Notwithstanding improvements and changes in surgical and anesthetic techniques, the morbidity and mortality as a result of stroke and myocardial infarction following carotid endarterectomy (CEA) have remained constant since the 1990s at 3% to 5% in reported series. Surgical and anesthetic techniques are still, therefore, constantly under scrutiny to reduce these factors in an operation that is preventive rather than curative.

Many potential methods of providing anesthesia for CEA exist, including general anesthesia, local infiltration, cervical epidural anesthesia, and regional techniques such as deep, superficial, or intermediate cervical plexus blocks. Early nonrandomized studies suggested a lower incidence of cardiovascular and neurologic complications with local anesthesia, which was the stimulus for a large multicenter randomized, controlled trial.

The GALA trial was set up to answer this important question. It compared general anesthesia and local anesthesia for CEA in 3526 patients with symptomatic or asymptomatic carotid stenosis at 95 institutions in 24 countries. Subjects were randomly assigned to general anesthesia (n = 1753) or local anesthesia (n = 1773). A primary outcome (stroke, myocardial infarction, or death) occurred in 84 (4.8%) patients assigned to surgery under general anesthesia and 80 (4.5%) of those under local anesthesia; three events per 1000 treated patients were prevented with local anesthesia (95% confidence interval [CI], −11–17; relative risk reduction [RRR], 0.94 [95% CI, 0.70–1.27]).

Although GALA was the largest randomized trial of any anesthetic technique, it was still underpowered to detect a difference in mortality or stroke. Any technique for regional anesthesia or general anesthesia was permitted, which could therefore have diluted potential differences between the groups (i.e., introduced a type II statistical error). In addition, there were suggestions that there had been entry bias: Some patients were deemed unfit to undergo general anesthesia and therefore were not randomized in the trial; they subsequently received local anesthesia because some perceived it to be safer. Finally, a significant number of patients randomized to local anesthesia actually received general anesthesia but under intention to treat were analyzed with the local anesthesia group.

Overall, the GALA trial results were nonconclusive and have not therefore prevented surgeons and anesthetists from continuing their personal views concerning the advantages of one technique over the other. Whether or not there are differences in outcome between local and general anesthesia, there are certainly fundamental differences between them in terms of the way the operation proceeds and also in the patient’s hemodynamic profile during the operation.

The principal concern during CEA remains protection of the brain during carotid cross-clamping. For patients under general anesthesia, most surgeons use one or more techniques to detect inadequate cerebral perfusion, including carotid artery stump pressure measurement, electroencephalography (EEG), somatosensory evoked potentials, cerebral oximetry, or transcranial Doppler of the middle cerebral artery. Inadequate cerebral perfusion is an indication to insert a carotid artery shunt. Thus during general anesthesia, some surgeons use a shunt in all patients or request that the blood pressure be augmented pharmacologically to maintain cerebral blood flow. However, under regional anesthesia, the conscious patient provides a very sensitive and specific, albeit indirect, monitor of adequate cerebral perfusion. CEA is one of the few operations with such an appropriate monitor of the patient’s well-being. The GALA trial did show a clear difference in the incidence of shunting (14% local anesthesia vs. 43% general anesthesia).

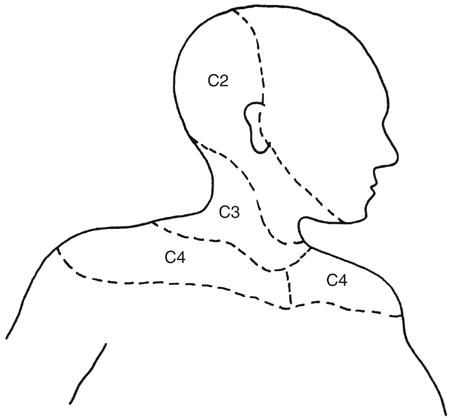

CEA under regional anesthesia requires block of the cervical nerves C2 to C4 (Figure 1). It is possible to achieve this using local infiltration, but it is more appropriate to use a regional technique. Cervical epidural anesthesia is infrequently used in the United Kingdom and United States, although there are large case series reporting its use in patients undergoing CEA elsewhere, particularly in France. Proponents cite the simplicity and success of the technique; however, because all cervical and upper thoracic nerve roots bilaterally are affected, there is significant associated morbidity, including a high incidence of hypotension and bradycardia, respiratory failure requiring intubation in 1%, dural puncture in 0.5%, and bloody tap in 2%. Additionally, placement of a cervical epidural in an elderly patient in the sitting position using the hanging-drop technique is potentially quite difficult and unnerving for the anesthesiologist.

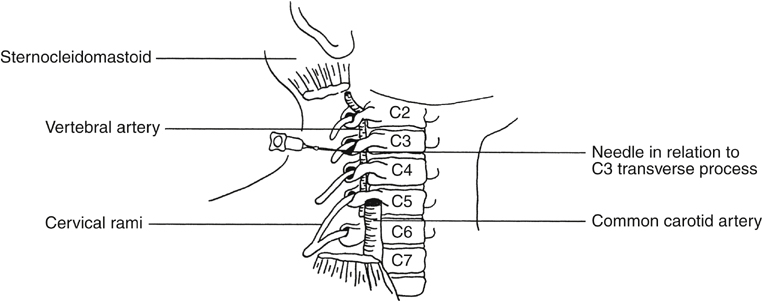

Cervical plexus block is straightforward to perform. It affects unilateral nerve roots only, has fewer cardiovascular side effects associated with it, and is probably a safer alternative. There are several possible alternatives, including deep, intermediate, and superficial block. The classic deep cervical plexus block may be performed using the modified single-injection technique of Winnie and colleagues at the level of C3 (Figure 2). The patient lies supine, slightly sitting up, with the head turned to the opposite side. The skin is disinfected with chlorhexidine in alcohol. The cervical transverse processes are palpated manually approximately 1 cm posterior to the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid. The third cervical transverse process is located by counting up from the sixth, which is at the level of the cricoid cartilage. After intradermal infiltration of 0.25 mL of 1% lidocaine at the level of the C3 transverse process, a 1-inch 25-gauge needle is introduced at right angles to the skin, aiming slightly caudal to avoid intrathecal injection. After location of the transverse process 1 to 2 cm from the skin or after the patient reports paresthesia in the distribution of the cervical plexus (see Figure 1), 20 mL of 0.375% plain bupivacaine is injected using an immobile needle technique.