The present research examined optimism’s relation with total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, and triglycerides. The hypothesis that optimism is associated with a healthier lipid profile was tested. The participants were 990 mostly white men and women from the Midlife in the United States study, who were, on average, 55.1 years old. Optimism was assessed by self-report using the Life Orientation Test. A fasting blood sample was used to assess the serum lipid levels. Linear and logistic regression models examined the cross-sectional association between optimism and lipid levels, accounting for covariates such as demographic characteristics (e.g., education) and health status (e.g., chronic medical conditions). After adjusting for covariates, the results suggested that greater optimism was associated with greater high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and lower triglycerides. Optimism was not associated with low-density lipoprotein or total cholesterol. The findings were robust to a variety of modeling strategies that considered the effect of treatment of cholesterol problems. The results also indicated that diet and body mass index might link optimism with lipids. In conclusion, this is the first study to suggest that optimism is associated with a healthy lipid profile; moreover, these associations can be explained, in part, by the presence of healthier behaviors and a lower body mass index.

The present study investigated a cardiovascular risk factor that has yet to be empirically investigated in relation to optimism—namely, serum lipids. Optimism and lipid levels were expected to be associated because lipid profiles are driven in part by health behaviors and optimism has been linked to healthier behaviors, such as eating a balanced diet, exercising, and consuming moderate amounts of alcohol. We hypothesized that greater levels of optimism would be associated with a healthier lipid profile (i.e., more high-density lipoprotein [HDL] cholesterol and less total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein [LDL] cholesterol, and triglycerides), controlling for potential confounders (i.e., demographic characteristics and health status). Moreover, we hypothesized that the association between optimism and the lipid levels would be partially explained by healthier behaviors, such as moderate alcohol consumption, exercise, diet, and the absence of cigarette smoking. To investigate these hypotheses, we conducted cross-sectional analyses of data from men and women included in the Midlife in the United States (MIDUS) study.

Methods

The MIDUS study was started in 1995 to better understand the connections among psychosocial factors, aging, and health in men and women aged 25 to 74 years. More than 4,000 subjects were first recruited by either random digit dialing or oversampling select metropolitan areas. Twin pairs and ≥1 siblings of randomly selected participants were recruited when possible, resulting in a total baseline sample of 7,108. A longitudinal follow-up assessment comprised of 5 distinct projects was initiated 9 to 10 years later. The present investigation included a subsample of respondents from the longitudinal follow-up who had completed the psychosocial and biomarker projects. The psychosocial project, which entailed a telephone interview and self-administered questionnaires, was completed by 5,895 of the original 7,108 participants and included measures of optimism and demographic factors. The participants who completed the psychosocial project and who were healthy enough to travel to a research clinic were eligible for the biomarker project, which was conducted an average of 26 ± 14.66 (SD) months later (range 2 to 62). The biomarker project was an in-depth, multiday assessment with an overnight stay that yielded measures of lipids, health status, and health behaviors, among others. Because of the substantial commitment required, 1,255 of the 3,191 eligible men and women (39.3%) participated (43.1% participated after adjusting for those who could not be contacted or located). Of the eligible participants, those who participated in the biomarker project did not differ from those who did not with regard to age, gender, race, marital status, income, chronic disease, or body mass index (BMI), but they were more highly educated. Only participants with complete data on optimism, lipid levels, potential confounders, and pathway variables were included, yielding an analytic sample of 990. The appropriate institutional review boards approved the present research, and all participants provided consent.

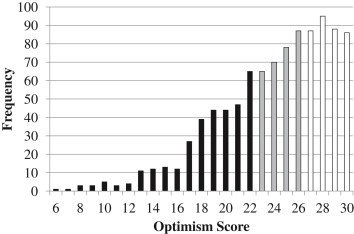

The 6-item Life Orientation Test-Revised was used to assess optimism. The participants indicated the extent to which they agreed (1, agree a lot; to 5, disagree a lot) with 3 positively worded items (“I expect more good things to happen to me than bad,” “I’m always optimistic about my future,” “In uncertain times I usually expect the best”) and 3 negatively worded items (“I hardly ever expect things to go my way,” “If something can go wrong for me it will,” “I rarely count on good things happening to me”). Because optimism can best be characterized by endorsing both positively worded items and rejecting negatively worded items, we followed the recommendations to use the 6-item composite rather than the 3-item subscales. The positively worded items were reverse scored and added to negatively worded items to create a total optimism score ranging from 6 to 30 ( Figure 1 ; α = 0.82). Higher values indicated more optimism, and the total score was standardized (mean 0 ± 1) for greater interpretability.

The participants traveled to 1 of 3 clinical research sites for 2 days of biologic assessment. On the second morning of the visit, the participants provided a fasting blood sample for a lipid panel of total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and triglycerides. The samples were initially stored in a −60°C to −80°C freezer at each site, and then frozen serum (1-ml aliquots) was shipped on dry ice to Meriter Laboratories (Madison, Wisconsin) and stored at −65°C. All assays were performed with a Cobas Integra analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, Indiana). An enzymatic colorimetric assay was used for total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and triglycerides; LDL cholesterol was derived using the Friedewald calculation (if the triglyceride levels were >400 mg/dl, the observed values were replaced with 400 mg/dl to calculate the LDL cholesterol level). From the total biomarker project sample, the total cholesterol assays ranged from 0 to 800 mg/dl (reference range <200); the interassay coefficient of variation (CV) was 1.4% to 1.9% and the intra-assay CV 0.5% to 0.8%. The HDL cholesterol assays ranged from 0 to 155 mg/dl (reference range 40 to 85); the interassay CV was 2.2% to 2.3% and intra-assay CV 1.1% to 1.5%. The triglyceride assays ranged from 0 to 875 mg/dl (reference range <150); the interassay CV was 1.9% and intra-assay CV 1.6%. The LDL cholesterol interassay CV was 10.11% (reference range 60 to 129 mg/dl).

The analyses were controlled for factors known to be associated with the lipid profiles. The demographic data were self-reported and included age (in years), gender, race (white, nonwhite), education (less than high school degree, high school degree, some college, college degree or greater), household income, and months between the optimism and serum lipid assessments. Health status included chronic conditions (none or ≥1 condition) and blood pressure medication use (no, yes). The presence of chronic conditions (heart disease, hypertension, stroke, or diabetes) was assessed by the item “Have you ever had any of the following conditions or illnesses diagnosed by a physician?” Corticosteroids and depression medications were also considered but were not included in the final models because they were not associated with lipids in the age-adjusted regression analyses. The categorical variables were dummy coded before inclusion in the models.

To examine optimism’s independent effects from psychological ill-being, negative affect was controlled in the secondary analyses. Negative affect was assessed during the psychosocial project using 5 items from a widely used and psychometrically valid scale. The participants indicated the extent to which they felt afraid, jittery, irritable, ashamed, and upset in the previous 30 days (1, none of the time; to 5, all of the time). In accordance with previous work in the MIDUS study, an average score was calculated if ≥1 item was rated; higher scores reflected more negative affect.

Potential behavioral pathways included smoking status (current smoker, past smoker, never smoker), average number of drinks consumed/day in the past month, regular exercise ≥3 times/week for 20 minutes (no, yes), and prudent diet. Smoking status and exercise were dummy coded for statistical analysis. For diet, the participants indicated their consumption of food categories during an average day or week. Consistent with previous research, a prudent diet score was calculated by giving the participants a point for consuming ≥3 servings/day of fruit and vegetables, ≥3 servings/day of whole grains, ≥1 servings/week of fish, ≥1 servings/week of lean meat, no sugared beverages, ≤2 servings/week of beef or high-fat meat, and food at a fast food restaurant less than once per week. The scores ranged from 0 to 7 (mean 4.24 ± 1.39); higher scores indicated a healthier diet. Because BMI is a product of health behaviors and genetics, we also investigated its potential role as a mediator. BMI was measured by the clinical staff during the biologic assessment.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Given that treatment of cholesterol problems could bias the findings, previous work has routinely excluded participants who were receiving treatment. However, such an approach is not recommended because it discards relevant information, reduces power, and biases the parameter estimates. Thus, in accordance with previous research, the lipid levels of those participants who were taking cholesterol medicine (n = 284) were corrected for the typical effect of such treatment. That is, we increased the levels of total cholesterol by 20%, LDL cholesterol by 35%, and triglycerides by 15% and decreased the levels of HDL cholesterol by 5%. Because the distribution of triglyceride scores was skewed and kurtotic, the triglyceride scores were log transformed. The total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, and LDL cholesterol levels had approximately normal distributions and were not transformed.

Each lipid served as an outcome in a series of linear regression models. The minimally adjusted model included demographic data (i.e., age, gender, race, education, income, and interval between the psychosocial and biologic assessments) and optimism as predictors. A second multivariable-adjusted model added health status (i.e., chronic conditions and blood pressure medication) to the first model. Sensitivity analyses examined whether the results differed when the (1) original lipid scores for all participants were maintained, regardless of the use of cholesterol medication (an approach in which the associations might be biased because of treatment), (2) participants taking cholesterol medication were excluded, and (3) the use of cholesterol medication was included as a covariate.

Additional models examined whether health behaviors and BMI were on the pathway between optimism and lipid levels in minimally adjusted models. However, because all data for relevant covariates were cross-sectional, we did not formally test mediation; thus, the direction of effects could be reversed. Instead, we examined how the regression coefficient for optimism changed when it was the sole predictor versus when a potential pathway variable was added to the model. When the regression coefficient for optimism was reduced (indicated by a change of ≥10%) with the addition of a potential pathway variable, this suggested that the pathway variable partly explained optimism’s association with lipids.

In the secondary analyses, negative affect was controlled for in the minimally adjusted models and also used to stratify the minimally adjusted models. We also conducted logistic regression analyses for each lipid to determine whether optimism was associated with the probability of being at high risk of unhealthy lipid levels (defined as taking cholesterol medication, diagnosis by a physician of cholesterol problems, or exceeding conventional cutpoints for having high [or in the case of HDL cholesterol, low] lipid levels). To account for the clustering of data because of the presence of sibling and twin pairs in the cohort, we reran the primary statistical analyses using generalized estimating equations. When the primary statistical analyses were conducted with generalized estimating equations, the results were nearly identical to those described. This suggested that the presence of clustering in the analytic sample did not bias the parameter estimates or standard errors. In the interest of interpretability, we have presented the findings from the primary statistical analyses. We also examined whether the association between optimism and lipid levels differed by race, but no differences were evident (data not shown).

Results

The participants were on average 55.12 ± 11.78 years old (range 34 to 84). Men constituted 45% of the sample (n = 449) and women 55% (n = 541). The vast majority was white (93%; n = 923). The average lipid level was 196.62 ± 38.00 mg/dl (first quartile 171.00; second quartile 194.40; third quartile 218.40) for total cholesterol, 54.08 ± 17.63 mg/dl (first quartile 41.00; second quartile 51.64; third quartile 64.21) for HDL cholesterol, and 115.41 ± 35.28 mg/dl (first quartile 91.12; second quartile 111.75; third quartile 136.00) for LDL cholesterol. The average triglyceride level was 135.42 ± 82.12 (first quartile 81.00; second quartile 113.85; third quartile 166.00) before transformation. The distribution of covariates according to optimism level and correlations between optimism and covariates are listed in Tables 1 and 2 . More optimistic subjects tended to be older, have greater education levels and income, engage in healthier behaviors, and report less negative affect compared to their less optimistic peers.

| Characteristic | Optimism | p ∗ | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (n = 334) | Moderate (n = 300) | High (n = 356) | ||

| Age (yrs) | 53.13 ± 11.68 | 56.58 ± 12.36 | 55.75 ± 11.15 | 0.0005 |

| Gender | 0.33 | |||

| Male | ||||

| Column % | 48.50 | 44.67 | 42.98 | |

| Row % | 36.08 | 29.84 | 34.08 | |

| Female | ||||

| Column % | 51.50 | 55.33 | 57.02 | |

| Row % | 31.79 | 30.68 | 37.52 | |

| Race | 0.24 | |||

| White | ||||

| Column % | 91.62 | 95.00 | 93.26 | |

| Row % | 33.15 | 30.88 | 35.97 | |

| Nonwhite | ||||

| Column % | 8.38 | 5.00 | 6.74 | |

| Row % | 41.79 | 22.39 | 35.82 | |

| Education | <0.0001 | |||

| Less than a high school degree | ||||

| Column % | 5.69 | 2.33 | 2.53 | |

| Row % | 54.29 | 20.00 | 25.71 | |

| High school degree | ||||

| Column % | 26.05 | 21.00 | 15.17 | |

| Row % | 42.65 | 30.88 | 26.47 | |

| Some college | ||||

| Column % | 32.34 | 28.67 | 25.56 | |

| Row % | 37.89 | 30.18 | 31.93 | |

| College degree or more | ||||

| Column % | 35.93 | 48.00 | 56.74 | |

| Row % | 25.75 | 30.90 | 43.35 | |

| Income (United States dollars in thousands) | 68.11 ± 54.32 | 75.58 ± 57.97 | 85.87 ± 65.12 | 0.0004 |

| Interval between assessments (mo) | 25.91 ± 14.64 | 26.15 ± 14.73 | 26.39 ± 14.66 | 0.91 |

| Chronic conditions | 0.74 | |||

| Yes | ||||

| Column % | 42.22 | 44.00 | 41.01 | |

| Row % | 33.65 | 31.50 | 34.84 | |

| No | ||||

| Column % | 57.78 | 56.00 | 58.99 | |

| Row % | 33.80 | 29.42 | 36.78 | |

| Blood pressure medication | 0.64 | |||

| Yes | ||||

| Column % | 33.83 | 37.00 | 33.99 | |

| Row % | 32.75 | 32.17 | 35.07 | |

| No | ||||

| Column % | 66.27 | 63.00 | 66.01 | |

| Row % | 34.26 | 29.30 | 36.43 | |

| Body mass index (kg/m 2 ) | 29.71 ± 6.60 | 28.76 ± 5.51 | 28.91 ± 5.85 | 0.10 |

| Smoking status | <0.0001 | |||

| Current | ||||

| Column % | 17.66 | 9.00 | 7.30 | |

| Row % | 52.68 | 24.11 | 23.21 | |

| Past | ||||

| Column % | 30.24 | 36.33 | 31.74 | |

| Row % | 31.27 | 33.75 | 34.98 | |

| Never | ||||

| Column % | 52.10 | 54.67 | 60.96 | |

| Row % | 31.35 | 29.55 | 39.10 | |

| Alcohol consumption (drinks/day) | 1.34 ± 1.40 | 1.10 ± 1.23 | 1.15 ± 1.39 | 0.06 |

| Prudent diet | 3.90 ± 1.45 | 4.29 ± 1.32 | 4.51 ± 1.33 | <0.0001 |

| Regular exercise | 0.008 | |||

| Yes | ||||

| Column % | 74.25 | 84.00 | 80.62 | |

| Row % | 31.51 | 32.02 | 36.47 | |

| No | ||||

| Column % | 25.75 | 16.00 | 19.38 | |

| Row % | 42.36 | 23.65 | 33.99 | |

| Negative affect | 1.76 ± 0.61 | 1.48 ± 0.43 | 1.35 ± 0.34 | <0.0001 |

| Total cholesterol | 198.15 ± 38.06 | 195.55 ± 38.29 | 196.08 ± 37.77 | 0.65 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 52.29 ± 17.64 | 53.48 ± 16.55 | 56.26 ± 18.30 | 0.01 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol | 118.07 ± 35.55 | 114.42 ± 35.35 | 113.74 ± 34.93 | 0.23 |

| Triglycerides † | 140.53 ± 86.62 | 137.99 ± 88.74 | 128.47 ± 70.99 | 0.13 |

∗ p Values from chi-square or analysis of variance tests.

| Characteristic | Association With Optimism | |

|---|---|---|

| r | p | |

| Age | 0.18 | <0.0001 |

| Gender ∗ | 0.02 | 0.49 |

| Race † | −0.04 | 0.21 |

| Education ‡ | 0.18 | <0.0001 |

| Income | 0.14 | <0.0001 |

| Interval between assessments | 0.01 | 0.71 |

| Chronic conditions § | 0.003 | 0.93 |

| Blood pressure medication || | 0.03 | 0.43 |

| Body mass index | −0.07 | 0.03 |

| Smoking status ¶ | 0.13 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | −0.07 | 0.03 |

| Prudent diet | 0.21 | <0.0001 |

| Regular exercise # | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| Negative affect | −0.45 | <0.0001 |

† Race: white = 0, nonwhite = 1.

‡ Education: less than high school degree = 1, high school degree = 2, some college = 3, college degree or more = 4.

§ Chronic conditions: no = 0, yes = 1.

‖ Blood pressure medication: no = 0, yes = 1.

¶ Smoking status: 1 = current smoker, 2 = past smoker, 3 = never smoker.

Optimism was not associated with LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol levels but was associated with HDL cholesterol and triglycerides in the expected directions ( Table 3 ). For each SD increase in optimism, the HDL cholesterol levels were >1 mg/dl greater. For each SD increase in optimism, the triglyceride levels were 3% lower. These findings were only modestly attenuated after multivariable adjustment.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree