36 Regional Centers of Excellence for the Care of Patients with Acute Ischemic Heart Disease

The past decade has witnessed a remarkable evolution both in our understanding of the pathogenesis of ACS and in therapeutic innovation for catheter-based technologies and adjunctive pharmacotherapies. Spontaneous plaque rupture is followed by platelet adherence, activation, and aggregation, with fibrin incorporation leading to thrombus propagation.1 The severity of the resultant clinical syndrome is manifest in direct proportion to the degree of restriction in coronary blood flow and ranges from asymptomatic (insignificant restriction) to non–ST elevation ACS (NSTEACS), including unstable angina and non–ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), which are associated with severe coronary flow restriction, as well as STEMI, which is usually secondary to complete coronary occlusion.2 As the pathogenesis of coronary flow restriction is multi-factorial (platelets, thrombus, vasomotion, and mechanical obstruction), it is best addressed by a multi-modal approach to therapy (anti-platelet, anticoagulant, and fibrinolytic therapies and catheter-based PCI) implemented in a timely manner. Indeed, the rapid restoration of normal coronary blood flow—via pharmacologic and mechanical recanalization of an occluded coronary artery—limits the extent of myocardial necrosis and reduces mortality. However, a concerted, integrated approach to the therapy for ACS is complicated by the diversity and extent of resources required for the comprehensive treatment of this disease spectrum and by the various settings (urban/suburban and rural) in which care is delivered. The concept of regional centers of excellence for the care of patients with ACS has rapidly evolved and has become the focus of a collaborative initiative involving the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology as well as individual states which have been charged with regional organization. It is important to clearly define “regional” so that all of the constituents involved in the care of patients with ACS understand the concept and the implications. The term regional implies meaningful networking associations between community hospitals, rural hospitals, or both, which do not provide tertiary cardiovascular services (including PCI), and a tertiary cardiovascular service provider. The definition of “meaningful networking” includes, at one end of the spectrum, being a merged affiliate (same hospital system) and, at the other, merely sharing common protocols for patient care as well as tracking, auditing, and reporting clinical practice guideline compliance, core measures, and clinical outcomes. These “networks” should have well-defined and rehearsed systems for patient transport that will differ, depending on care being delivered in an urban, suburban, or rural setting.

Scope of the Problem

Scope of the Problem

The approach of creating specialized centers of care for treating victims of trauma and, more recently, stroke has been shown to improve clinical outcomes.3 Trauma victims treated in trauma centers had significantly lower mortality compared with patients treated in a non–trauma center. Specialized centers for the care of patients who had suffered a stroke have been instituted with the standard of care established by the American Heart Association and with a formal process provided through the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) for the certification of primary stroke centers.4 Interestingly, the number of deaths from CAD in the United States alone exceeds sevenfold the number for all-cause trauma and fourfold that for stroke in the general population; the number of deaths is twentyfold and fivefold higher for trauma and stroke, respectively, for persons older than 65 years.5 In addition, of the 865,000 new or recurrent heart attacks which occurred in the United States (U.S.) during 2003, 35% to 40% were attributed to STEMI.6 In this context, the number of specialized regional centers of care for patients with acute ischemic heart disease is not commensurate with the magnitude of this public health problem.

The Case for Regionalized Care

The Case for Regionalized Care

Both where and how patients with acute ischemic heart disease are treated has been the subject of an ongoing debate. The divergence of opinion ranges from belief that “the real issue is not whether the creation of specialized centers for care of ACS patients would provide an important advance, but how to create them,” to the contention that “clear, compelling evidence of the benefits of ACS regionalization within the United States and a better understanding of its potential consequences are needed before implementing a national policy of regionalized ACS care.”7–11

Proponents assert that the treatment of patients with ACS at regional centers with dedicated facilities will save lives by providing higher-quality care and by improving access to new technologies as well as to specialist physicians.7–9 These beliefs are, in large part, based on prior experiences with regard to trauma and stroke treatments in the United States as well as on experiences gleaned from multiple European countries, where regionalized systems for ACS care are in place.12–14 Although efficiency of process and high quality of outcomes have been demonstrated in several European systems, the “generalizability” of these data to current practice in the United States has been questioned.10,11 As European health systems are characterized by centralized financing as well as control of hospital and emergency transportation organizations, they avoid many of the financial reimbursement “barriers” present in the U.S. health care system. Furthermore, the logistics of providing regionalized care in the United States, where the population is more geographically dispersed, present additional challenges. Nevertheless, several states and municipalities have initiated programs for the regionalized care of patients with ACS.15 The American Heart Association (AHA), in conjunction with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), has initiated a national program (Mission : Lifeline) to provide timely primary PCI to more patients with STEMI and to create both systems and centers of care, with the goal of reducing deaths from CAD and stroke by 25% by the year 2010.16 These initiatives have been, in part, prompted by recent studies that demonstrated shortfalls in the use of quality-assured, guideline-driven care for patients with ACS as well as wide variability in treatments administered on the basis of age, gender, race, geographic location, and time of presentation.17–19

A treatment–risk “paradox” has, indeed, been demonstrated with regard to the use of both proven, guideline-based medical therapies (specifically early administration of thienopyridines, platelet glycoprotein [GP] IIb/IIIa inhibitors, or both) and early angiography and coronary revascularization in patients who present with NSTEACS.20,21 Although randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that the benefit of an early invasive treatment strategy in NSTEACS is directly proportional to patient risk profile, the propensity to receive such treatment has been greatest in those patients at lower risk. Similarly, treatment with clopidogrel, platelet GP IIb/IIIa inhibitors, or both, in addition to transfer for angiography at a non–PCI capable facility, is inversely proportional to patient risk strata.22–24 This observation may have arisen from physician misconceptions about benefit–harm tradeoffs or concerns about treatment complications. Indeed, one analysis suggests that at least 25% of opportunities to initiate guideline-based care are missed in contemporary community practice.25 Finally, the process of care for patients with ACS has been further complicated by the fact that for many U.S. hospitals, the provision of treatment for CAD is the major determinant of their financial well-being. Profitability from a cardiovascular service line is often used to offset deficits incurred by the provision of other important but less profitable services such as mental health, obstetrics, and emergency medicine.16

Potential Advantages of Regional Centers

Potential Advantages of Regional Centers

Practice Makes Perfect: Relationship between Volume and Outcomes

In general, a patient experiences a better clinical outcome when treated in a center that frequently encounters the particular health problem that the patient has (“Practice makes perfect”).26,27 A direct relationship has been demonstrated between physician–operator as well as facility procedural volumes and optimal clinical outcomes with both elective or primary PCI and coronary bypass surgery.28–32 A similar relationship has been demonstrated between hospital ACS patient volume and clinical outcomes as well as adherence to ACC/AHA guidelines.33,34 Doctors and hospitals performing the highest volumes of procedures demonstrate the best clinical outcomes, including survival benefit. Higher-volume PCI centers demonstrate lower risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality as well as less frequent need for emergency coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), even in the current era of coronary stenting.31,32,35 Indeed, the relative benefit of primary PCI versus fibrinolysis for the treatment of STEMI may be completely lost when primary PCI is performed in a low-volume institution.28,36 Data from the New York statewide database demonstrate that physician–operator volume significantly influences the success rate of primary PCI procedures and that hospital volume influences (by 50%) in-hospital mortality following the procedure.37 These observations have led to the belief that PCI “generally should not be conducted in low-volume hospitals unless there are substantial overriding concerns about geographic or socioeconomic access” and to recommendations for hospitals performing primary PCI for STEMI to satisfy specific minimum requirements for volume of procedures.30,38

A pooled analysis of multiple studies involving over one million PCI procedures confirms the relationship between lower procedural volumes (<200 cases) with an increase in both in-hospital mortality and the requirement for emergency CABG following PCI.32 Other studies have suggested that institutional volumes more than 200 cases yearly may be too low. For example, an analysis of 37,848 PCI procedures, performed at 44 centers in 2001–2002 as part of the Greater Paris area PTCA (percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty) registry, demonstrated an increased incidence of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACEs) following elective as well as primary PCI procedures in centers performing less than 400 procedures yearly.35 In addition, in-hospital mortality increased following primary PCI procedures in lower-volume (<400 PCI/year) programs. These investigators concluded that “tolerance of low-volume thresholds for angioplasty centers with the purpose of providing primary PCI in acute myocardial infarction should not be recommended, even in underserved areas.”11,35 More recently, the relationship between institutional volume and clinical outcomes has been demonstrated in centers providing primary PCI without on-site cardiac surgical facilities. No differences in outcomes were observed in the ACC-NCDR (National Cardiovascular Data Registry) among primary PCI centers stratified on the basis of cardiac surgical capability (with vs. without).39 However, a significant reduction in risk-adjusted mortality was observed in the highest tertile of primary PCI institutional volume (mean, 83 processes per year) among centers without surgical capability in C-PORT (Community Hospital–Based, Prospective, Randomized Trial).40 Thus, the established link between procedural volumes and quality outcomes persists despite the advent of coronary stenting and improvements in adjunctive pharmacotherapies. Finally, mortality was reduced among patients with non-STEMI ACS who were initially treated at centers with cardiac surgical capability versus those treated at centers without such capability.41

Adherence to Practice Guidelines

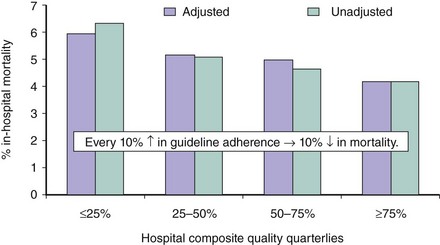

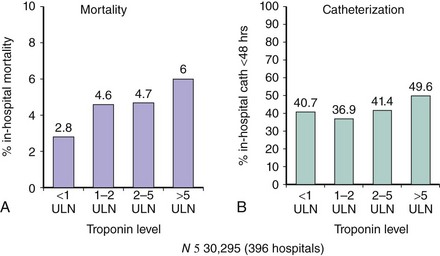

The process of care as measured by ACC/AHA guideline adherence has been linked to both in-hospital and late (6–12 month) survival following presentation of ACS.42,43 An analysis of hospital composite guideline adherence quartiles demonstrated an inverse relationship between the adherence to guideline-compliant care and the risk adjusted in-hospital mortality rate.25 For every 10% increase in guideline adherence, a 10% relative reduction in in-hospital mortality was observed (Fig. 36-1).25 This observation supports the central hypothesis of hospital quality improvement—that better adherence with evidence-based care practices will result in better outcomes for patients.44 The current system of nonregionalized care has been suboptimal in promoting and achieving guideline adherence, even in the case of those ACS patients who present with “high-risk” indicators.45 For example, only 33.8% and 44.2% of patients with elevated serum troponin levels in the CRUSADE (Can Rapid Risk Stratification of Unstable angina patients Suppress Adverse outcomes with Early implementation of the ACC/AHA guidelines) registry received early (<24 hours) GP IIb/IIa inhibition or early (<48 hours) cardiac catheterization, respectively.46 Similarly, although a direct correlation exists between the presence and magnitude of serum troponin elevation and in-hospital mortality, no correlation was observed between troponin levels and the performance of early (<48 hours) coronary angiography (Fig. 36-2), which has a class I ACC/AHA guideline recommendation for patients with NSTEACS with “high-risk” indicators (including elevated troponin).46 Both compliance with clinical practice guidelines and the ability to monitor or audit adherence to guidelines appear to be enhanced in higher-volume, regional programs.43,47 Adherence to guidelines was improved following establishment of an integrated, regional program for ACS care and was highest among the cohort of patients who received revascularization through PCI.48 Finally, guideline-adherent care of patients without STEMI was significantly greater in centers with cardiac surgical capabilities compared with those without those capabilities.41 Lower-volume, small community hospitals are unlikely to allocate their capital resources and personnel to adequately track, collate, and report clinical outcomes or process measures (guideline compliance). Certainly, from the perspectives of national and regional payers and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, monitoring and auditing data derived from multiple small hospitals versus those from fewer, larger networked systems have different levels of complexity. Indeed, in a recent survey commissioned by the AHA, only slightly more than half the hospitals queried were systematically tracking times to STEMI treatment (“door-to-needle” or “door-to-balloon” times), infection rates, re-admission or stroke rates (to 30 days after the procedure), recurrent MI, or mortality following either PCI or coronary bypass surgery.16 This observation is made more meaningful by the fact that multiple national initiatives such as Get with the Guidelines, the Cardiac Hospitalization Atherosclerosis Management (CHAMPS), the Guidelines Applied to Practice (GAP) project, the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI), and the CRUSADE (ACTION) registry have recently placed emphasis on system quality through systematic measurement of both care processes and clinical outcomes.9 The positive impact of these programs may be reflected in increased compliance with guidelines for early (≤24 hours) as well as predischarge medical therapies, in addition to the use of diagnostic angiography and revascularization.41 Similarly, the door-to-balloon (D2B) alliance, initiated in November 2006, has resulted in increased use of recommended strategies for process improvement as well as a greater portion of patients being treated within the recommendations of the guidelines.49

Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Centers without On-Site Cardiac Surgical Facilities

The current trend toward the proliferation of “PCI centers” which lack on-site cardiac surgical facilities for the performance of primary PCI in STEMI may be associated with suboptimal clinical outcomes. In an analysis of 625,854 Medicare patients who underwent PCI, in-hospital and 30-day mortality was significantly increased in those centers without on-site cardiac surgical facilities and was primarily confined to hospitals performing a low number (≤50) of PCI procedures in Medicare patients.50 Even in the context of a completely integrated community hospital–tertiary hospital system, the performance of primary PCI without on-site cardiac surgical facilities was associated with a trend toward increased hospital mortality compared with primary PCI performed at the tertiary center despite exclusion of the sickest patients (with refractory cardiogenic shock or ventricular arrhythmias) from PCI at the community center.51 Although single-center studies have reported excellent outcomes in patients undergoing primary PCI at hospitals without on-site cardiac surgical facilities, the one randomized trial that compared fibrinolysis to primary PCI at hospitals without surgery on-site was flawed by an inadequate sample size and by a majority of patients enrolled at a single site.52,53 More recently, large registry data suggested a similar risk for mortality following both primary PCI and nonprimary PCI performed at hospitals with versus without cardiac surgical facilities.39 Nonetheless, a significant mortality benefit following primary PCI in nonsurgical centers was achieved only by those institutions in the highest tertile of procedural volumes.40 Furthermore, the requirement for repeat revascularization appears to be increased at both 30 days and 1 year following primary PCI at hospitals without on-site cardiac surgical facilities.54 On the basis of these and other data, the current ACC/AHA guidelines for the performance of PCI designate a class III (practice may be harmful and is not recommended) indication for elective PCI and a class IIb (usefulness is less well established by evidence or opinion) for primary PCI in hospitals without on-site cardiac surgical facilities and point out the need for additional evidence base.38

Limited Medical Resources

The current trend toward the proliferation of small “heart centers” supposedly for patient convenience is counter to the well-established link between higher procedural volumes and better clinical outcomes; in addition, this taxes the already critically limited resource pools, including specialized nurses and subspecialty-trained physician–providers.55 Patients with more complex cardiovascular diseases (congestive heart failure [CHF], acute myocardial infarction [AMI]) fare better with care from subspecialty physicians (cardiologists) compared with care provided by generalists.8,9,56 One strategy for dealing with the mismatch between the emerging evidence in favor of an interventional (catheter-based) approach to the treatment of ACS and the current availability of such care is to establish regionalized centers for ACS care.8,9,23,57 Such centers would provide state-of-the-art radiographic equipment, a broad array of interventional supplies, and an experienced ancillary staff. Both subspecialty nurses and trained cardiologists are in limited supply.55,58,59 The proliferation of small “heart centers” that focus on PCI, with duplication of services, further taxes the limited resource pools and undermines the ability of established tertiary care centers to provide quality care. Indeed, the development of more PCI programs, particularly those without on-site cardiac surgical facilities, appears unnecessary in the context that the majority (>80%) of the adult U.S. population lives within a 60 minute commute to an existing PCI center.60 In fact, a recent study indicated that the expansion of PCI-capable hospitals was generally confined to urban and suburban regions and that this had a limited effect on increasing patient access to such care.61

Benefit of Catheter-Based Therapy for Acute Coronary Syndrome

Benefit of Catheter-Based Therapy for Acute Coronary Syndrome

ST Elevation Myocardial Infarction

The current ACC/AHA guidelines for the treatment of STEMI promotes reperfusion therapy (both fibrinolysis and PCI), with the choice of strategy based on resource availability and the anticipated time course for treatment implementation.62 The relative advantage of PCI versus fibrinolytic therapy depends on several factors. First, as primary PCI entails an obligate delay for implementation (versus fibrinolysis), the relative advantage of PCI depends on the relative delay to definitive treatment (balloon inflation). Pooled analyses of multiple randomized controlled clinical trials suggest that the survival advantage in favor of PCI is inversely proportional to the relative delay in PCI implementation and that the advantage may be lost if the PCI-related delay (door-to-balloon minus door-to-needle time) exceeds 60 to 110 minutes.63,64 Differences between these analyses may be explained by differences in patient risk profile. Indeed, a survival advantage in favor of PCI is evident only when the risk of death at 30 days following fibrinolytic therapy exceeds approximately 4%.65 Longer relative delays may still be associated with a PCI-related survival advantage in those patients at highest risk for death following fibrinolysis.66 Thus, accurate risk assessment should be part of any STEMI treatment triage algorithm. The relative survival advantage of PCI versus fibrinolysis is also dependent on the case volume experience of both the operator (cardiologist) and the hospital facility.

As noted previously, the best clinical outcomes and the greatest relative advantage of PCI are obtained by the highest-volume operators and institutions.67 The link between case volume and optimal outcomes has been established both for physician operators and hospitals and is evident with or without the availability of on-site cardiac surgical facilities.31,40,67 Transport to a center capable of performing PCI yields superior clinical outcomes compared with on-site (community hospital) fibrinolytic therapy when the randomization (treatment decision) to balloon time approximates 90 to 120 minutes.68 Importantly, no adverse outcomes related to patient transport have been observed in these analyses. Despite the observation that the vast majority (>80%) of individuals in the United States who experienced STEMI in the year 2000 lived within a 60-minute commute to an established PCI center, more recent data regarding patients who first present with STEMI to a community hospital (non-PCI facility) and are subsequently transported to a PCI facility demonstrate excessive delays to definitive treatment.60,69,70 Indeed, initial presentation to a non-PCI center has been identified as a major determinant of prolonged door-to-balloon times and reflects the lack of a well-defined integrated system with protocol-driven algorithms for care and dedicated transport facilities.71

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree