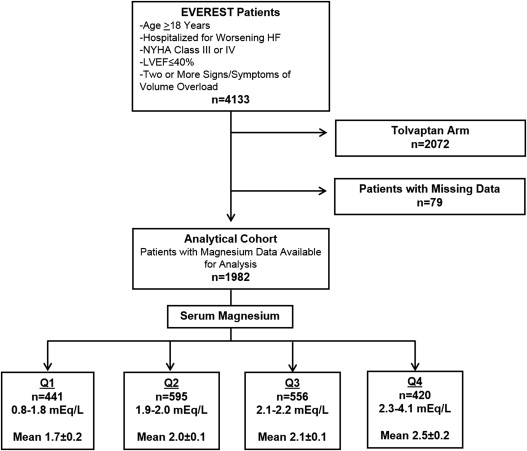

The ethics committee and institutional review board of each participating site approved the study protocol. After providing informed consent, the study participants were randomized to receive oral tolvaptan at a 30-mg fixed dose or matching placebo within 48 hours of hospital admission and was continued for at least 60 days. Concomitant medical therapies were left to the discretion of the treating physician. Because tolvaptan modestly increased serum magnesium levels as early as day 1 after randomization, this analysis was restricted to the placebo cohort. Laboratory samples were collected, processed, and cross-validated across 5 central facilities. Serum magnesium level (mg/dl) was measured at the time of study enrollment (baseline, up to 48 hours after admission) and every 4 to 8 weeks up to 112 weeks after discharge. Baseline magnesium level, expressed as a continuous function (per 1-mg/dl increase), was the primary predictor in this post hoc analysis. No nonlinear effects were detected; thus, no transformation of data was undertaken. However, for descriptive purposes, subjects were divided by magnesium level quartiles. The overall study design and final analytical cohort selection are displayed in Figure 1 .

Demographic characteristics, clinical history, signs and symptoms of HF, vital signs, laboratory parameters, and admission medications were compared across quartiles of baseline magnesium levels. An independent blinded adjudication committee determined the specific causes of death and reasons for rehospitalization. The present post hoc analysis used the same 2 coprimary end points as the overall EVEREST trial: all-cause mortality (ACM) and a composite end point of cardiovascular (CV) mortality or HF hospitalization. Secondary end points included other causes of death and rehospitalization, worsening HF (defined as death, hospitalization, or unplanned office visit for HF), and combined CV mortality and rehospitalization. Median follow-up was 9.9 months (interquartile range, 5.3 to 16.1 months).

Continuous variables are expressed as mean ± SD if normally distributed and median (interquartile range) if non–normally distributed. Categorical variables are expressed as number (percentage). Outcomes were assessed as time to first event using Cox proportional hazard models. Kaplan-Meier curves by serum magnesium level quartile were constructed for both primary end points and compared using log-rank tests. The proportional hazards assumption (by Kolmogorov-type supremum tests for nonproportionality) was upheld for both primary end points. Effect sizes were reported as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Multivariate models included 23 prespecified covariates including demographic characteristics (age, gender, and region of origin), clinical characteristics (ischemic HF origin, atrial fibrillation on admission electrocardiogram, coronary artery disease, diabetes, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease [CKD, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min/1.73 m 2 ], NYHA class IV, vital signs [supine systolic blood pressure], and laboratory and diagnostic testing [QRS duration on admission electrocardiogram, EF, serum sodium, serum potassium, blood urea nitrogen, B-type natriuretic peptide]), and baseline medication use (angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors or angiotensin II receptor blockers, β blockers, mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists, digoxin, and intravenous inotropes). Multiple imputation procedures (fully conditional specification method) were used to impute any missing covariate data (∼27% for natriuretic peptides, 4% for QRS duration, 2% for ischemic HF origin, and ≤1% for all other variables). No evidence of significant collinearity between baseline magnesium levels and the covariate set was detected (tolerance, 0.81). Separate interaction analyses were performed for CKD, diabetes, and ischemic HF origin. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina).

Results

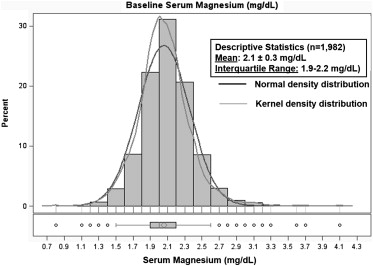

Of the 2,061 patients in the EVEREST placebo arm, 79 patients had missing serum magnesium levels at the time of enrollment. Serum magnesium level was normally distributed ( Figure 2 ) in the remaining analytical cohort (n = 1,982) with a mean of 2.1 ± 0.3 mg/dl, ranging from 0.8 to 4.1 mg/dl. Table 1 lists the baseline characteristics across magnesium level quartiles. Patients in the higher magnesium level quartiles tended to be older, men, and had lower presenting heart rates and systolic blood pressures (all p <0.003). Patients with higher magnesium levels also tended to have wider QRS durations on admission electrocardiogram and were more likely to have ischemic origin of HF and NYHA class IV symptoms (all p <0.003). Higher baseline magnesium level was associated with higher rates of CKD and higher initial serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen levels (all p <0.001). The only between-group medication difference was for digoxin, which was less commonly prescribed in the higher magnesium level quartiles (p = 0.003). Significant differences across quartiles were noted for diabetes, B-type natriuretic peptide levels, and serum sodium, but no clear trend was identified. Of note, no differences were observed in mean EF and signs and symptoms of HF across magnesium level quartiles.

| Characteristics | Magnesium Level Quartiles (mg/dl) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (0.8–1.8), n = 411 | Q2 (1.9–2.0), n = 595 | Q3 (2.1–2.2), n = 556 | Q4 (2.3–4.1), n = 420 | ||

| Magnesium level (mean ± SD) | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 2 ± 0 | 2.1 ± 0 | 2.5 ± 0.2 | <0.001 |

| Age (mean ± SD; yrs) | 63.4 ± 11.7 | 64.6 ± 11.9 | 66.6 ± 11.9 | 67.7 ± 12.5 | <0.001 |

| Men | 284 (69.1) | 449 (75.5) | 424 (76.3) | 336 (80) | 0.003 |

| Body mass index (median [IQR]; kg/m 2 ) | 28.6 (24.7–32.5) | 27.4 (24.3–31.9) | 27.8 (24.7–32.3) | 28.0 (24.6–31.2) | 0.336 |

| Ejection fraction (mean ± SD; %) | 27.3 ± 8.3 | 28 ± 8 | 27.9 ± 8.3 | 26.9 ± 8.2 | 0.118 |

| QRS duration (mean ± SD; ms) | 120.6 ± 31.9 | 122.6 ± 32.4 | 127.4 ± 35.3 | 137.3 ± 38.2 | <0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation or flutter | 133 (32.4) | 172 (29) | 160 (28.8) | 107 (25.5) | 0.188 |

| Ischemic origin of HF | 252 (62.5) | 368 (62.4) | 370 (67.5) | 301 (72.5) | 0.003 |

| NYHA class IV | 185 (45) | 234 (39.3) | 184 (33.2) | 189 (45.1) | <0.001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 278 (68) | 406 (68.4) | 397 (71.4) | 315 (75) | 0.076 |

| Hypertension | 296 (72) | 432 (72.6) | 389 (70) | 298 (71) | 0.776 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 179 (43.8) | 267 (45.1) | 266 (48) | 225 (53.7) | 0.017 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 185 (45) | 210 (35.3) | 196 (35.3) | 153 (36.4) | 0.006 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 76 (18.5) | 123 (20.7) | 156 (28.1) | 183 (43.6) | <0.001 |

| Dyspnea | 360 (88.7) | 536 (91.5) | 506 (92.3) | 376 (91.5) | 0.243 |

| Jugular venous distension | 118 (29.4) | 138 (23.8) | 142 (26.2) | 122 (29.8) | 0.108 |

| Rales | 329 (81) | 476 (81.2) | 449 (81.8) | 343 (83.3) | 0.833 |

| Pedal edema ∗ | 325 (79.9) | 459 (78.3) | 442 (80.5) | 333 (80.8) | 0.746 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mean ± SD; mm Hg) | 121.5 ± 19.3 | 122.7 ± 19.6 | 120.3 ± 19.5 | 115.6 ± 18.4 | <0.001 |

| Heart rate (mean ± SD; beats/min) | 82.5 ± 16.3 | 80.3 ± 15.8 | 78 ± 14.6 | 78.2 ± 15.5 | <0.001 |

| Albumin (mean ± SD; g/dl) | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | 3.8 ± 0.5 | <0.001 |

| B-type natriuretic peptide (median [IQR]; pg/ml) † | 789 (392–1,594) | 675 (301–1,417) | 631 (272–1,417) | 890 (372–1,860) | 0.008 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mean ± SD; g/dl) | 25.1 ± 11.8 | 26 ± 11.5 | 30.7 ± 15.3 | 41.5 ± 23.1 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mean ± SD; mg/dl) | 1.2 ± 0.4 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.7 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Serum sodium (mean ± SD; mEq/L) | 138.9 ± 4.5 | 139.8 ± 4.3 | 140 ± 4.8 | 139.7 ± 5.4 | 0.006 |

| Baseline medications | |||||

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 355 (86.6) | 505 (85.3) | 470 (84.8) | 337 (80.2) | 0.059 |

| Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist | 234 (57.1) | 337 (56.9) | 292 (52.7) | 228 (54.3) | 0.419 |

| β blocker | 288 (70.2) | 406 (68.6) | 398 (71.8) | 294 (70) | 0.692 |

| Digoxin | 227 (55.4) | 294 (49.7) | 268 (48.4) | 179 (42.6) | 0.003 |

| Diuretics | 401 (97.8) | 573 (96.8) | 537 (96.9) | 410 (97.6) | 0.720 |

| Statins | 127 (31) | 182 (30.7) | 196 (35.4) | 155 (36.9) | 0.100 |

∗ Peripheral edema was defined as slight, moderate, or marked pedal or sacral edema.

† B-type natriuretic peptide data are available for 270, 436, 418, and 313 patients for Q1 to 4, respectively.

During a median follow-up of 9.9 months, 524 placebo patients experienced ACM, whereas 797 experienced the composite end point of CV mortality or HF hospitalization ( Table 2 ). Rates of ACM increased from 22.9% in quartile 1 to 33.3% in quartile 4 of baseline magnesium levels (p = 0.003). Similarly, rates of the composite outcome increased from 36.3% to 44.5% across the 4 quartiles (p = 0.074). Analysis of secondary outcomes revealed significant increases in rates of CV mortality (p = 0.005), HF mortality (p <0.001), worsening HF (p = 0.006), and combined CV mortality and rehospitalization (p = 0.032), with increased serum magnesium level quartiles. Other secondary outcomes did not significantly differ by magnesium level quartile. Times to first event were also significantly different by the Kaplan-Meier method across magnesium level quartiles for ACM ( Figure 3 ; log-rank p <0.001) and CV mortality or HF hospitalization ( Figure 3 ; log-rank p = 0.004).

| Characteristics | Magnesium Level Quartiles (mg/dl) | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 (0.8–1.8), n = 411 | Q2 (1.9–2.0), n = 595 | Q3 (2.1–2.2), n = 556 | Q4 (2.3–4.1), n = 420 | ||

| Primary end points | |||||

| ACM | 94 (22.9) | 146 (24.5) | 144 (25.9) | 140 (33.3) | 0.003 |

| CV mortality and HF hospitalization | 149 (36.3) | 230 (38.7) | 231 (41.5) | 187 (44.5) | 0.074 |

| Causes of death | |||||

| CV | 69 (16.8) | 113 (19) | 105 (18.9) | 109 (26) | 0.005 |

| Sudden cardiac death | 26 (6.3) | 43 (7.2) | 37 (6.7) | 23 (5.5) | 0.733 |

| HF | 28 (6.8) | 55 (9.2) | 55 (9.9) | 77 (18.3) | <0.001 |

| Myocardial infarction | 5 (1.2) | 3 (0.5) | 3 (0.5) | 4 (1) | 0.527 |

| Stroke | 3 (0.7) | 3 (0.5) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 0.529 |

| Other CV | 7 (1.7) | 9 (1.5) | 9 (1.6) | 4 (1) | 0.795 |

| Non-CV | 17 (4.1) | 20 (3.4) | 21 (3.8) | 19 (4.5) | 0.805 |

| Reasons for rehospitalization | |||||

| CV | 140 (34.1) | 213 (35.8) | 228 (41) | 168 (40) | 0.080 |

| HF | 100 (24.3) | 157 (26.4) | 162 (29.1) | 121 (28.8) | 0.320 |

| Myocardial infarction | 8 (1.9) | 7 (1.2) | 8 (1.4) | 6 (1.4) | 0.799 |

| Stroke | 4 (1) | 5 (0.8) | 6 (1.1) | 3 (0.7) | 0.939 |

| Arrhythmia | 11 (2.7) | 17 (2.9) | 13 (2.3) | 15 (3.6) | 0.713 |

| Other CV | 17 (4.1) | 27 (4.5) | 39 (7) | 23 (5.5) | 0.170 |

| Worsening HF ∗ | 127 (30.9) | 198 (33.3) | 214 (38.5) | 172 (41) | 0.006 |

| CV mortality and rehospitalization | 178 (43.3) | 257 (43.2) | 273 (49.1) | 213 (50.7) | 0.032 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree